They say you shouldn’t meet your heroes. Zelda Perkins not only met hers, she produced the musical he staged in his dying days. She gives a first hand account.

“I know nothing about producing theatre,” I said. I was talking to the theatre impresario and film producer, Robert Fox. And I needed a job. He had suggested that I might become his associate producer.

I didn’t feel that the theatre studies module of my degree many moons before would qualify me but, it turned out, my years working for (the now disgraced) Harvey Weinstein and Miramax, not to mention my enthusiasm for the plays of David Hare, did the trick.

And the first project I was given to manage was Hare’s Skylight at the Wyndham’s Theatre in the West End, starring Bill Nighy and Carey Mulligan. Producing it, Robert had predicted, would be a much easier and more joyful experience than producing a film. And so began a very happy partnership that continues to this day.

When I joined him, Robert was engrossed in a big Andrew Lloyd Webber musical called Stephen Ward. He needed someone to take some of the load of the plethora of exciting projects he had on his slate. These ranged, he told me, from a new Martin McDonagh play, something with Nile Rodgers of Chic, another with Hugh Jackman, a new television series about the Royal Family by Peter Morgan, a film script and, oh, potentially a musical with David Bowie.

Wait. David Bowie? He paused. It’s in development, he said, but before that we need to cast someone to play the Queen in the London revival of The Audience as Helen Mirren was moving to play Her Majesty on Broadway.

But I was still stuck on Bowie.

The world of theatre production was to be a happy discovery for me. After my bruising experience with Weinstein (that’s another story) it was a revelation to work in an industry where the writer, director, set designer and other creatives were treated as artists. Producers in theatre respected all their work and did not try to change endings to suit test audiences or tell a director how to do his or her job.

There must be at least five different types of film producer plus more production managers and associates and executives. They wield budgets of millions and crews of hundreds. In a theatre, the producer has a smaller crew and a finite run on the stage but is directly responsible for all aspects of a production, from budget to casting to renting the theatre space. I loved it.

