FLORENCE HALLETT on the understanding offered by a new book and exhibition which focus on Henri Matisse’s interest in the written word and gives an insight into his controversial wartime experiences

In an interview in 1941, Henri Matisse (1869-1954) recalled the first canvas he ever painted. It was a still life of his law books, made some 50 years earlier when he had been a lawyer’s clerk, his mother having encouraged him to take up painting while he recovered from appendicitis. On rediscovering the fledgling work in his parents’ attic, he said, “I was surprised to find in that canvas, everything I had done since”.

Throughout his career, books and the written word provided Matisse with inspiration, and a conceptual armature around which to form his ideas and practice, culminating in the eight livres d’artiste – artist’s books – made in the last decades of his life. These are the subject of a new study, Matisse: The Books by writer and translator Louise Rogers Lalaurie, whose illuminating contextual and interpretative essays accompany reproductions of substantial portions of each book, including their texts.

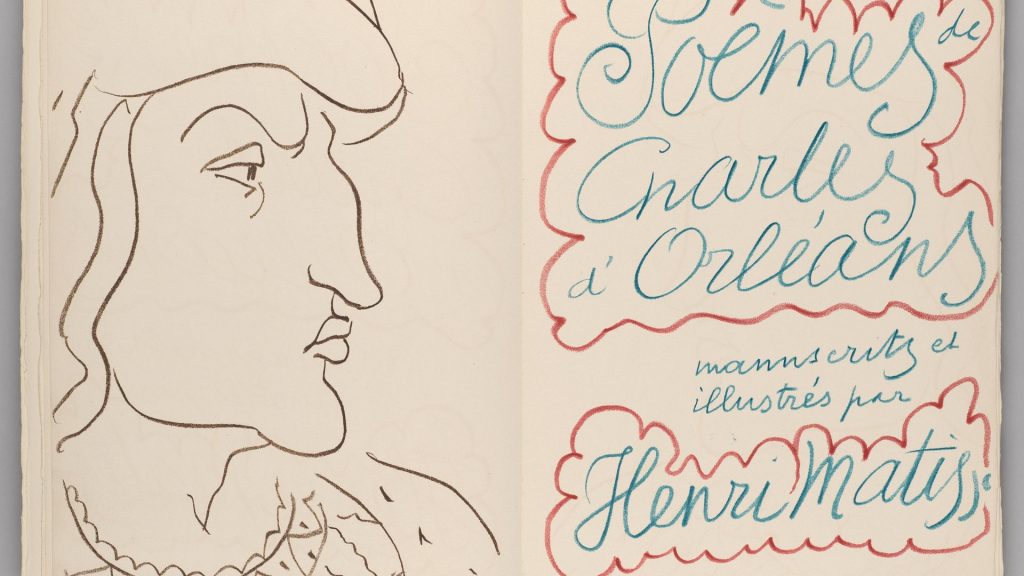

In his books, Matisse responds to texts ranging from the 15th century courtly poems of Charles d’Orleans, to Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal of 1857, and the love letters of the 17th century Portuguese nun Mariana Alcoforado.

