The medical protocols that helped saved Denmark’s Christian Eriksen are partly down to the work of one man, football doctor Michel d’Hooghe

It was a Swedish writer, Erik Niva, who observed last Saturday: “Denmark lost but life won”. He reported on the collapse, the apparent death, and then the resuscitation that saved the Danish playmaker Christian Eriksen during play in Copenhagen against Finland.

In those words, Niva put into perspective the extraordinary power, the hope and the horror, of sport in this year of dreadful uncertainty in all our lives.

The madness of Euro 2020, this delayed tournament of 51 games scheduled over 31 days across 11 countries during a pandemic, was somehow encapsulated in that short sentence.

Eriksen, 29, a marvellously gifted player for Ajax Amsterdam, Tottenham Hotspur and currently Inter Milan, was in the prime of life one minute, dead the next, and then through the rapid action of his team captain Simon Kjaer and the instantaneous intervention of medical science was able to ask his shocked countrymen to play the remainder of the game after a 90-minute delay.

Nothing and no-one will mean more throughout the rest of this sporting summer. Not the incredible comeback of Novak Djokovic to win the French Open final on Sunday. Not the small “miracle” of England winning its opening game in European competition for the first time in history. And not Belgium, opening its tournament without three of its “Golden Generation” players, so completely outplaying Russia in St Petersburg that the Belgians won 3-0 seemingly at walking pace.

Talent and temperament usually in the end determine sporting outcomes. But we cannot, should not, simply note Eriksen’s collapse and move on as if nothing out of the ordinary happened at the Parken Stadium.

The team doctor said, simply, that Eriksen was “gone”. Dead. In cardiac arrest, until a defibrillator was used to shock his heart back into rhythm.

And then within an hour, the dead man was talking over FaceTime to teammates from his hospital bed, urging them to carry on. It was relatively unimportant that Finland scored the only goal – or that Denmark failed even with a penalty kick.

As Niva so perceptively said, Denmark lost but Life won.

It is important to explain why. Almost 50 years ago, Michel d’Hooghe, a newly qualified doctor volunteering his time to his local team Club Brugge, ran onto the field to give mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to Nico Rijnders, a young Dutch player who, like Christian Eriksen had come through the Ajax youth system.

The difference was that Eriksen had no known symptom of heart problems. Rijnders, it turned out, had been sold to Brugge despite experiencing alarming breathing problems earlier in his career. D’Hooghe saved him on the pitch, but though Rijnders never played again, he died three years later of congenital heart disease.

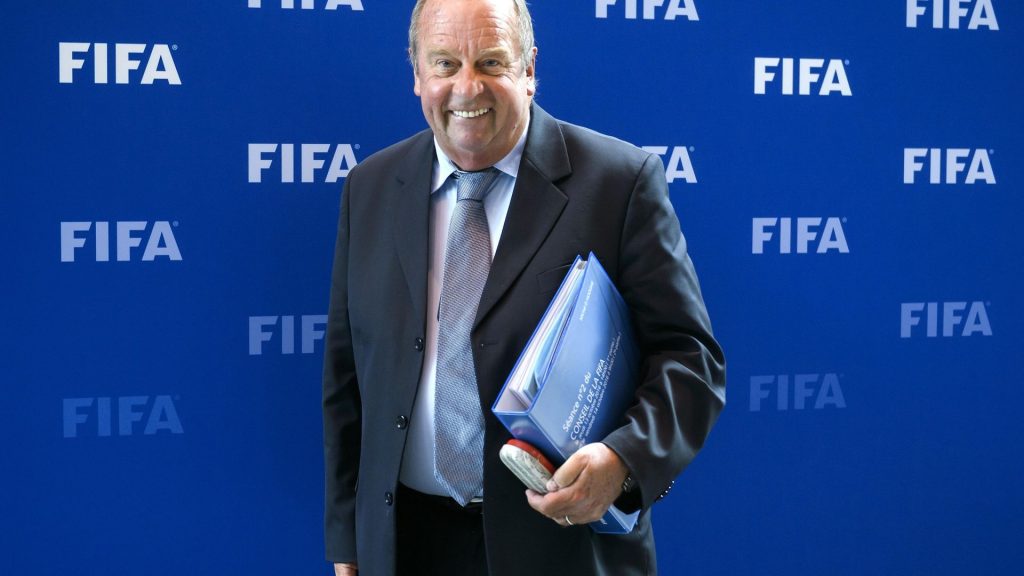

That incident never left Dr. d’Hooghe. I have known him personally through most of the 33 years he subsequently served as chief medical officer to FIFA, the world governing body of football.

And apart from running his own rehabilitation centre in Brugge, d’Hooghe is responsible for forcing reluctant clubs and national associations the world over to spend the relative pittance it took to insist that every professional club, every association, invest in defibrillators to shock the heart into action, and in medical apparatus to check and monitor the 260 million players affiliated to FIFA around the world.

Even so, even today, we are shocked, frightened, by the dreadful paradox of apparently fit sportsmen collapsing on the field of play. Who can forget Marc-Vivien Foe, the dynamic Cameroonian midfielder, dropping unchallenged to the ground during the FIFA Confederations Cup in Lyon in 2003 – dead beyond revival? He was 28 and, having already played in the Premier League for West Ham, would have been a key player in Manchester City’s first season at the Etihad Stadium; the start of their rebirth.

Younger players, to all intents and purposes as fit as we thought Eriksen to be, have died in action in all parts of the world. Brazilians, Hungarians, Spanish, British, Italian, Japanese… the list is global. Extreme heat is sometimes a factor, but not in Copenhagen on a Saturday evening; and not, we thought and hoped, in the early throes of a tournament that was supposed to reflect life regaining at least a semblance of normalcy after the dread of such a long and deadly dance with a virus no-one knows how to beat.

In these circumstances, it is remarkable that professional sport keeps on playing. And keeps the power to lift, to stir or depress us. To provide an outlet of hope and exhilaration, a pretence that all is well with the world.

The Euro is in its infancy. Forgive the Englishness of the following observations but if this tournament runs its course, the final three games offer a gilded opportunity for England to be significant in a major football event for the first time since 1966.

The semi-finals and final are scheduled for Wembley Stadium. The first English goal was scored by Raheem Shaquille Sterling, born in Jamaica, raised in the shadow of Wembley Stadium, and one of the faces of the Black Lives Matter campaign against the abuse that sports players still get because of the colour of their skin.

One week before his goal against Croatia, Sterling was awarded an MBE “for services to racial equality in sport.”

His goal was set up by the most inspiring player on the pitch, the Leeds United midfielder Kalvin Phillips. The son of a troubled Jamaican father and an inspirational Irish mother, Phillips is extraordinary in that we do not yet know how good a player he may become.

He was 24 before he played in top professional football. He came through the ranks as a Leeds academy boy, and maybe it took the remarkable Marcelo Bielsa, an Argentine who coached, coaxed and cajoled Leeds out of its long slumber outside the Premier League, to reshape his knowledge of the game and to reset his horizons.

Anyway, the Leeds faithful call Phillips ‘The Yorkshire Pirlo’, comparing his movement and vision to one of Italy’s all-time pass-masters, Andrea Pirlo.

Small world: Pirlo has just been sacked as coach to Juventus. Phillips, in mid-career, is being hailed as a future great of the game.

And Eriksen is alive.