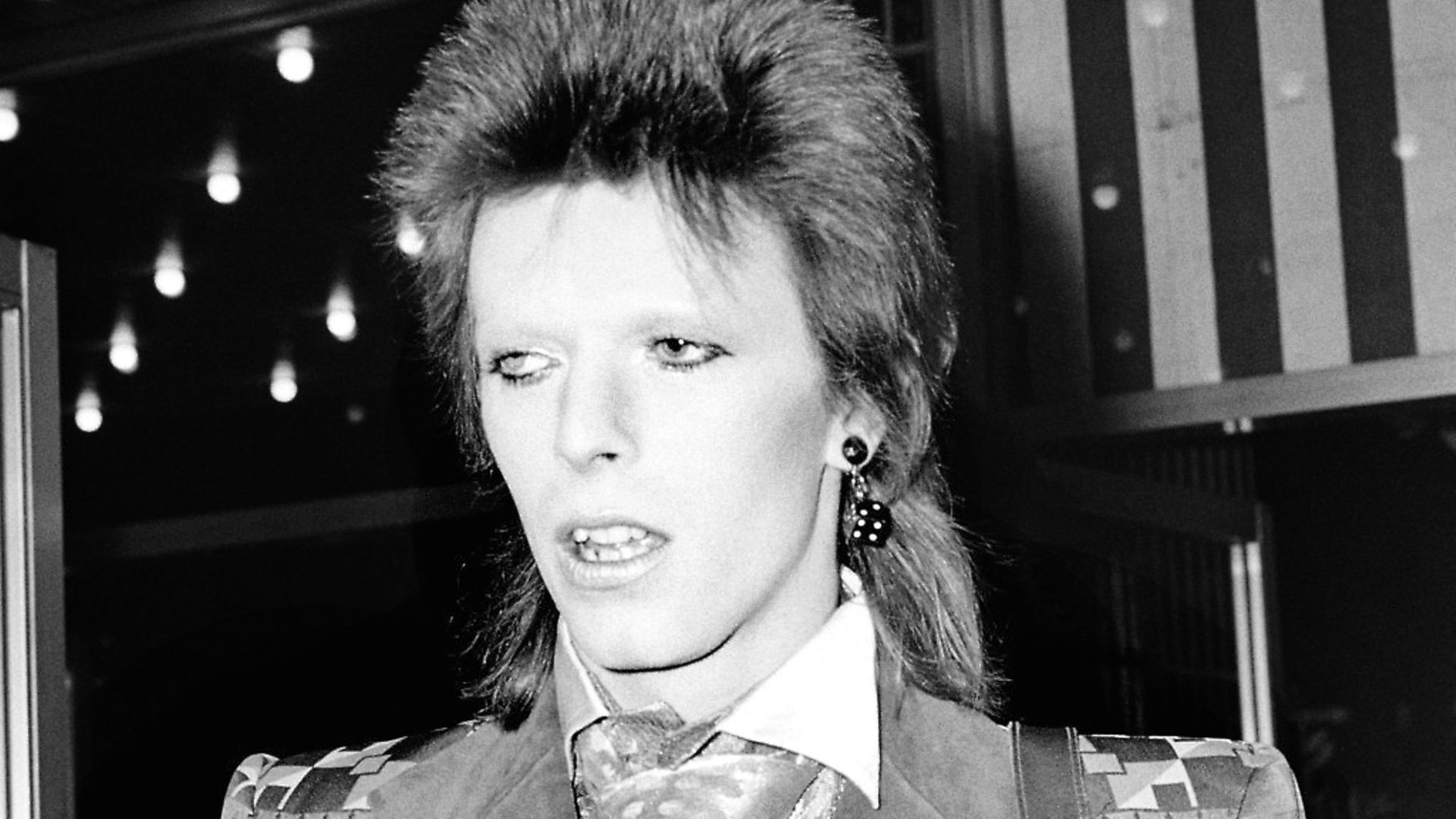

In 2013 I began to get involved with the Bowie project. It was made clear that I would be unlikely to have direct contact with David himself. I was both thrilled and secretly relieved. For me, as for many people, he was an awe-inspiring figure, one of the great artists of our time and provider of the soundtrack to my life.

Working in the film industry had introduced me to many of my idols and, almost without exception, I’d been disappointed every time. The thought that David Bowie might be the same was too much to bear. Supposing he had halitosis? Or was a mean-spirited egotist? Or frankly just an ordinary human? I was more than content not to meet him.

It turned out that in 2005 David had given Robert a copy of the Walter Tevis novel, The Man Who Fell to Earth. This was the book on which Nicolas Roeg had based his 1976 film of the same name, starring Bowie. His appearance in the film had become an enormously important part of the Bowie iconography and reinforced his “alien” reputation. Images from the film adorned the covers of his albums Station to Station (1976) and Low (1977), not to mention countless magazine covers and posters. There was no explanation for this precious gift, just an inscription in the flyleaf:

Robert, ‘Im not a human being at all’ (Thomas Jerome Newton)

(SSSHHH!! David Bowie)

David

2005

Now, eight years later, David told Robert he wanted to make a musical called Lazarus about the character (Thomas Jerome Newton) he had played in the film – an alien trapped on Earth.

Robert had then introduced David to Enda Walsh, a hugely talented Irish writer, and work began on the outline of the show. Suddenly, in 2014, the project was fast-tracked at David’s behest.

I thought no more – then – of this sudden acceleration; such things are common in the creative industry. We arranged for David to meet Ivo van Hove, the avant garde Belgian director whose production of Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge had wildly impressed London critics and audiences. It had especially hit a note with Robert when thinking of a pairing for the Bowie project, and once David’s collaborator Henry Hey was added as musical director, the team was complete.

We set up a workshop in New York, where Bowie lived, to see how the material and music we had at this point worked with actors. This was not as easy as usual to arrange because we had been told not to give any details about the project to agents: No script, no music, no clue as to who had originated the project. The only thing we could say was that “a world-famous composer/performer” was involved. This made it extremely difficult to attract the sort of cast we wanted but all our instructions from the Bowie camp were to keep utmost secrecy at all times.