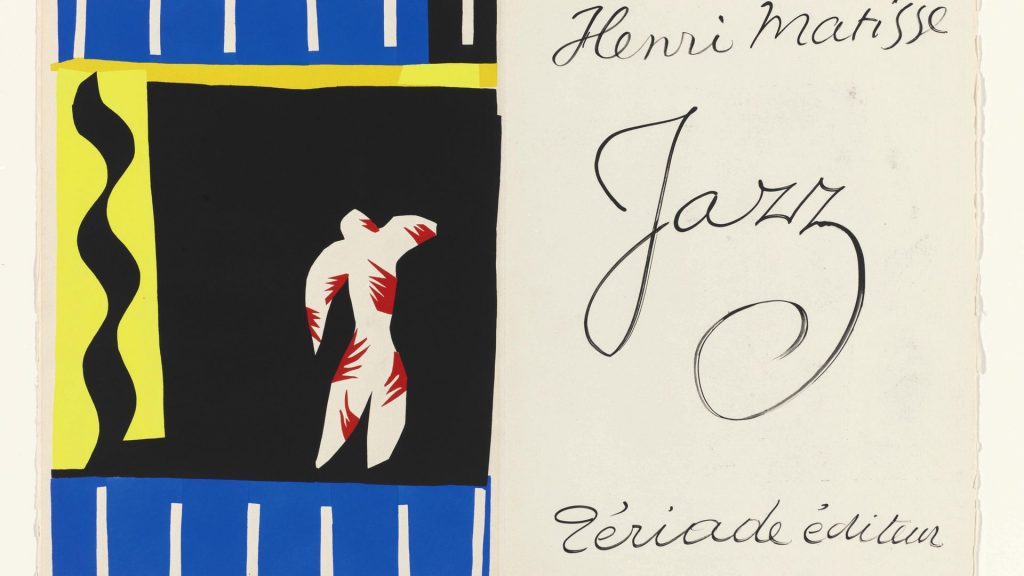

For Jazz (1947), his last and most famous book, he wrote his own text: in it he dismisses his words as “purely visual”, while simultaneously inviting us, Lalaurie explains, “to distrust what we see”, in a text that turns out to be much more than “merely an accompaniment to my colours”.

Though the books contain many familiar images, their original contexts as part of larger series of images and texts is often forgotten. As works of art in themselves, the books were printed in small numbers and are rarely seen by the public, having been dismantled and sold as individual sheets, or absorbed into private collections and obscure specialist libraries.

For Lalaurie, the books are the much neglected key to Matisse’s entire output; though all but one were made during the war years, they connect not only to each other, but to the overall shape of the artist’s long and productive career.

Together they amount to a sustained and transformative study of writing and drawing, word and image, in which Matisse developed ideas that resonate throughout his work, finding joyous resolution in the large-scale creations of his final years.

Several of the livres d’artiste make a rare appearance at the Pompidou Centre in Paris this winter, in a major exhibition delayed by Covid-19, but organised to mark the 150th anniversary of the artist’s birth. Called Matisse, Comme un Roman (‘like a novel’), the exhibition’s title is inspired by the biography of the artist by his friend, the surrealist poet Louis Aragon.

Published in 1971, Henri Matisse, roman is based on the author’s conversations with the artist, and resembles, writes Aragon, “the pins scattered from an overturned box”. The exhibition takes a similarly exploratory approach, with the words of Aragon and seven other writers, including Charles Lewis Hind, Georges Duthuit, Clement Greenberg and Matisse himself, providing the focus for each of the exhibition’s nine chronological ‘chapters’.

The exhibition comprises more than 230 works, drawn principally from the rich holdings of the Musée National d’Art Moderne at the Pompidou Centre, with further loans from public and private collections in France and abroad. In a comprehensive overview of the artist’s career, the exhibition shows how language and literature permeated his thinking even before he embarked on the overtly literary projects of his later years.

