Surrealist comedian Ernie Kovacs remains a relatively obscure figure here BENJAMIN IVRY celebrates the genuine pioneer of the small screen.

If hardly a household name even in his homeland, the American comedian Ernie Kovacs – born 100 years ago this month – remains worshiped by the cognoscenti. In 2011, Monty Python member Terry Gilliam told Bright Lights Film Journal: ‘The Ernie Kovacs Show knocked me sideways into a world where the bizarre and the daft and the preposterous all lived happily alongside wisdom, wit and perception. I had never experienced anything so visually absurd and inventive.’

In his Complete Unreliable Memoirs, Clive James put him in an elite group of television entertainers: ‘Totally original innovators – Ernie Kovacs in the US, Spike Milligan and Kenny Everett in the UK – are very rare.’

Indeed, Everett’s habit of breaking away from sketches to address the audience directly is thought by some observers to possibly derive from Kovacs’ precedent. Certainly Benny Hill’s rapid fire gags were also in the line of Kovacs, whose renown in the small screen was mostly limited to the United States, although always hunting for material and influences, astute English comedians surely took note of his achievements.

A genial, distracted, moustachioed presence onscreen, Kovacs appeared to be chuntering along in his own little world of comedy, surprisingly heedless of audience response. Kovacs’ catchphrase, ‘It’s been real!’, with which he regaled viewers, was repeated in Douglas Adams’ Life, the Universe and Everything, the third book in his Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series. Adams had the cryptic phrase uttered by a snobby art world figure.

Kovacs, alert to societal trends such as the Beat generation, referred to realness as a possible stretch for coolness, while also playing off the obvious fact that his programmes purported to show anything but unadorned reality.

A series of counter-narratives consisting of conceptual japes, the typical Kovacs show would offer snippets such as Romantic music accompanying a morbidly obese ballerina moving en pointe toward the camera before her over-stressed ankles give way. This Pythonesque image might have been invented for animation by Gilliam. In an advert devised for a sponsor, Kovacs and another actor were dressed as cowboys at a showdown, each smoking cigars. Kovacs shoots his adversary, from whose bullet wounds emerge puffs of smoke. This somehow recalls the Black Knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, who loses limbs aplenty while likewise retaining his sangfroid.

In another visual jest, a young woman taking a bath is nonplussed when a submarine’s periscope emerges from the depths of the tub. A notion not unworthy of Benny Hill. Kovacs worked on a shoestring budget, yet tirelessly created sight gags with the dedication of some of cinema’s most honoured comic minds. In one complex scene filmed underwater, Kovacs sat in a chair, reading a newspaper, with a cigar in his mouth. Removing the stogie from his mouth, Kovacs appeared to exhale a puff of white smoke, which was in reality a bit of milk which he had been holding in his mouth.

He was no less punctilious about devising new camera techniques, with a fierce willpower akin to that of Buster Keaton in an earlier era. Indeed, were it not for Kovacs’ untimely death in an automobile accident, in 1962, he would have starred in a television series as a vendor of patent medicines in the Wild West, assisted by the venerable Keaton as an Indian brave.

Although pulmonary problems kept him out of the US military, Kovacs belonged to the generation of the Second World War, which confronted a world where nuclear conflict was seen as a distinct possibility. In his own family history, his Hungarian-born father had been a police officer before making an ephemeral fortune as a bootlegger. Small wonder that a repeated theme of mayhem was visible in Kovacs’ humour.

Attending a concert where a recording of the notoriously off-key soprano Florence Foster Jenkins was played off camera, he assembles a rifle and fires it, supposedly silencing the off-key diva. In another episode, a Wagnerian soprano wanders offstage to find a pistol and shoots Kovacs, whose baritone voice in an operatic duet displeased her. A parody quiz show entitled Whom Dunnit features a studio audience member who has been shot by a celebrity, and the panel must guess the name of the perpetrator. The injured party, played by Kovacs, expires before a conclusion is drawn. In another violent rethinking of the quiz show format, a show entitled Whip the Wristwatch features host and contestant in a gun battle, with the latter being wounded in the leg.

In Kovacs’ universe, shooting occurs from all directions, however unlikely. At a carnival, a duck in a shooting gallery takes aim and shoots back at a punter. A television viewer is shown at home becoming gradually irked by a television host for tots, Freddy the Friendly Fireman. Finally the viewer fires a gun at the host, and the camera pans to the television screen whereupon the now-dead Freddy hangs out of the screen as a sort of trophy of the hunt.

Even in a comparatively innocuous take-off on a children’s show, Kovacs as a garlicky Hungarian host is annoyed by a marionette and clips its strings with a pair of scissors, leaving it slumped and inert. As a latter day variant of the castrating symbolism of the Scissor-Man in Shockheaded Peter, the result is juvenile trauma. Previously boisterous kiddie spectators are silenced by the brutal finality of the gesture.

It is only natural that one of Kovacs’ most vehement admirers should be Martin Scorsese. The director of Goodfellas told Film Comment in 1990 that the deliberate lack of focus on narrative in that film when describing offscreen violence was inspired by Kovacs: ‘I learned a lot from watching [Kovacs] destroy beautifully the form of what you were used to thinking was the television comedy show. He would stop and talk to the camera and do strange things; it was totally surreal.’

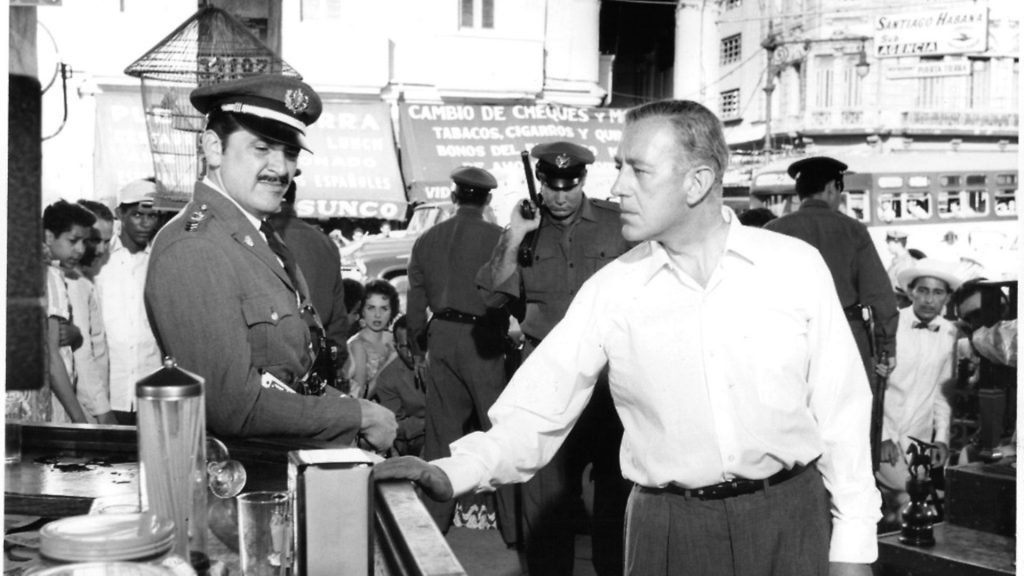

Considering how Kovacs could influence cinematic art, his own film career was relatively conventional. Perhaps being dependent on following scripted dialogue instead of his own wild fancy was to blame. In Carol Reed’s 1959 screen version of Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana, he was cast against type as the sinister Captain Segura. More in his bailiwick was the 1957 military comedy Operation Mad Ball, a tame outing mainly remembered today for Kovacs’ wild theatrical trailer for the film, where he was left to his own devices. Spoofing the very notion of a trailer to attract audiences, this brief effort remains as fresh as when it was filmed.

Perhaps his most characterful onscreen turn was as a drunken author on occult subjects in the underrated comedy Bell, Book and Candle (1958), starring alongside Hermione Gingold and Elsa Lanchester as witches.

In 1986, America’s Museum of Broadcasting praised Kovacs as ‘television’s first significant video artist’. He has also been described as television’s ‘first video auteur’, who used ‘broadcast video as an art form’.

Like some video creators in the highfalutin art world, he was essentially a conceptual artist. Some of his gags, such as a group of men in gorilla costumes performing an excerpt from Tchaikovsky’s ballet Swan Lake, are better as ideas than actual performances.

And like many clowns, when Kovacs strove for artistic seriousness, the results were far from his most effective. One city scene using necessarily modest miniatures of buildings was set to Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra. Yet the threadbare staging of interactions among a delinquent, a floozy, and police officer are reminiscent of Busby Berkeley’s stereotyped urban allusions in the choreography of the 1933 film musical 42nd Street.

Even on happier occasions, Kovacs merely shows what he might have done with a larger budget. A devotee of silent film, in another scene he portrays a character who removes his lunch from a box. One by one, the items roll away, impelled by a mysterious slanted gravitational force. He pours milk from a thermos bottle and it, too, flows at a slant. The effect was realized by using a tilted set filmed by a camera tilted at the same angle. A similar tour de force was achieved earlier in the director Stanley Donen’s musical comedy Royal Wedding (1951), in which Fred Astaire dances on the walls and ceilings of a room to express infatuation.

As a video artist, Kovacs was not fond of live audiences, since his comedy was so solidly based on what could be seen on the screen at home. Just as the pianist Glenn Gould preferred studio recordings to live concerts, Kovacs was in his element in a laboratory-like setting where his imagination could run unrestrained.

Unperturbed by the notion of leaving most viewers adrift, he guaranteed that his shows would remain catnip for the happy few. The vast public of American TV-land felt more secure among traditional braying laugh tracks of sitcoms and variety banalities.

Kovacs’ early death was a decided loss to the world of comedy, not just in America. The only bright side was that it spared him having to appear, as he was contracted to do, in the heavy, tedious, and unfunny It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963) directed by Stanley Kramer. But then, Kovacs’ potential parody of this elephantine effort might have tickled television audiences and posterity, as his life’s work still does, resoundingly so.