ALASTAIR SMART on the long-overdue emergence of Pieter de Hooch from the smothering shadow of his most famous contemporary.

It’s easy to see why a new exhibition devoted to Dutch old master, Pieter de Hooch, is subtitled From the Shadow of Vermeer. The two men weren’t just peers but rivals, during the decade de Hooch spent in Vermeer’s home city of Delft in southern Holland.

That decade was the 1650s, when both were members of the Delft artists’ guild. In the centuries since, paintings by one have often been misattributed to the other. Such is the similarity between many of their pictures; such was the extent of their mutual influence.

In terms of popularity and renown, however, there’s really no comparison. Vermeer is a household name worldwide, an exhibition of whose at Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam museum earlier this decade broke UK attendance records for a show outside London.

De Hooch, by contrast, has fallen from grace pretty dramatically. Between his death in 1684 and the current show, he didn’t have a single, solo exhibition in his homeland.

Who exactly was Pieter de Hooch, then? What made him special? And how to explain his neglect for so long?

Born in Rotterdam in 1629, de Hooch was the son of a bricklayer and a midwife. Biographical information is patchy, though we know he moved to nearby Delft in his early twenties. The city at the time was flourishing, thanks to its butter and cloth industries – not to mention its establishment as one of the headquarters of the Dutch East India Company.

As so often in history, art followed money. Sensing sales and opportunity, a number of painters swiftly began settling in Delft, Carel Fabritius and Jan Steen to name but two. (Fabritius, a promising pupil of Rembrandt’s, best known for his painting The Goldfinch, would be tragically killed by a gunpowder explosion near his house in 1654.)

It’s estimated that around two-thirds of Delft’s homes in the mid-17th century contained paintings. The recent declaration of the Dutch Republic – and with it the end of rule by Catholic Spain – resulted in a sharp decline in religious imagery and rise in demand for secular subjects.

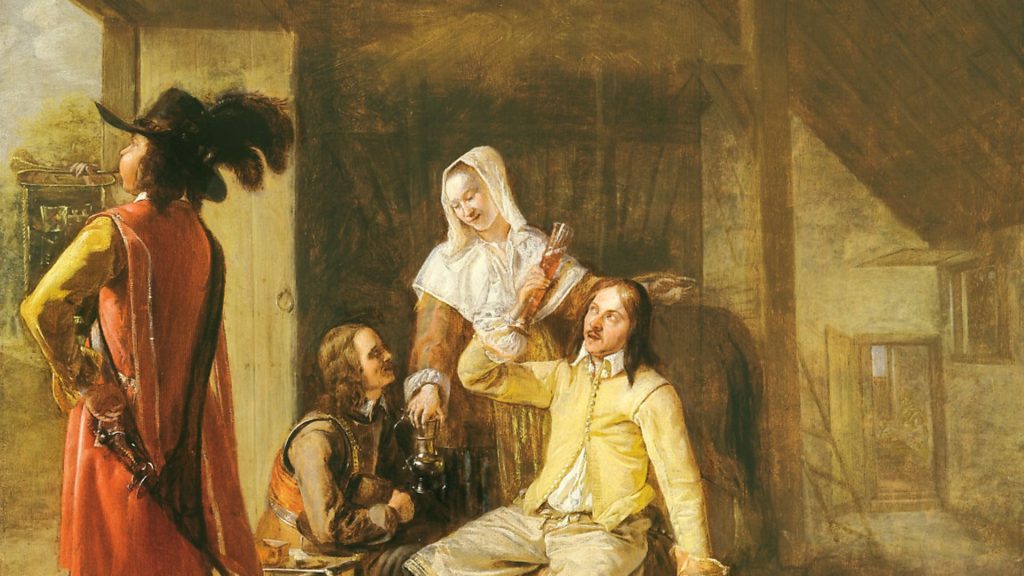

In truth, de Hooch’s early offerings weren’t especially memorable. He produced work in an established Dutch genre known as the guardroom scene. This consisted of soldiers in dark, indoor quarters engaged in pursuits such as drinking, smoking and card-playing.