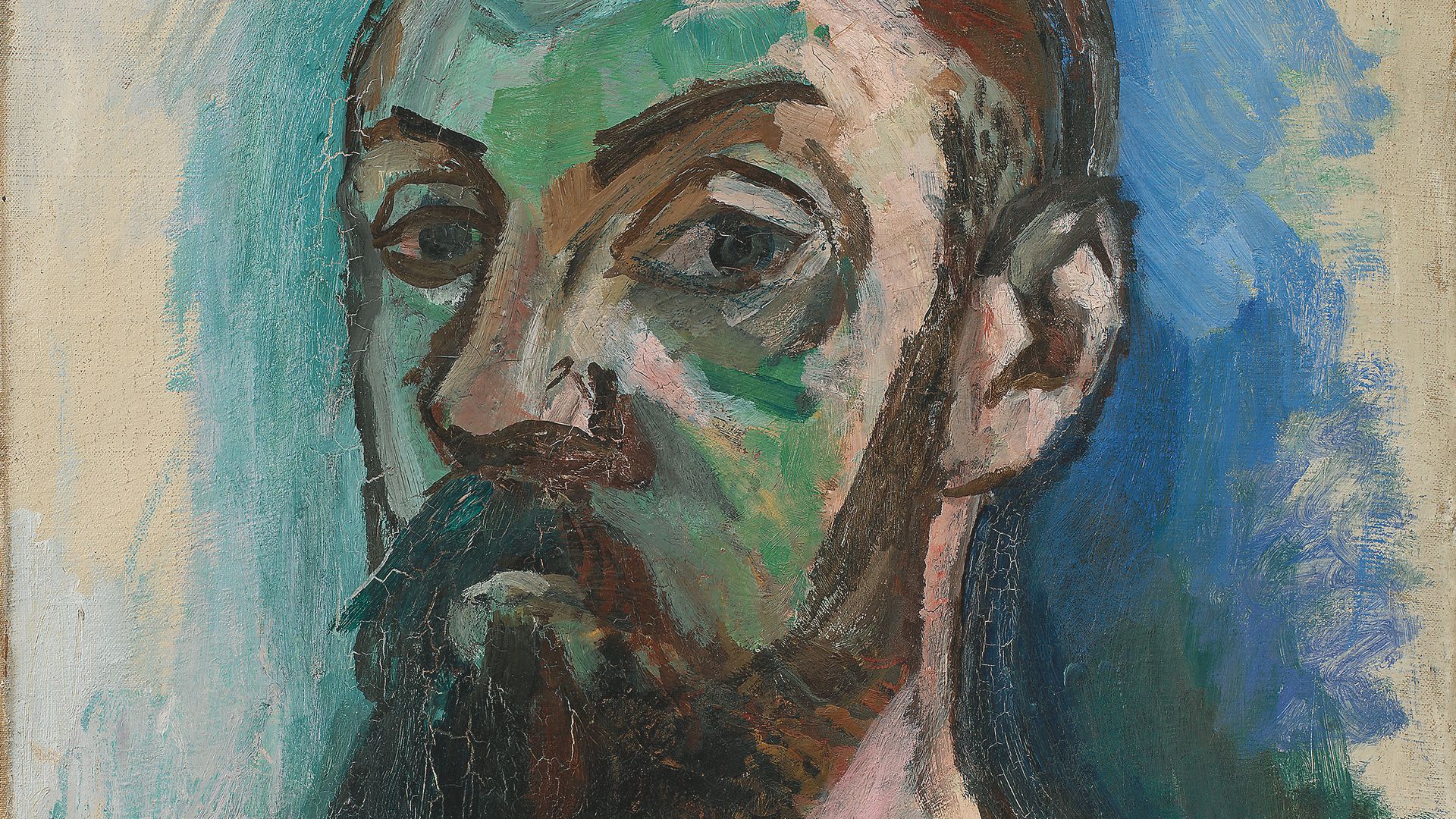

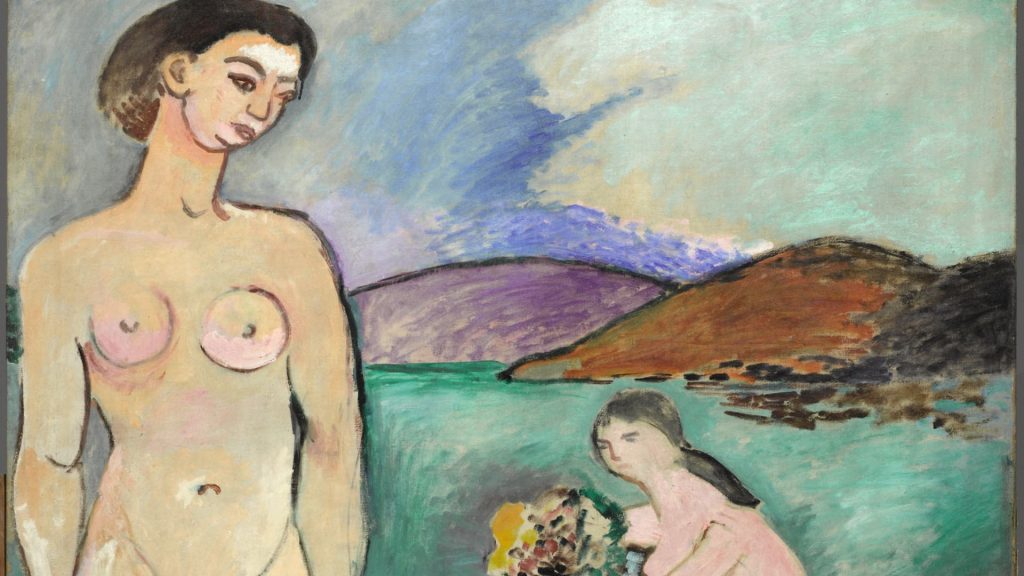

As a student in Paris in the 1890s, Matisse was well aware of the ways in which the language of painting itself was being challenged and renewed. He adopted and then rejected the radical colour experiments of neo-impressionism, and the violently unfettered, non-naturalistic colour that followed in works like Self Portrait (1906), sought to liberate colour from the service of verisimilitude, to make it a vehicle for expression.

