Tory leadership contestant Rory Stewart has suggested solving Brexit with a citizens’ assembly, but what might it entail? CONOR FARRINGTON says, with the absence of political leadership, there needs to be a creative solution.

British politics is in crisis mode. British politics, in fact, has been continuously in crisis mode since 23rd June 2016, when 51.9% of those who turned out voted to leave the European Union. In purely philosophical terms that choice was meaningless, since (as Baroness O’Neill might put it) you can’t properly agree to something when that something isn’t well defined. This isn’t just an academic wrangle: it’s precisely because the command to leave can be interpreted in so many ways that we’re still trying to pick one that sticks. All the available choices are unpalatable to someone in one way or other, and each new round of proposals only seems to deepen the gaping divisions that characterise post-referendum Britain. In Westminster, meanwhile, the only thing the House of Commons can agree on is the need to avoid crashing out with an expensive and regressive no deal; but given the recent European election results and the startling YouGov poll showing that most Tories would prioritise Brexit over maintaining the party and even the Union, there will now be considerable pressure on the next Conservative leader to undermine Nigel Farage by embracing precisely that option. In other words, our politicians seem completely unable to sort out the mess they themselves created. (It was of course a different Conservative leader, David Cameron, running scared of Farage on a different occasion, who really kicked things off; but the political class tends to get lumped together at times like this.)

When crisis point is reached and solutions seem utterly out of reach, it’s tempting to yearn for a political mastermind to come along and solve all the riddles for us. Stephen Glover, for example, recently claimed in the Daily Mail that we ‘need a political genius to burst Farage’s bubble or a Corbyn-led Marxist government is on the cards.’ Sky’s Lewis Goodall was still more explicit: ‘In the Tories’ darkest hour, they need a Churchill.’ I succumbed to a similar temptation last year, ending my Times Literary Supplement review of Andrew Adonis and Will Hutton’s Saving Britain by calling for ‘new Attlees and Churchills… to supplant Corbyn and May.’

The temptation exists because it really is the case that Labour would benefit immensely from the weight of intellect and principle that a contemporary Clement Attlee could bring to bear on Theresa May and colleagues, just as a modern-day Churchill, appropriately shorn of outdated attitudes, would with all his fervour and oratorical brilliance unite the country at last behind a decisive and enterprising strategy. (Given Churchill’s celebrated pro-European leanings, which do not seem to have reached the ears of some on the right, this would almost certainly be a Remain strategy.)

The problem is that no such political heavyweights are to hand. Indeed, no such heavyweights are even in sight upon the horizon. Here is Lewis Goodall again, reflecting on the contest for the Conservative leadership and paraphrasing Churchill’s ‘Finest Hour’ speech: ‘never in the field of political conflict were so many candidates found so wanting; [never were there] so many with so much to say, to so little effect.’ Yet while Conservative weakness, division, and intellectual bankruptcy is to the fore, Labour can hardly claim to be in much better estate. Rocked by claims of anti-Semitism and sexual harassment within the party, and embarrassed by an extremely poor showing in the European elections, Labour’s main response appeared to be the expulsion of Alastair Campbell for voting Lib Dem. In 2017, in a masterpiece of understatement, Gaby Hinsliff stated that politicians aren’t as good as they used to be: ‘You don’t look at them and think, “This is a generation of total A-listers.”‘ It seems fair to suggest that little has changed since then.

In the absence of an actual political genius, perhaps we can imagine ourselves into the shoes of great politicians and channel their originality instead. Evangelical Christians often wear wristbands inscribed with WWJD: What would Jesus do? What if we had wristbands inscribed with WWWD – what would Winston do? Churchill is, of course, best known for uniting the British people against Nazi Germany during World War Two, and for this reason a great deal of political energy on the right has been expended on anachronistic rhetoric that evokes the spirit of the Blitz, with Britain standing alone against a threatening European adversary. Churchill’s own political inspiration, however, lay much further back in what he called the ‘old glittering days’ of the 1880s and 90s, when he imbibed the spirit of Tory democracy from his father, Lord Randolph Churchill. And the motto of Lord Randolph’s Tory democracy was simple: Trust the People.