I was allowed contact with David’s business manager, Bill Zysblat, in New York but still only Robert could communicate directly with David, or Coco Schwab – the woman who had been at his side since the early 1970s and who was known to guard him fiercely. Coco and David often seemed to have one voice. Robert’s creative questions to David were often answered by Coco in the plural: “We think”, “we would like”.

Gradually, and despite the mystery, we assembled a cast to workshop the material and see what we had. Each actor was asked to sign a non-disclosure agreement before being given sight of the rough script and song-list for the day.

In December 2014 we all gathered in a large rehearsal space on 42nd Street. The room was electric with anticipation: Henry Hey at the piano, a circle of chairs for the actors, and a small group of those of us involved thus far, watching and waiting for a legend to appear among us. Beside the piano was a chair for Ivo and a small camera on a large tripod. Introductions were made but there was still no sign of Bowie.

Only when the time came for the actors to begin did the message come: David was ill (flu, we were told) but he would be watching from home on that camera. It blinked green when he was viewing, we learnt, so no one could take their eyes off it.

Henry had an earpiece through which he was communicating with David but otherwise there was no tangible sign of his presence, apart from that camera. It was a fittingly surreal start to a production that eventually grew, according to the Rolling Stone critic, into “a surrealistic tour de force”.

What only four people in that room knew (and I wasn’t one of them) was that David’s “flu” was, in fact, cancer.

When the production came to rehearsals, David attended as often as possible in person. He wanted the show to be produced close to him, so the off-Broadway New York Theatre Workshop (noted for its productions of new and challenging works) was the natural choice to co-produce the project. They had close ties with the writer and director and the theatre was in walking distance from Bowie’s East Village home.

Reports from Ivo and the cast all told of David’s enthusiasm and creative generosity. He put everyone at ease as they sang his iconic songs to him. David wanted each cast member to own the songs, to interpret them as they wished, to live them in their experience. This generosity and collaborative nature had shown itself early in the process when David had asked Enda to choose the songs he wanted for the show. Enda did not make the obvious choices and David, with the help of Henry, then carefully rearranged the 13 songs for the stage. He also wrote four new songs specifically for the production, one of them being the title track Lazarus, which was later to become his first US top-40 single since the 1980s, streamed by nearly nine million people in the week of its release.

Marketing a musical show without being able to give any information about what it would be about or what music it would contain was a challenge. We had strict instructions from David that we should not give an outline of the story or music to the press. All we could say was that it took its inspiration from The Man Who Fell To Earth. He wanted people to come to Lazarus without preconceptions. David made it clear to us that he did not want the production or the narrative to be explained: As with the cast taking ownership of his songs, he wanted people to have their own individual experience of what they saw on stage and how it made them feel, no matter how confused they may be.

People at the New York Theatre Workshop were nervous about this strategy and I didn’t blame them. Even the artwork for the production was mysterious: a moody evening East Village skyline. David had been presented with several other ideas: Major Tom-style space helmets, rockets in huge television screens – all images that related to Bowie and to the content of the show. But he emphatically chose the most obscure image that revealed almost nothing.

He would make no statement for the press, declined every request for an interview and would do no publicity but when tickets went on sale in early October they sold out in hours. Theatre doesn’t work like rock’n’roll; it is virtually unheard of for an entire run to sell out hours after going on sale. Resale sites were soon asking for $1,000 a ticket.

It didn’t hurt that our Newton was Michael C Hall, a star in his own right having won a Golden Globe for his performance in the television series, Dexter. And the show would run for only a few weeks. But there was no doubt whose name was selling the tickets.

As the dress rehearsal approached Robert was suddenly taken gravely ill, so I had to go to New York without him. Arriving late in a taxi straight from the airport, I was frazzled and had a headache, my nerves only slightly calmed by Coco informing me that she and David would not be there.

After brief hellos with our co-producers from the New York Theatre Workshop, I took my seat in the centre of the auditorium and made sure there was no one to my left or right. I wanted to watch undisturbed by the technical staff or the few invited guests. I had notes to write. I would not only have to relay my opinion to Robert later that night but immediately after the show, in Robert’s place, give my thoughts and suggestions on the production to the director, designer, sound, light and music heads of department. No one there knew this was my first foray into musical theatre.