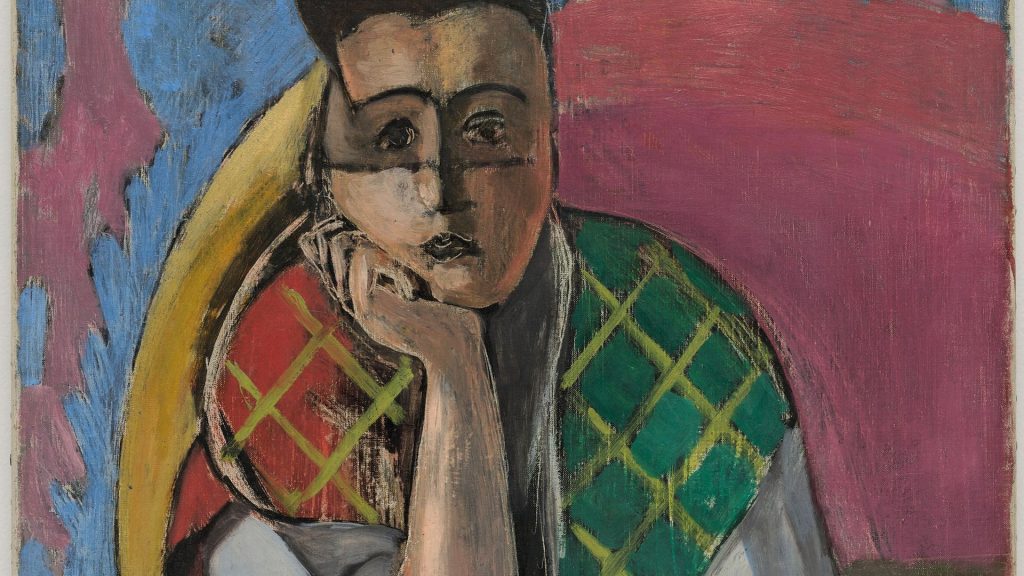

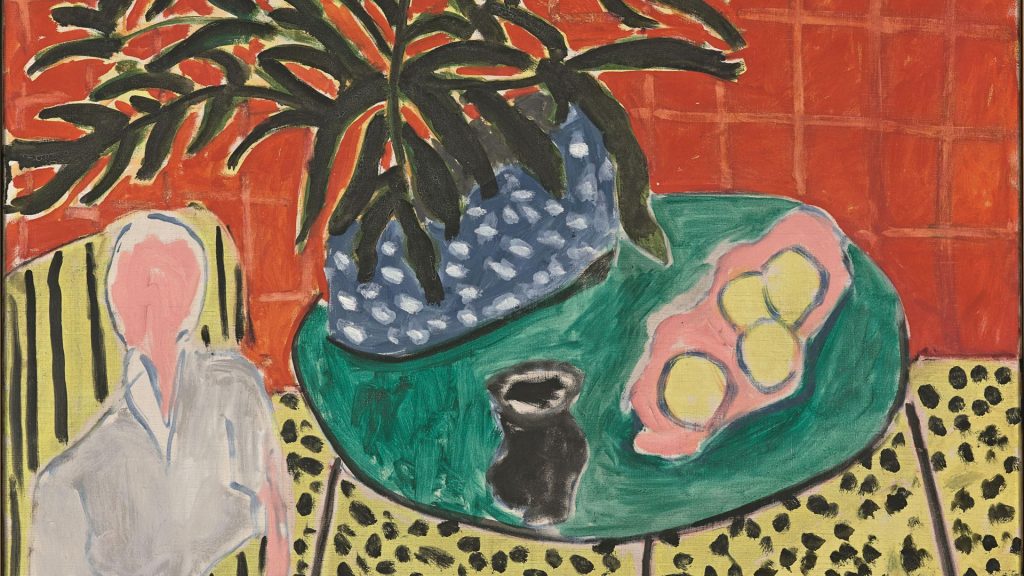

Matisse would go through several distinct stylistic phases, but his principal aims remained unchanged. “Balance, purity, and serenity,” were his watchwords, as applicable to the gorgeously chromatic “symphonic interiors” of 1911, as to the minimal, but fulsomely expressive lines of the monochrome livres d’artiste. Matisse often combines an illusion of endlessly unfolding space with the contradictory sensation of extreme flatness. In Still Life with Aubergines (1911) we are simultaneously drawn into the painting and pushed back into our own reality, creating an illusion of continuous space.

The books are similarly immersive, with images flowing from one page to another, and a tactile dimension that is recaptured to some extent in the handling of Lalaurie’s beautifully designed and produced volume. For Matisse, “the role of all decorative painting is to enlarge surfaces”, a tendency that, according to Lalaurie and Aurélie Verdier, curator of the exhibition at the Pompidou Centre, links the books to the large-scale decorative schemes of his final years.

The simple flattened forms so characteristic of Matisse’s late works were born out of his drive to discover the “essential character of things”. Time and again, he returns to particular objects and motifs, drawing and arranging them over and again. He compared his prized collection of objects to a company of actors, saying: “A good actor can have a part in ten different plays; an object can play a role in ten different pictures”.

Through repetition came simplification, and from the 1930s, Matisse increasingly saw objects as signs, that when placed in a composition acquire and confer meaning much like words in a sentence.