In one sense, this kind of generous impulse is behind Conservative leadership contender Rory Stewart’s recent call for a Brexit-focused citizens’ assembly – a series of invitation-only meetings in which as many as five hundred citizens, chosen to represent the public along multiple dimensions, would undertake communal learning and deliberation with the aim of making recommendations to parliament. (A similar approach has just been adopted by the Scottish government, to reflect on the future of the country.) Inspired by the effective use of a citizens’ assembly in the recent Irish abortion debate, Stewart stated: ‘I have a lot of confidence that we are one of the most educated and articulate populations on Earth and that if we had a citizen assembly they would be able to do what parliament has failed to do: step back, put party politics aside and look at a sensible resolution to this.’ Putting aside Stewart’s rather contentious claims about education – in 2017 the Independent reported that Britain has the lowest teenage literacy rate in the OECD – the idea of a citizens’ assembly is one of the very few with the potential to make a transformative breakthrough on the current Brexit impasse.

Some moderates endorse this approach as a way to put Brexit ‘back to the people’ without requiring a second and (potentially) yet more divisive referendum. The resulting consensus, or compromise, could be seen as legitimate (it is argued) because assembly participants, benefiting from expert advice and time to deliberate, would be far more informed (and perhaps more reflective) than the vast majority of voters. But precisely for this reason it’s hard to see why the public would take much interest in the proceedings, any more than the average person watches BBC Parliament or reads select committee reports. If the 51.9% voted for Brexit because they’re suspicious of ‘elites’, impatient with complicated arguments, and bored with politics as an endless continuation of the once-vaunted ‘Westminster consensus’, then approaches like citizen assemblies may struggle to get their pulses racing.

Parliament and government, meanwhile, could discount the proceedings since they would be unrepresentative of actual public opinion, which is usually less well-informed. Certainly, politicians paid remarkably little attention to the conclusions of the citizens’ assembly on Brexit run by Involve in 2017, which, among other conclusions, ruled out no deal. citizen assemblies, from one point of view, offer an alluring retreat from the chaos and viciousness of social media, protest marches, and 24/7 news reporting, an oasis of calm and judicious rationality. But it can be argued that retreating from the people – from the arenas and milieu in which the people live their daily lives – is hardly to trust the people.