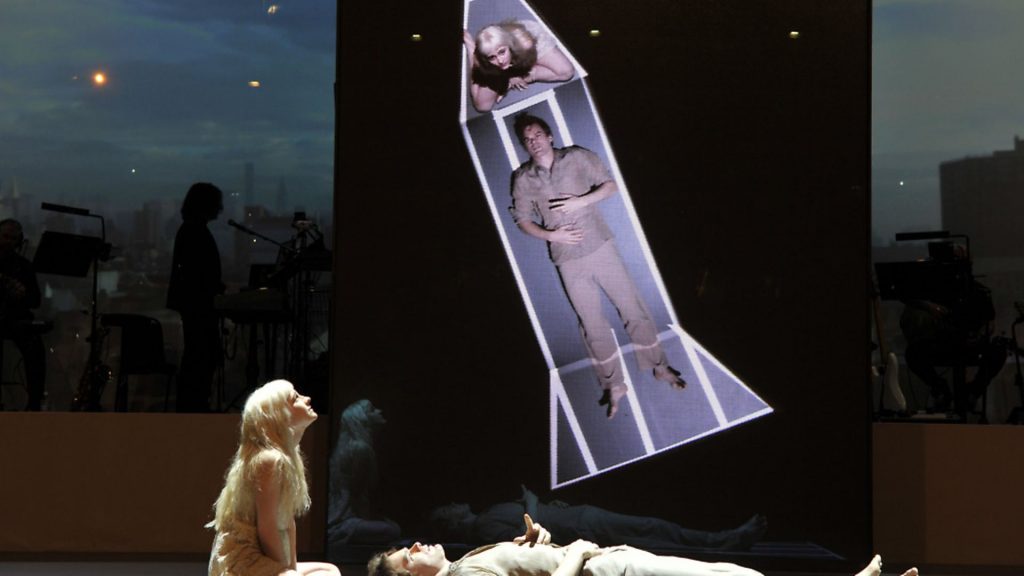

The lights went down and a story I thought I knew well began. What unfolded on stage, however, was unlike anything I had ever seen. It was raw, challenging, heartbreaking, confusing and deeply uncomfortable to watch. I sat mesmerised, feelings of euphoria and horror fighting for supremacy. This was a graphic, surreal and highly stylised production that tore furiously at the depths of loneliness and lost hope in a wild journey, peopled with characters whose existence in reality or fantasy were difficult to distinguish.

It was hard to describe, featuring as it did balloon-popping, milk-sliding, serial killing, copious amounts of gin and blood with replays of the live action appearing on a giant television screen. All this might be enough to discombobulate the regular theatre-goer and David’s songs coming to life in new ways might confuse those expecting something more familiar. All this, I later discovered, was to Bowie’s absolute design and delight.

When at last the lights came up, I rushed to the loo to get my mind straight and ready to talk to Ivo and the director of the New York Theatre Workshop. What could I say to everyone that would be honest, coherent but still encouraging?

As I returned to the foyer a small, grey-haired woman grabbed my arm. It was the elusive Coco. “You must speak to David,” she said, propelling me back into the auditorium. She and David had been there to watch the show after all. My heart fell to the floor.

I was pushed towards him, protesting to Coco as I went that David should speak to Ivo and the other creatives first. But David clambered over the two rows of seats separating us, pulled me into the aisle and enveloped me in an enormous hug. “Zelda,” he said. “We meet at last!”

He was wearing a baseball cap and an overcoat, though the room was warm, but there was no disguising his pallor and that he was struggling for breath. However, his eyes were ablaze and he immediately started talking excitedly about what we had just witnessed. He wanted to know exactly what I thought. Did I like the new arrangements of his songs? What did I think of the choreography? Wasn’t it marvellously tangled and surprising? He was holding my hands (or was I holding his?) and I found I couldn’t break his gaze, or not be infected by his delight. My inner voice of doubt and commercial worry was immediately silenced. I had been reminded that the true artist does not fear the viewer’s gaze.