Drawing was essential to this process, and “plastic writing”, as he called it, provided him with a direct conduit through which to channel his thoughts and emotions. This sensitivity of response suffuses his first livre d’artiste, his illustrations for the Poésies de Stéphane Mallarmé (1930-32) etched in lines that, writes Lalaurie, replicate almost exactly the poet’s “allusive, cumulative ‘word-clouds’, sustained by almost hypnotically regular metre and rhyme schemes within which meanings cohere”. More than accompaniments, Matisse’s responses are more like musical settings – “like a descant to the text, or a figured bass”, says Lalaurie.

When Louis Aragon met Matisse for the first time in 1941, drawing had also become a matter of practicality for the invalid artist, recuperating from life-saving surgery in his apartment high above Nice. Propped up in bed, he worked on his second book, Dessins, Thèmes et Variations (1941-43), a remarkable projection of the artist’s interior world, its sensual repetitions of beautiful women and richly embellished objects in ever-shifting arrangements and viewpoints creating what Matisse described as “a motion picture film of the feelings of an artist”.

Such decadent escapism did Matisse no favours, and though he was denounced as degenerate by the Nazis, his decision to live in Vichy France – the collaborationist administration set up by Marshal Philippe Pétain – brought scrutiny of his political allegiances.

Lalaurie argues that Dessins, Thèmes et Variations was no retreat, and that the seven books produced by Matisse during the war years amounted to an act of creative resistance and self-examination, following a period of personal trauma compounded by the war.

Matisse had moved to Nice in 1917, but was visiting Paris when news came of the imminent Nazi invasion, and he fled to the south with his mistress and assistant, Lydia Delectorskaya. Delectorskaya had attempted suicide in 1939, the year that his marriage officially ended, and in 1941 Matisse was diagnosed with duodenal cancer.

