What does a winter poll mean for Remain? Mathematician CHRISTINA PAGEL calculated the prospects of various scenarios and believes it offers the best chance of ultimate success.

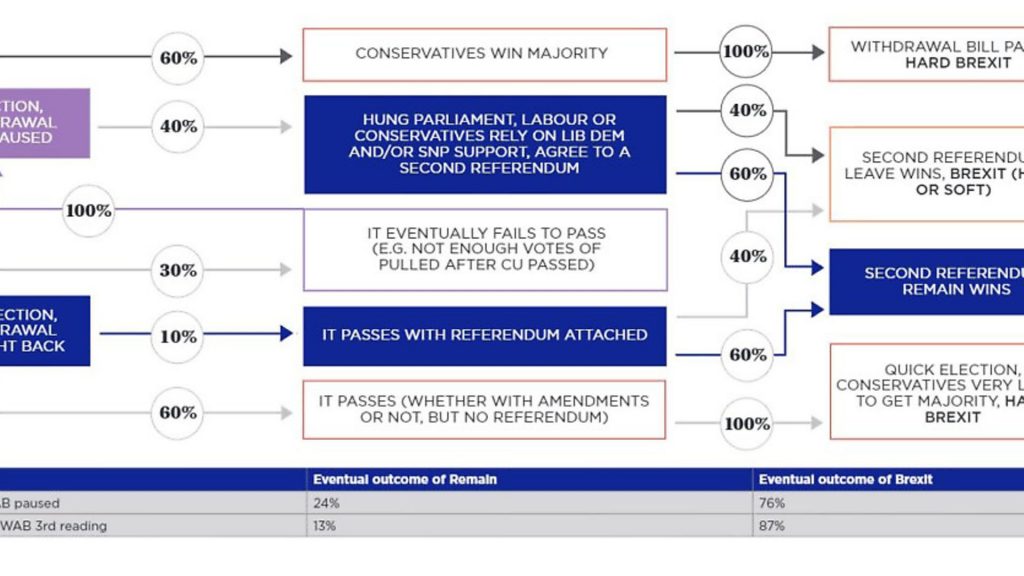

Arguments about the pros and cons of a general election have been raging on Remain Twitter, so I thought it would be helpful to highlight where people are disagreeing and what probabilities they think are markedly different. The probabilities I have used are my estimates and are not based on modelling – although they are informed by polls and my reading of what is going on.

If there had been a new referendum, it would have been against a backdrop of all the polls showing a small but consistent lead for Remain. So Remain would have been favourite but not a strong favourite – a lot would have rested on the campaign and turnout. I’ve estimated a 60% chance that Remain would have won (whatever the Leave option was), but it could be as low as 50% or as high as 65%.

Now there will be an election, with the Withdrawal Bill paused. We will still be in the EU and the Conservatives will be campaigning on a ‘people versus parliament’, “let’s get Brexit done” message. The polls show them with a healthy lead nationally, but the Liberal Democrats and Labour are often not competing against the Tories in the same seats – so at a constituency level, things are a lot more uncertain, and if the Remain vote coalesces around Lib Dems and Labour in key seats then things could be very different.

The Tories look set to lose their seats in Scotland and possibly some south western and London seats to the Lib Dems, so they need to pick up current Labour Leave constituencies. However, many Leave voters in those seats weren’t Labour voters to begin with (and Tories won’t be picking up Labour Remain voters), while many Labour Leave voters who abandon their party still have tribal antipathy to voting Tory and will either not vote or support the Brexit Party instead. Polls suggest that defecting Labour Leave voters in the north are much more likely to vote Brexit Party than Conservative. London is a genuine three-way battleground between the Tories, Lib Dems and Labour where results could hinge on tiny margins.

This makes it all so volatile and unpredictable. I’ve estimated a 60% chance that the Tories win a majority, but I think it could be as low as 40% or as high as 75%. And the campaign will change things again. I don’t, however, see a Labour majority. They have lost many of their 2017 Remain voters who don’t seem in a rush to come back. Labour are likely to do very badly in Scotland, may lose some of their London seats to the Lib Dems and of course the Tories are targeting their northern seats. They were 60 seats short in 2017, so I just can’t see a route to a Labour majority in 2019.

So the only thing that is left is a hung parliament (with probability 100-60=40%), where either the Tories or Labour are the largest party and need the support of either the Lib Dems or the SNP or both. I can’t imagine the DUP supporting either party. In that case, the price for government will be a referendum on a deal (either the existing one or a new Labour one depending on who is the largest party) and we are at the second referendum scenario above. The probability of Remain succeeding in this scenario – 40% (hung parliament) x 60% (Remain wins) – is 24%.

On the other hand, if there had been no election, and the Withdrawal Bill was brought back to parliament (because what other option is left?), it would have either passed with a referendum attached, passed without a referendum attached or if it failed for whatever reason, either Johnson would have tried again for an election or Corbyn would have won a vote of no-confidence and an election (again, what is left to do other than an election? And this would still be early enough for January 31 not to present an imminent no-deal threat).

The Bill had a reasonable majority for its second reading and we know that around 19 ex-Tories and about 20 Labour MPs really wanted to vote for a deal – they didn’t like this deal but it’s all there is and with some amendments, enough of them are likely to vote for it to allow it to pass. None of these MPs wanted a new referendum. This is why, had things gone differently, I’ve estimated that the chance of the Bill passing without a second referendum at about 60% (it could have included a customs union though, or more workers’ rights or automatic extension of transition period).

In our alternative universe, had it passed without a referendum, we would have left the EU and I imagine a quick general election would have followed after that (again – what else is there for parliament to do given Boris Johnson has no majority? The Lib Dems and SNP, meanwhile, would have been keen for an election to capitalise on anger at Labour if their votes help the legislation pass). I also think that if we were in a transition period with no immediate negative impact of Brexit evident, Johnson would have won a majority on his ”I got Brexit done” message. With a majority, he could have negotiated a hard Brexit, since the future relationship is not set in law.

That said, MPs are unpredictable and so I’ve estimated a 10% chance that a referendum amendment might have passed with the Bill (and that the government then implements it – which is far from certain). In fact I think 10% is pretty generous. The probability of it failing was then just 100-60-10%, so 30%, and includes all the different ways of it failing. (It could have failed quickly or slowly if various amendments are passed that stop, say, the European Research Group voting for it, or the government pulled it if a customs union is passed).

The probability of Remain emerging triumphant in this scenario, then, was: 10% (Withdrawal Bill passes with a confirmatory People’s Vote as a condition) x 60% (Remain wins the subsequent referendum) + 30% (the Withdrawal Bill fails and a general election is held) x 40% (we end up with a hung parliament) x 60% (Remain wins a second referendum that is agreed as a price for governing) = 6%+7% = 13%.

These are my estimates and I invite anyone to try out their own estimates of the chances of different outcomes happening. In my opinion, an election now, while daunting for those desperate for Remain, nonetheless represented the best chance Remainers have.

Professor Christina Pagel is director of the University College London Clinical Operational Research Unit (CORU)