David Bowie was officially the most delicious smelling man on Earth. I know this because of that hug. I didn’t shower that night and slept, smiling, with the intense, clean smell of him in my hair and on my pillow. Nothing about him had disappointed after all. But less than two months later he was gone for ever.

It was not until I saw him myself at that dress rehearsal that I saw the truth of the situation. He was ill. Terminally ill, as it turned out. Those around me seemed not to have seen it, or had chosen not to acknowledge it. Perhaps that was easily done. Perhaps that enormous enthusiasm, which seemed to light David from within, blinded those working with him to his gaunt appearance and laboured breathing. I find I can easily believe that.

And his work rate was astonishing. He may have been ill and coping with the treatment but he was not only helping create Lazarus, he was also working on his final album, the majestic Blackstar. In fact, the lead song for the theatre project became the second single and video released for Blackstar, poignantly – or perhaps purposefully – on David’s birthday, January 8. Two days later his death was announced.

While we had been in New York attending the start of rehearsals in 2015, he had been on set filming the Lazarus video. Strapped to a vertical hospital bed, made up as a dying man, his voice thin and breathy, he sang: “Look up here I’m in heaven, I’ve got scars that can’t be seen … I’m in danger, I’ve got nothing left to lose.”

How was it that none of us heard what he was so clearly saying?

The Blackstar and Lazarus videos and lyrics now seem so obviously stuffed with clues. Did no one hear or see these clues that were screaming through the songs and dialogue about the frailty of mortality – his own mortality?

The opening night for Lazarus was on December 7, 2015. David attended. The Thin White Duke made flesh took the curtain call with the cast to the surprise and delight of the audience. He took a last and extravagant bow on stage, laughing with unbridled joy and holding hands with the cast and the director of the musical he had for so long hoped to realise. It was his last public appearance.

On the morning his death was announced, the cast were scheduled to record the cast album of the show. Shell-shocked, they gathered in a recording studio and sang their grief out for Bowie – each song carrying a new resonance.

Critics reappraised their initial reviews of the show, which suddenly became more cohesive and coherent to them. A shrine of candles, flowers and pictures soon covered the pavement outside the theatre. The outpouring of grief from all around the world was a tidal wave, fuelled no doubt by the quiet dignity and purpose with which David had left.

To many it seemed almost stage-managed. David didn’t want explanations and it is not for me to try to explain his art but Lazarus and Blackstar now seem clearly works about his impending death. And as we keep discovering, a trail of clues and surprises was laid along the way. One of these, which makes my eyes prick even now, was the album cover of Blackstar. A month after the vinyl version of the album went on sale, it was discovered that if the sleeve was exposed to direct sunlight the black star graphic on the cover dispersed to reveal a galaxy of stars – a sweet and happy gift from beyond the grave. Jonathan Barnbrook, who designed Bowie’s album covers, including the cast album artwork and the Lazarus theatre programme, has since admitted that there are several hidden “easter eggs” still to be found.

But Lazarus did not end here for me. We brought the production to London but were not content that it should sit in a West End playhouse. It needed a venue that gave the audience the full experience of the seven-piece rock’n’roll band who were on stage throughout. Their sound had been so carefully curated by David and Henry to be as intense as any live rock concert it had to be heard in the right acoustic environment. In the end we built a huge and dramatic space, seating a thousand, near King’s Cross and the show gained the scale and volume that David wanted.

Each night the atmosphere in the bar before the show had the energy of a concert, or a one-off event. And each night the show reports detailed the visceral effect the production had on the audience. Tears, anger, outpourings of love and emotion on a scale astonishing to the staff. The critics, however, were divided.

As for me, I believe Lazarus is ahead of its time and will only continue to give more and more as time passes. More secrets revealed themselves each time I saw it and even after more than 20 viewings it had an overwhelming effect on me. Tears came always but I could never predict at which point. Laughter, too, and I left always a little wiser.

Bowie once said: “I’d like my death to be as interesting as my life has been.” Oh, how he succeeded.

– This story was first published by Tortoise, a different type of newsroom dedicated to a slower, wiser news. Try Tortoise for a month for free at www.tortoisemedia.com/activate/tneguest and use the code TNEGUEST