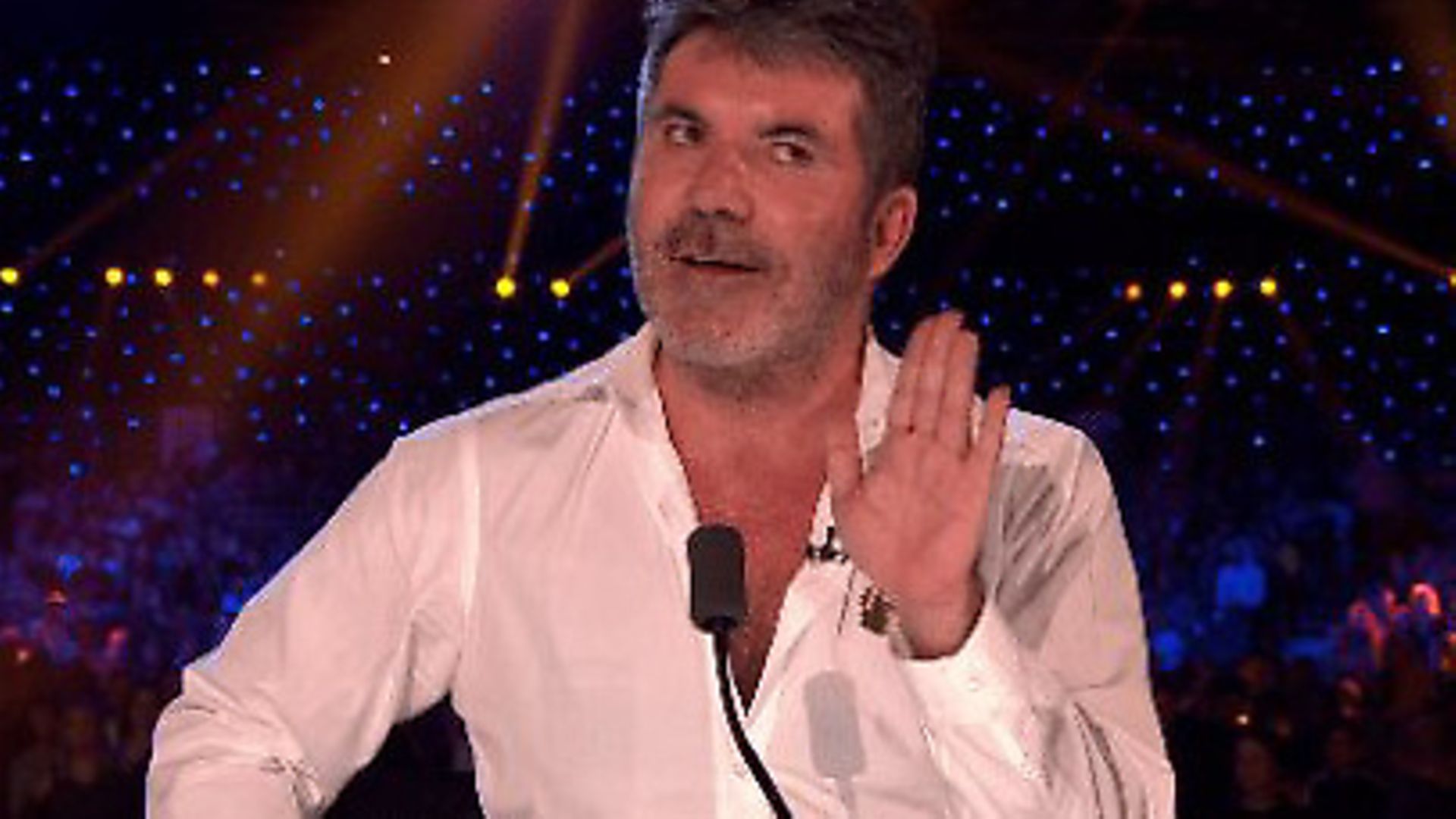

Perhaps one solution to this paradox is to embrace not just the people but the kind of entertainment that the people like to watch. Churchill always embraced new technology for political purposes, making radio and then television broadcasts with great aplomb. Is it too much to think he might also embrace reality TV, if the political circumstances demanded it? Despite fierce competition from streaming services, reality TV shows like The X Factor and Britain’s Got Talent still pull in large audiences, sometimes in excess of ten million viewers. Perhaps a Brexit citizens’ assembly could be run as a reality TV show, complete with nightly episodes featuring celebrity guests, public votes of various kinds via telephone and app, and alluring competitions, alongside the more serious business of expert and politician interviews, careful deliberation among a representative body of citizens, and the generation of a final set of assembly recommendations to parliament, government, and the country. I recently suggested the title The Brex Factor, but others could easily be imagined. (The Great British Take-Off? I’m British… Get Me Out of EU? Lovelorn Island?)

Adopting such an approach would not be without its challenges. The process would have to be independent of government and perhaps even of parliament, in order to avoid any suspicion of undue influence – politicians could still appear as invited guests and assembly interviewees, of course. Steps would need to be taken to avoid trolling of assembly participants, perhaps by preserving their anonymity altogether. To avoid suspicion of rubber-stamping, all options would have to be on the table: it is no use in stating at the outset, as Stewart has, that an assembly recommendation to Remain would be seen as merely advisory. (The referendum, too, was strictly speaking merely advisory.) And perhaps Stewart’s nominated compere, the Archbishop of Canterbury, might judiciously be replaced with Ant and Dec or Dermot O’Leary. If these and other challenges are met, it seems plausible that The Brex Factor could help to inform the public about the manifold and largely under-appreciated complexities surrounding Brexit, while also entertaining them and making politics interesting for a change. This alone could have a transformative impact on public perceptions of politics and politicians, currently less trusted than estate agents.

Before the referendum in 2016 Simon Cowell stated his belief that the people are always right: ‘I always trust the public to make the right decision.’ But he also went on to declare himself a Remainer: ‘I don’t think at this time – because it is a tricky time – you would want to be on your own on a tiny island.’ Perhaps there is now an opportunity for him to help reconcile these two perspectives, and at the same time transform assemblies – dismissed by Madeline Grant as a ‘wonkish gimmick’ – into a dramatic new kind of large-scale participatory democracy. In other words, perhaps Simon Cowell and his slick productions could succeed where countless politicians, pundits and experts have failed, and finally bring the country together in one way or another. In an age characterised by divisive echo-chambers and post-truth media, it would be a supreme irony if reality TV should end up taking the place of political leadership. But in the absence of a bona fide political genius, maybe any kind of leadership will do.

– Conor Farrington is a Senior Research Associate at the University of Cambridge and an Associate at Hughes Hall Cambridge.