Matisse’s wife and daughter had joined the Resistance, and Lalaurie writes that he was “terrified for his scattered family, and was himself recovering from a brush with death due to sepsis and a pulmonary embolism following his operation”. During the war, Matisse “was working through some very private processes”, she explains. “He was famously insomniac, so the books filled his sleepless nights.”

Aragon’s accompanying essay gives the book a sharply subversive edge: Aragon was a member of the Resistance, and banned from publication by the Nazis and the Vichy government, so that his draft needed to be smuggled to Matisse for approval. “In the darkest of the night, they will say, he drew these drawings, filled with light,” wrote Aragon, his humorous title, Matisse-en-France, insisting on the artist’s “Frenchness”, and his unequivocal opposition to the Nazis and the Vichy government.

The trauma of war surfaces again in Jazz, but then resolves as vividly depicted memories of the circus, laced with implied violence, give way to abstract representations of tropical lagoons. The book marks the beginning of Matisse’s “second life”, the extraordinary burst of creativity that followed his hospitalisation, and is his first major work to use the cut paper technique that would define his last decade.

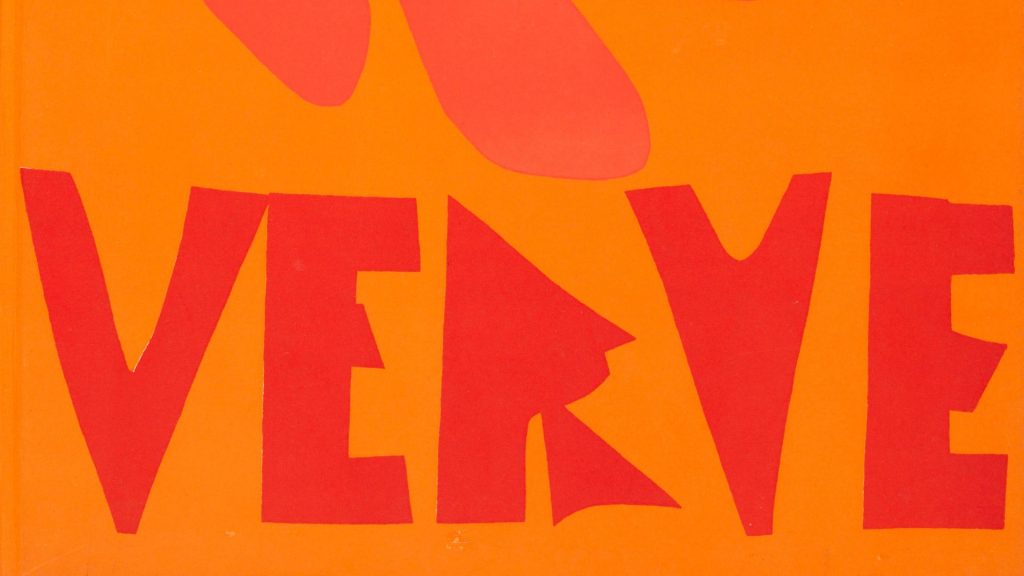

Even so, Lalaurie shows that like so much of Matisse’s work, Jazz had its roots further back in the past. The circus theme had appeared a decade earlier in his illustrations for Mallarmé, and at about the same time he had begun using paper cut-outs in his design for a mural at the Barnes Foundation, New York. More recently, a series of covers for Verve magazine had provided the immediate catalyst for the book.

Matisse described his method of cutting out paper shapes as “drawing with scissors”; it allowed him to work at once in colour and line, and could be adapted to large scale as well as small. Confined to his apartment, Matisse fashioned a garden of cut-out birds and flowers, creating a total work of art matched only by his last major commission, the Chapel of the Rosary, Vence (1948–51).

He designed every aspect of the interior, including the furnishings, vestments, altarcloths and stained glass: he called it his masterpiece, and likened it to an open book.

Matisse: The Books by Louise Rogers Lalaurie is published by Thames & Hudson £65

Matisse, Like a Novel is at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, until February 22