It wasn’t long, though, before the artist made his big breakthrough. Or, to be precise, his two big breakthroughs – with depictions of goings-on in people’s backyards; and scenes inside houses, complete with ‘through-views’ leading our gaze via a doorway or window to a different scene beyond.

In both cases, de Hooch was going where no painter had gone before. Among his finest backyard scenes is Woman and Child in a Bleaching Ground (1657-58), in which a girl watches her mother lay out a load of linen in the sunshine for whitening.

The spire of Delft’s Oude Kerk (‘Old Church’) – a feature in many of de Hooch’s outdoor scenes and still a landmark today – looms in the background.

What we might call de Hooch’s golden period – that of the backyards and through-views – began in the mid-1650s. His works from this time moved away from conventional perspective with a single vanishing point, in favour of a more complex perspective scheme. They also boast the fall of light at ingenious angles.

If that makes de Hooch sound more of a geometrician than an artist, let’s remember optical wizardry was always twinned with humble subject matter. One of the standout paintings of his career, A Mother’s Duty, depicts a woman delousing her child. (In the corner of the room, de Hooch also included a large kakstoel – which translates, rather inelegantly, as ‘a child’s toilet chair’).

As for the relationship with Vermeer, frustratingly no documents exist shedding light on their interactions. Nor, for that matter, are there any tales – apocryphal or otherwise – of daggers drawn.

What does seem fair to say, though, despite their respective statuses today, is that de Hooch was the more innovative. Both could pull off clever tricks with perspective and light; both enjoyed painting a well-positioned ‘through-view’; both liked to depict everyday action in everyday bourgeois homes. However, it was de Hooch who by and large did this first.

Proof comes with his Woman Weighing Gold and Silver Coins, a canvas remarkably similar to Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance. So similar, in fact, that whoever painted his second was surely trying to emulate whoever painted his first.

Each features a female in a bonnet and blue jacket, weighing coins at a table (common practice at the time, as a coin’s weight determined its value). Each female is also illuminated by a burst of light entering from a window on the left.

The curators’ research confirms de Hooch’s picture was painted before his counterpart’s.

Sir Michael Levy, director of the National Gallery from 1973 to 1986, once claimed he’d have swapped 10 Vermeers for a single de Hooch. Clearly that was – and still is – a minority view, however. For the truth is that, though de Hooch may have done things earlier, Vermeer did things better. And it’s no slight on de Hooch to say so. His peer managed to invest paintings with a kind of magic that precious few others in history have come close to.

Where de Hooch’s pictures are worldly, Vermeer’s are almost otherworldly. Part of the latter’s success comes down to the way he probed the psychological state of his subjects, thereby creating hints of drama in every scene. De Hooch, by contrast, had little time for human emotion. For him, drama came purely in the movement of light as it hit a wall or floor.

At the turn of the 1660s, de Hooch left Delft for Amsterdam, where he’d spend the rest of his life. His final years weren’t especially happy (and even included a spell in a lunatic asylum).

The exhibition features just a handful of his Amsterdam paintings, its curators arguing – quite rightly – that the bigger, richer city saw a drop in quality. De Hooch’s work there tended to depict the flashy homes of his moneyed new clients, yet it lacks the evocative atmosphere of old, almost as if his heart wasn’t in it.

The show focuses on the artist at his best, then: During his Delft years. In the century or so after his death, he seems to have been regarded as just another Dutch painter. The Parisian art dealer, Alexandre-Joseph Paillet, expressed a widespread view when he said “I do not place the paintings by this master in the first rank”.

Gradually, the prices for de Hooch’s work rose, and in the 19th century it began to be collected internationally – by the likes of King George IV and Sir Robert Peel in this country. However, it was also about this time that a cult developed around Vermeer, who became dubbed ‘the Sphinx of Delft’ and was soon the only artist connected to that city anyone really cared about.

Which is what makes the current show so welcome. De Hooch can finally now emerge from the long shadow cast his rival. Or, to use a different metaphor, he can finally now emerge from art history’s backyard.

Pieter de Hooch in Delft: From the Shadow of Vermeer is at Prinsenhof Museum Delft, until February 16; prinsenhof-delft.nl +31 15 260 23 58