ROB HUGHES examines England’s near-miss at the Euros and finds that for all their advantages, a change of mindset is necessary at the top

So near, and yet so far. England released itself from the European Union, but remain far from the world-beaters some fans imagine it is their birthright to be as the motherland of football (sorry, I hate that appallingly unmusical dirge “Its Coming Home” too).

How crass it was for failed politicians to write piffle about the Euros conquering the global game and simultaneously unlocking the Covid curfew. Sunday was a lesson in two acts in one city – opening up Wimbledon and Wembley to mass audiences with royal patronage in both houses.

The tennis crowd behaved. Football was infiltrated – like a burp from the dark past – by hooligans who stormed the gates and by anonymous cowards using so-called social media to racially abuse young players whose families are part of the British colonial diaspora.

In the aftermath of all this, Gareth Southgate displayed his dignity and decency by taking the blame for choosing the penalty takers. He should instead reflect on the flawed tactics that made his England novices of negativity. You do not beat the Azzurri at THAT game.

England is the mother of the game. Italy is the Machiavellian master of winning negatively. England asked youth to come coldly off the bench for that horribly contrived penalty pot-shot. Italy’s gnarled, artful, cunning old-timers Giorgio Chiellini and Leonardo Bonucci proved once again that experience trumps youth in the end.

We saw this coming, paying tribute earlier in the tournament to the Italian renaissance, the remaking of the Azzurri under Roberto Mancini (TNE #250). The former Sampdoria striker and former Manchester City manager rebuilt Italy from a team that failed to even qualify for the 2018 World Cup to one that, despite injuries and despite the decline of the Serie A domestic league, is now unbeaten in 34 international games.

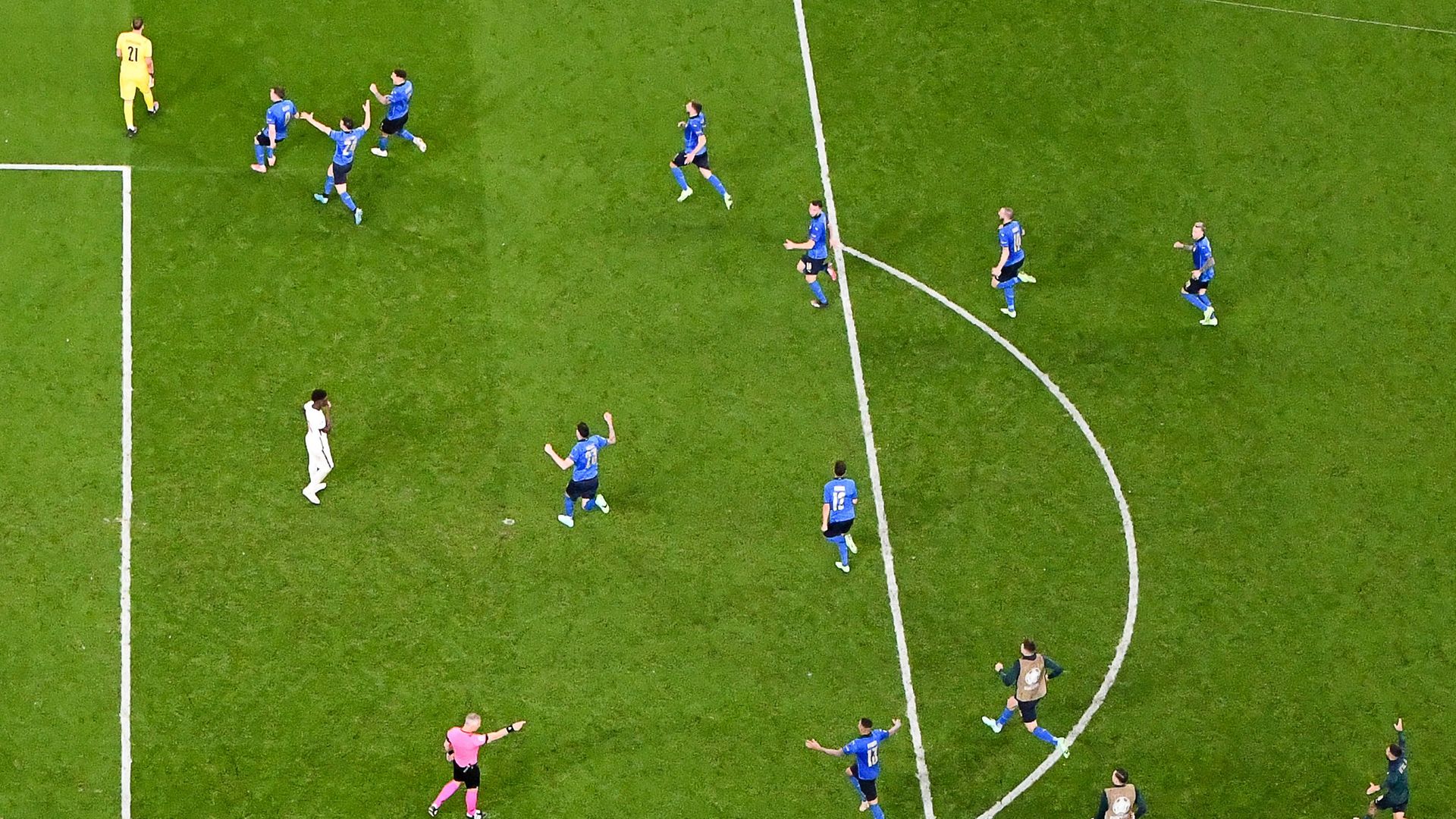

Mean and magnificent. And so it is Italy who are the true blue winners, England the nation who have still not won a senior tournament since 1966 at the old Wembley under the Twin Towers.

Sir Geoff Hurst, one of four surviving members of that triumph of 55 years ago, was actually at the new Wembley on Sunday evening. Could anyone imagine Hurst, the hat-trick hero of his Wembley showpiece, not getting one shot in the penalty box in the 90 minutes and extra time?

That was the fate, the tactic, of captain Harry Kane on Sunday.

Kane, despite his journey of perseverance through years of being doubted and loaned out by Tottenham, was actually a key member of England squads at Under-19, -20 and -21 level.

And Kane is now the leader of the next generation – the group including Phil Foden, Jadon Sancho, Callum Hudson-Odoi, Emile Smith Rowe – who triumphed at Uefa and FIFA youth tournaments.

England actually learned the lesson from Spain and Italy and Germany that it makes sense to promote a head coach through the ranks of Under 21 to full international teams. Hence Southgate is the FA’s man for continuity.

The brave Bukayo Saka. The bold but injured Phil Foden. The daring Jadon Sancho and Jude Bellingham, who took the chance to go abroad and further their football education in Germany.

Sancho is “coming home” with a record transfer fee paid to Borussia Dortmund by Manchester United. Yet he was given just one full game (a sparkling one) by Southgate, and one minute to test his nerve in the penalty shootout in the final.

There is a deep dichotomy to all this. Southgate is in the process of restoring the Football Association’s image abroad as the home for sporting gentlemen. He plays by the rules and he embraces, guides the modern media.

But, at this hurdle, this missed opportunity, he is in danger of being a nearly man. His personal values are beyond criticism, but can he develop this core of gifted but callow players to actually win the events they are so close to touching?

It is well known that Southgate will study anything and everything, including techniques used by North American gridiron coaches, to try to get that extra edge through the set pieces that can decide a football contest.

However, the development that is putting English football back on the world map is the truly global aspect of the Premier League.

Nowhere in Europe, or anywhere else on earth, pays footballers more to play, and to win. The oligarchs, the sheikhs, the business entrepreneurs from Russia to Arabia to the American and Asian business giants who are smitten by the game in England (and the power of its global television appeal) knew decades ago that England was the playground but foreign influence was required.

Arsenal, with Arsène Wenger, was the first to teach a more subtle game than the high ball of English play. Wenger changed the eating habits, the sleeping habits, the lifestyle of the players – and crucially won. And now there is Pep Guardiola at Man City, Jürgen Klopp at Liverpool, Thomas Tuchel at Chelsea, Marcelo Bielsa at Leeds.

There have been Guus Hiddink, Rafa Benitez, Claudio Ranieri, Claudio Ranieri and – for better, for worse – José Mourinho hopping around the top of the English pyramid. Reaping their fortunes, changing the game, the tactics, the daily demands on players who pass through and in turn reap their rewards.

The imprint has changed, and keeps on changing. But the young English players who have to fight to represent, at best, a quarter of the lineups of the “English” clubs, must adapt or perish.

The gifted can, for a couple of years, do what Sancho and Bellingham and others did: Take their chances and further their awareness abroad before coming home better prepared for the right to play.

Or they can put all their heavily subsidised youth academy training to use with the club they sign up for as schoolboys. Foden stayed at City until his sheer tenacity, as well as his obvious giftedness, persuaded Guardiola that he was more than a token of Mancunian (Stockport, actually) talent. Sancho quit that same environment and fast-tracked himself through the Dortmund youth factory approach.

Ultimately it is for Southgate, or someone else, to persuade them to be winners for country as well as club. He is so honest, he will analyse and accept that the golden opportunity evaporated on home soil. The final ingredient must be to dare to attack.