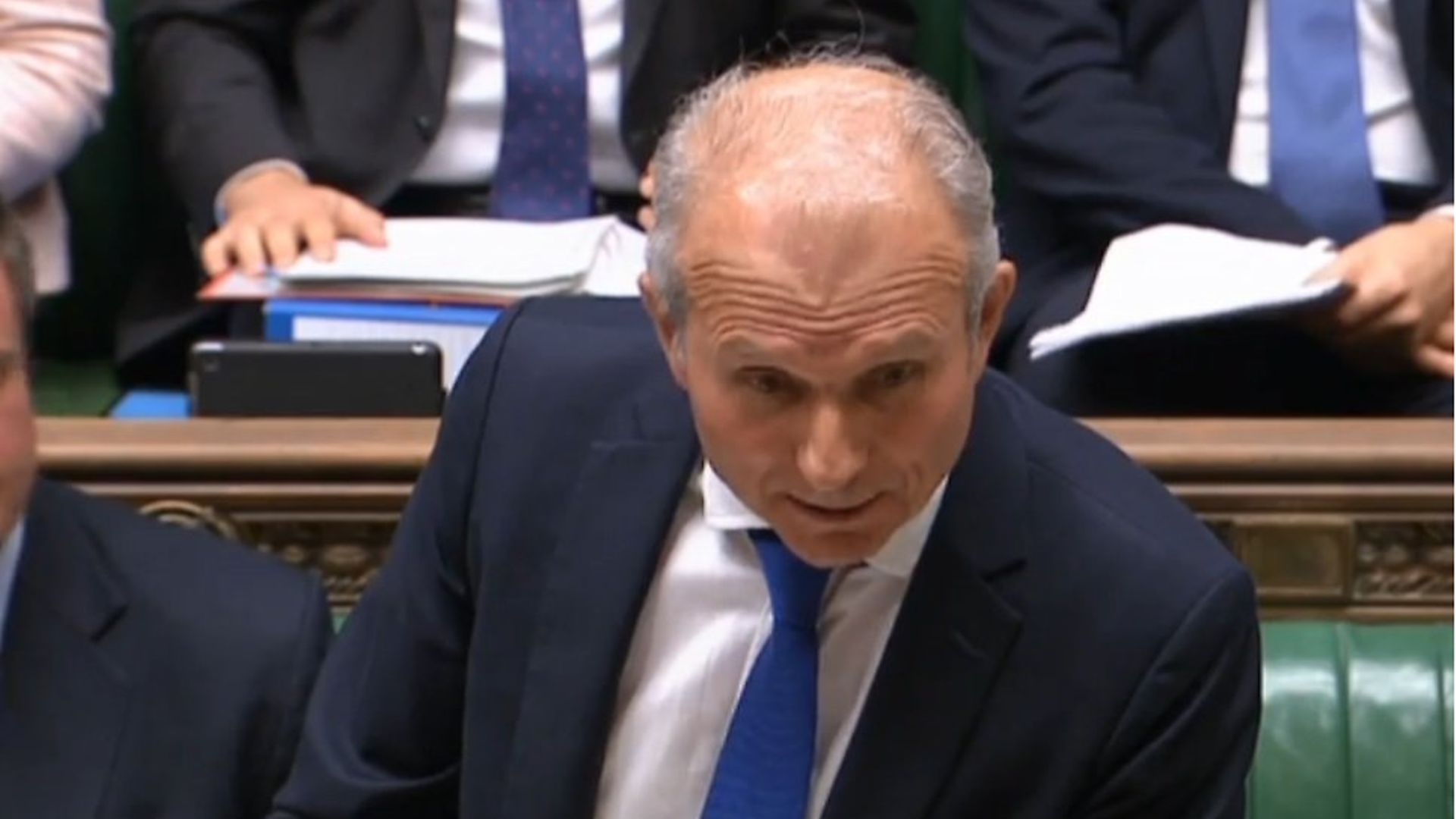

Former de facto deputy prime minister Sir David Lidington tells MATT WITHERS about how he will continue campaigning for the Conservatives to be a pro-European party.

The night before I speak to former de facto deputy prime minister Sir David Lidington, the organisation he chairs changed its name. Goodbye Conservative Group for Europe, hello Conservative European Forum!

This makes sense, I suggest, because the original sounded like Labour Group for Fox Hunting, or Liberal Democrat Group for First Past The Post: a bit niche.

He laughs. “Look, there’s always been a very strong pro-European element within the Conservative Party,” he says, saying 20% of Conservative voters in 2019 had been former Remain voters.

But the man who served as Theresa May’s deputy for 18 months is deadly serious. The organisation, under its original name, was formed to promote the UK’s entry into the EEC. Its leading members you’ll recognise: not just Lidington, but John Major, Ken Clarke, Michael Heseltine. But in 2016, they lost and, like the UK itself, are looking for a role.

“What I have said to our members is that we have to accept reality,” the 64-year-old tells me via Zoom from his home in Buckinghamshire.

“We have to accept that, however much we regret the decision, however much we think it was a mistake, that Brexit has happened. You don’t get any prizes in politics for going around telling the electorate that they made a dreadful result last time, they need to wake up and admit this.

“You have to deal with the situation now and the debate in the next five, 10 years or so is going to be about the kind of relationship that the United Kingdom and the European Union, both at national government level and at institutional level, make with each other.

“And what we will stand for and push for and advocate for is a close strategic partnership between the UK and the other European democracies. We will seek to provide a forum for discussing these matters in detail on things like decarbonisation, on the future of data and artificial intelligence, on financial services, on international trade, on foreign policy.”

As well as people on the centre-right of British politics, he says, it will work with businesses and those parties on the continent who should be the Tories’ partners, “most obviously the parties that are members of the European People’s Party, mainstream Christian democrat and conservative parties”. He doesn’t explicitly mention David Cameron taking the Conservatives out of the EPP to lead a new movement of Eurosceptics but does say “there are relationships which for obvious reasons have become bruised in the last four or five years.”

But I do wonder if that ship has sailed for the Conservatives. Surely the thing about Boris Johnson’s party, and specifically its most recent intake of MPs, is not only that it is hostile to Europe but explicitly defines itself by it?

“I think that you can exaggerate that,” argues Lidington, who stepped down from Parliament in 2019 having backed first Matt Hancock then Jeremy Hunt against Johnson for the leadership.

“The 2019 general election, and in the years immediately before, the Conservative Party was convulsed by the European issue. But that’s not where most of the public are. For the great majority of British voters the appeal of Boris Johnson’s slogan of ‘Get Brexit Done’ was not that it pointed to a particular outcome to the negotiations, but it held out the prospect of getting a wretched subject that most people were impatient with out of the headlines, off the front pages and the news bulletins.

“I also think you need to look both at what the Johnson government has done since it took office and at some of the language since the Trade and Cooperation Agreement was finalised. If you look at some of the key foreign policy decisions since Boris Johnson became prime minister, on Iran, on Israel-Palestine, on climate, despite all the pressure from Trump he’s actually chosen a policy which is pretty much aligned with the European position.

“You know, the British embassy in Israel is still in Tel Aviv, we didn’t recognise the settlements in the occupied territories, we stuck by the nuclear agreement with Iran.

“You also look at what he did when President Macron asked for a further British contribution in the Sahel. We had an increase in the UK contribution to the French-led counterterrorism effort in Chad and Mali.

“So the pattern there has actually been of somebody who, you know, while we’re having a big argument – this is in the middle of the most acrimonious at times divorce talks – the policy fundamentals were actually leading to an alignment with the European position.”

But he’s “not going to pretend this will happen overnight”, he says.

“There are bruises. And there will be aftershocks. You know, from what we saw last week with the row over the diplomatic status of the EU embassy in London to this week’s sort of bit of vaccine nationalism on both sides of the Channel, which is all a bit dispiriting. But that’s inevitable. An eruption is followed by aftershocks.

“But as time goes on people focus on the next challenges that we face. My view is that the strategic fundamentals of policy are so clearly pointing towards the UK and the EU working together that that is the direction in which we will start to move.”

He doesn’t think a viable rejoin movement is likely to become a feature of British politics in the next decade, arguing it is “off the agenda for the foreseeable future”.

“Certainly I think the task for the next five to 10 years is about building up a close strategic partnership with our friends and neighbours,” he says.

“I think the Liberal Democrats probably will campaign to rejoin – they’re hitting about five or six percent in the UK polls at the moment. I don’t think the Labour Party’s going to come near adopting that approach and the Conservative Party isn’t going to either.

“The people who talk about a campaign to rejoin are just misreading the mood amongst both British voters and amongst the 27.

“If you’re the 27… as I’ve observed, with each month, year that’s passed since the British referendum they have increasingly focused not on the UK and Brexit but on the things they need to decide as a community of 27. I was very struck when I read the German presidency document for the second six months of last year at how Brexit had a single mention. There was one paragraph on page 21 sandwiched by paragraphs on America and on China.

“I just don’t see this as being on the agenda for the foreseeable future.” (Although he concedes that “none of us know what the UK or European Union will look like in 15, 20 years’ time”.)

One question remains, though. This article, like every article about Lidington which will ever be written up to and including his obituary, refers to him as “de facto deputy prime minister”.

His actual job titles were Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office. Didn’t he ever buttonhole May, say he was working jolly hard and would like the title?

“I didn’t,” he laughs. “The truth is, I thought she had so much on her plate that, you know, a conversation about titles which might have been putting noses out of joint amongst other members of her cabinet was not the top priority.

“I did come to the view when I did that job… that I think that every prime minister should have a designated deputy who has the title of deputy prime minister and almost certainly that person has got to be in the Cabinet Office, because that is the functional centre, the operational HQ of government, of Whitehall.

“And certainly, particularly in the early stages, I would have been able to do more had I had that title. After two or three months my cabinet colleagues could see that that’s how I was functioning because they could see I had the access to the prime minister, I had the trust of the prime minister, the prime minister was delegating roles to me in chairing committees, in trying to broker deals between different members of the cabinet.

“If you had the title it just helps from the start. It’s a message to everybody from top to bottom in the whole British system of government.”

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk