Despite attempts to bridge it since the fall of the Iron Curtain, the chasm between Eastern and Western Europe remains wide. The pandemic has pushed the two regions even further apart.

No-one better embodies the liberation of Central and Eastern Europe from Communism than Vaclav Havel, the Czech playwright, dissident and first democratically-elected president of the modern era.

On Havel’s death in December 2011, David Cameron declared: “he helped bring freedom and democracy to our entire continent.”

As Havel himself might have quipped: if only it had been so simple.

Two quotes from Havel himself describe the impediments he faced at the time, and the limits of the achievement that were to follow. “We cannot blame the previous rulers for everything, not only because it would be untrue, but also because it would blunt the duty that each of us faces today: namely, the obligation to act independently, freely, reasonably and quickly,” he said in his New Year’s message in January 1990, two months after the Velvet Revolution.

A year later, as cracks were already beginning to emerge, he spoke of a “contaminated moral environment”, noting: “Today we all are made somewhat nervous by the burden of freedom.”

Across swathes of what used to be known as the Warsaw Pact, hopes of a liberal reawakening have been either dampened or destroyed by a combination of factors – economic sluggishness, migration, corruption, the weakness of the rule of law, and the attractiveness of easy solutions provided by nativist-nationalism.

And that was before Covid.

As Europe seeks to clamber out of its latest crisis, democracy across the eastern half of the continent has never looked so precarious. Moreover, it seems safe to predict that the political, economic and societal outlook is about to get a whole lot bleaker.

According to a report by the European Bank of Reconstruction (EBRD) and Munich-based IfO Institute, all the examples of increasing inequality that Western European states have demonstrated since the start of the pandemic are replicated in the East – but in far greater proportions.

The disadvantaged, or “left behinds” have been far more susceptibility to the virus itself, and more likely to have lost their job and to have seen their overall prospects suffer significantly more than the rest of the population. In other words, the worse-off you were to begin with, the more you will have been screwed.

The gap between the metropolitan middle-class and the rest, which has been at the heart of the culture war of recent times, is set to increase, but at a faster rate, than in wealthier countries.

For example, stimulus packages have been far less generous in the East, leading to more family businesses in small towns and villages going to the wall.

By contrast, the digital transformation, which might have taken five years or so, has been concertinaed into just a few months. From home working to e-shopping, the geek generation have not just survived but have laid the foundations potentially for a strong future.

Young people in the former communist states have long been seen as ideal recruits for Silicon Valley and other tech firms: hard-working, flexible, dynamic and with strong coding skills.

“Older workers have weaker ICT than their equivalents in G7 countries,” Beate Javorcik, chief economist at the EBRD, tells me. “Accelerating digitalisation during coronavirus is exacerbating inequality.”

The overall westward migration of the young and ambitious was largely halted at the start of the first lockdown, when borders closed in countries like Germany, France and the Netherlands and the first wave of redundancies was announced.

Some Eastern European migrants had no choice but to return home, with no job or remittances to help families and friends. Those tended to be the less skilled, however. The same applied in the other direction, with Ukrainians leaving Poland.

The better skilled either stayed in the West in their white-collar jobs or are set to return in coming months, once restrictions are eased. The brain drain of Eastern Europeans in search of a better life shows no sign of abating – even if getting to the UK, post-Brexit, has become much harder.

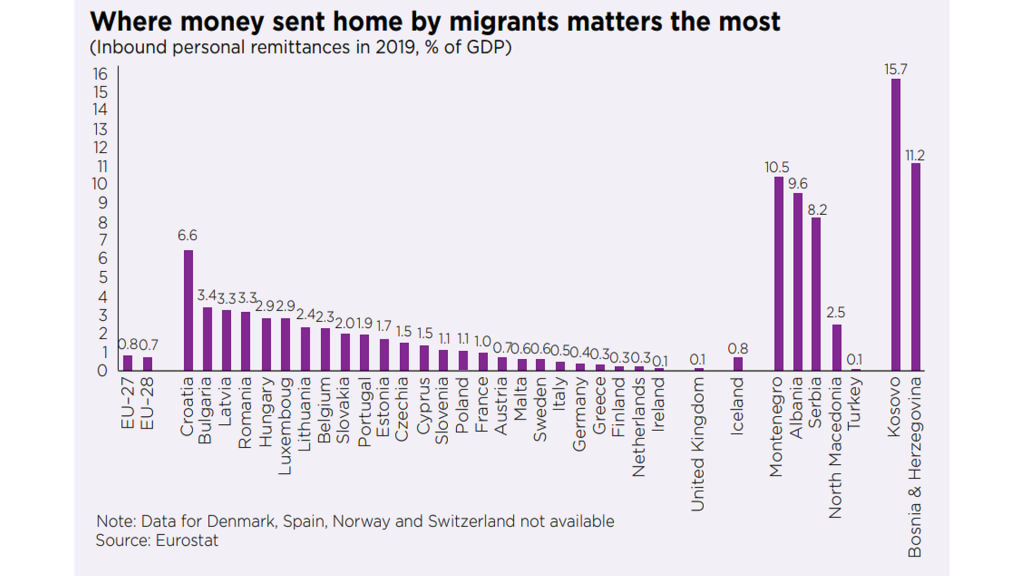

In the poorest countries, the loss of employment opportunities abroad is threatening already low living standards. Countries such as Albania, Bosnia, North Macedonia and Montenegro have been exporters of labour to Western Europe for decades.

The pandemic has had a triple negative effect on the Balkans: it reduced remittances from abroad (which in some countries exceed 10% of GDP); it increased local unemployment and it put additional pressure on social services. Data from the National Bank of Serbia show that personal money transfers fell by a third in 2020, year on year. It will take years for these countries to recover.

Meanwhile, the political divide, stark enough as it is, will intensify yet further. According to the EBRD’s Javorcik, other Covid-era factors will reinforce this.

One is the role of the state. In Central and European Europe, as liberalisation took hold in the heady early post-communist years, the state’s share of total employment declined from around 45% in the mid-1990s to 24% in the mid-2010s. Since then the rate of decrease has slowed and, in the minds of many in the West and East, the pandemic has rehabilitated the state as a guarantor of health and security.

With that comes an acceptance, whether grudging or not, of the state as having a greater hold on individuals’ lives. According to the latest Transition Report by the EBRD, entitled “the state strikes back”, some 45% of people in post-communist countries favour an increase in public ownership.

That is higher than it was, and higher than the equivalent surveys in Western Europe, which put the figure at 35%. Older cohorts, particularly those who cling to the stability of public-sector job, are more likely to want the authorities to play a bigger role overall.

For the region’s authoritarians and wannabe strongmen, this is manna from heaven. The two most notorious leaders, Hungary’s Viktor Orban and Poland’s prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, have used the pandemic as an excuse to crack down further.

The ruling Law and Justice party in Poland and the Fidesz government in Hungary have taken a series of incremental steps to snuff out the two most important checks on their power – the judiciary and the media.

Hungary’s last remaining independent broadcaster, Klubradio, has in the last few weeks been forced off air. In Poland, more than 40 Polish media companies took part in a 24-hour blackout protest last month, in opposition to a draft law that is set to introduce new taxes on advertising. In both countries, smart tools are being used to shut down dissent. Instead of locking people up – that would be too crude, too Putinist – pliant courts enforce labyrinthine rules.

The Polish government has declared that it needs new revenues to use in the fight against Covid. Half the money used from the new tax will go to the health services, while 35% will go towards a newly created “Fund for the Support of Culture and National Heritage in the Sphere of the Media”: in other words, journalism that supports the regime’s nativist nationalism. To reinforce the point, businesses that seek government contracts, still a huge part of the corporate economy, are discouraged from advertising in “disloyal” outlets.

Neutering the media has two powerful benefits. It reinforces central power, and it removes scrutiny of the links between politics and business. Rampant corruption and cronyism go un-investigated as a result.

“Governments should help media stay on, not go dark,” Vera Jourova, vice-president of the European Commission tweeted. The EU’s push-back against authoritarianism from within its own borders has been patchy, to put it politely. The enlargement of the bloc in 2004, the addition of eight new members from the east which Britain ardently supported before being spooked by the labour-market consequences, was supposed to cement their integration into not just structures but also value systems.

It started well. All of the countries benefited from infrastructure projects funded through regional development funds. Political and economic regulations were reformed to meet the requirements of accession. Freedom of movement was supposed to lead to a flourishing of enlightened ideas.

Since the financial crash of 2007/8, as the EU became further embroiled in its own woes – the Greek debt crisis and then the great refugee wave of 2015 – it has equivocated on its core values, opening the door for populist regimes from within its midst to reinterpret what were supposed to be common rules as they see fit.

While the overall picture is bleak, there is the odd sign of hope.

In the Czech Republic, a new movement formed from student protests is seeking to turn itself into a political party that can take on prime minister Andrej Babis in October’s parliamentary elections. In neighbouring Slovakia, while successive governments have been mired in scandals, not least the targeted killing of an investigative journalist in 2018, two leading politicians give rise to optimism.

One is the president, Zuzana Caputova, an environmental activist; the other is, Matus Vallo, Mayor of the capital, Bratislava. Both are fighting rear-guard actions against populists, who, as across the region, are playing on citizens’ fears. In recent weeks, the pandemic has struck back in Slovakia, which is already one of the most affected economies in the EU, with one of the fastest-growing unemployment rates.

Geography and history are not always reliable guides. Slovenia, which borders Austria and was during the time of Tito seen as Yugoslavia’s window on the West, is now in the grips of an assault on the media and other pro-democracy institutions. Its prime minister, Janez Jansa, is a carbon copy of Hungary’s Orban – an anti-communist dissident turned alt-right, Trump-loving populist.

By contrast, Moldova, which struggles to extricate itself from Moscow’s grip, recently elected a pro-Western liberal, Maia Sandu, as its president. Her chances of surviving long seem narrow, however, as parliament is under the control of pro-Kremlin parties.

The three Baltic states have refused to buckle to the populist wave, although nationalist parties have gained ground in a number of elections. Geo-strategically they remain firmly orientated towards the West and are more outspoken in supporting opposition movements in Belarus and Russia. Symbolic it might have been, but it did not go unnoticed that on February 7, the foreign ministers of Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania issued a joint statement to mark the international Day of Solidarity with Belarus.

The one factor that does appear to be broadly consistent is the split between the big cities and the rest. As Misha Glenny, long-time observer of the region, points out: “The biggest long-term trend in Eastern and South Eastern Europe is the demographic decline.” The flight of young people with good educations out of medium-sized towns and into either their countries’ capitals, or abroad, is reinforcing the divide, he says.

Meanwhile, the search for investment continues apace. It had been regarded as axiomatic that the more the influence of Western European and the United States waned, particularly during the Trump era, the more the region would succumb to China’s economic blandishments. Greece sold off its main port, Piraeus; Serbia was thankful for new bridges; Minsk offered itself up as an important trading port for the Belt and Road railway.

Much of that remains, but the picture is not as rosy as Beijing would have expected. At a recent online summit of the 17+1 (China and 16 Central and European states), Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Slovenia, Romania and Bulgaria only sent junior ministers in a clear snub to president Xi Jinping.

As ever, the EU struggles to agree a coherent position on Russia and China. And yet what is remarkable is that countries that would have been regarded as in the heart of the Western alliance, such as France, are more eager to please Beijing, whereas some in the East are taking a tougher line.

If infrastructure is less seductive than it was, how about medical help? The bungling of the vaccination programme by the European Commission has opened the door for the Chinese and Russians to try to flog their own. A number of individual countries have already signed deals. Thanks to the pandemic, everything is up for grabs.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk