Forty years on, the circumstances surrounding the shooting of Pope John Paul II remain as murky as ever. Roger Domeneghetti assesses the so-called ‘Bulgarian Connection’

Just before 5pm on the afternoon of May 13, 1981, Pope John Paul II stepped into his open-topped ‘Popemobile’ ready to take a short, but slow journey around St Peter’s Square.

The sun-drenched plaza was packed with thousands of cheering worshippers in festive mood, all hoping for a glimpse, or perhaps even a touch, of the Holy Father before his weekly open-air audience.

At 5.19pm, the Pontiff’s white vehicle slowed almost to a halt as he spoke to members of the crowd, clutching their hands. Suddenly four shots rang out. An expanding crimson stain appeared on the Pope’s white silk vestments as he slumped into the arms of his private secretary Stanislaw Dziwisz. All four bullets had found their target. Two lodged in the Pope’s abdomen, narrowly missing his spine, kidneys, liver and vital blood vessels. The other two injured his left hand and right arm before also hitting two bystanders, wounding them but not fatally.

Those in the crowd close to the scene shouted “Hanno sparato il Papa!” (“They’ve shot the Pope!”), their panic and distress quickly washing through the rest of those present. The gunman, a young Turk Mehmet Ali Ağca was chased by Camillo Cibin, the Vatican’s head of security, until he was wrestled to the ground by a group of worshippers, which included a nun.

The Popemobile’s driver accelerated back into the Vatican before the Pontiff was then rushed by ambulance to Rome’s Gemelli University Hospital. He underwent four hours’ surgery to remove the bullets in his body and required numerous transfusions to replace the five pints of blood he had lost. Just before he went into the operating theatre, he reportedly asked a nurse “how could they do it?”

The operation was successful, and due to the Pope’s good health, he was able to recover quickly. The following day he took Communion in his hospital room. Another three days later, he was able to record mass, in which he forgave Ağca (“that brother of ours who shot me”), which was played to crowds in St Peter’s Square, many cheering, many others shedding tears of relief.

The shooting came just 44 days after the attempt on the life of Ronald Reagan, the recently elected US president, by John Hinkley, and less than six months after the murder of John Lennon by Mark Chapman. However, the idea that Ağca was a deranged loner was quickly dismissed.

He was a member of the Grey Wolves, a Turkish neo-fascist terror group and two years earlier had threatened to kill the Pope during his visit to the country in late 1979 in revenge for the attack on the Grand Mosque of Mecca. In a letter to Milliyet, an independent Turkish newspaper detailing his intentions, Ağca also labelled the Pontiff “the Crusader commander”. At the time, the 23-year-old was on the run after having been convicted in absentia of the murder of Abdi Ipekçi, the paper’s popular editor-in-chief, earlier the same year.

Following his arrest for Ipekçi’s murder, Ağca claimed responsibility saying he did so because he was “against the established order”. When pressed as to whether his political allegiances lay to the left or right, he denied links to either, instead saying: “I have created a terror all of my own”. While awaiting trial, Ağca recanted his claims before escaping from the high-security military prison where he was being held simply by walking out wearing a soldier’s uniform. The ease of his escape fed rumours that he had significant high-level help.

Thus, in the immediate aftermath of the attempt on the Pope’s life, most media theorising suggested that the roots of the shooting lay in the network of Turkish neo-fascists of which Ağca was a part. However, a year later, Ağca claimed he had been recruited by three Bulgarians living in Rome. In an era when everything was observed through the prism of the Cold War, this was fuel for anti-communist fire. The so called “Bulgarian Connection” was born.

With a name that seemed to have been lifted from the cover of a spy novel, the theory alleged that the Kremlin ordered the killing of the Pope either to destabilise Turkey and Nato or undermine the burgeoning anti-communist Solidarity movement in his home country Poland. Using their acolytes in the Bulgarian secret police to recruit Ağca and his supposed fascist accomplices gave the Soviets plausible deniability.

The Pope was a feared figure among those in the communist hierarchy. The Polish secret police had a file on him dating back to the late 1960s, when he was known as Karol Wojtyla, which noted that he “has not, so far, engaged in open anti-state activity”. When detailing his meetings with KGB generals after the collapse of communism in 1990, the American journalist Eric Margolis wrote that “the Vatican and the Pope above all was regarded as their number one, most dangerous enemy in the world”.

Indeed, Yuri Andropov, who was head of the KGB when the papal conclave chose Wojtyla to become Pope John Paul II in 1978, was convinced that the decision was engineered by western security services to destabilise the Soviet Union and its influence in the east.

Andropov’s paranoia may seem fanciful, but John Paul II was a staunch supporter of Poland’s Solidarity movement. In June 1979 when he visited the country for the first time since he had become Pope, it came to a virtual standstill, the state’s power emasculated. Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet general secretary at the time, contacted Edward Gierek, leader of the Polish United Workers’ Party, asking him to get the Pope to cancel his visit. Gierek refused. “Do as you wish,” replied Brezhnev. “But be careful you don’t regret it later.”

Clearly many politicians and factors played a part in the fall of communism, including Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, and the impact of years of economic stagnation which left Soviet populations hankering for change. Yet, Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet leader responsible for Glasnost, acknowledged the crucial role Pope John Paul II played, saying in a 1992 article in La Stampa: “All that has happened in Eastern Europe over these last few years would have been impossible without the presence of this Pope.”

However, beyond Ağca’s claims, the evidence supporting the Bulgarian Connection was at best circumstantial.

Predictably, it was immediately dismissed by both the Bulgarians and the Soviets, but it also had many detractors in the West, who argued that it was little more than disinformation. Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman used the event and the media narratives built around it as a chapter-long exemplary case study in their critique of the mass media, Manufacturing Consent.

The two journalists touting the Bulgarian Connection most fervently both had a history as right-wing propagandists. Claire Sterling was a self-proclaimed terrorism ‘expert’, whose critics accused her of simply taking for granted the information provided to her by western intelligence sources, many of whom remained unnamed. Paul Henze, was a former CIA station chief in Turkey and national security adviser to president Carter.

The pair drew out their theory first in articles, then books and tours of numerous television news studios. They insisted that no one who supported the opposing view be allowed on air at the same time, a request that was more often than not received positively, allowing them to dominate and monopolise coverage of the story. For a time, in the American media at least, it was almost impossible to express the opposing view, at least not without being labelled ‘unpatriotic’.

Ultimately, on the basis of Ağca’s sworn statements, three Bulgarians and five Turks, including Ağca, were charged in 1984 with conspiring to murder the Pope. The trial dragged on for 10 months, yet it was over in any meaningful sense when Ağca—the prosecution’s main witness—interrupted the first day’s proceedings to claim he was the reincarnation of Christ sent to warn of the imminent end of the world.

He subsequently changed, contradicted and retracted parts of his testimony throughout, while another witness accused agents from SISMI, the Italian intelligence agency, of coercing Ağca to implicate his fellow defendants. The case that most of the western media had confidently proclaimed to be open-and-shut collapsed, and all the defendants were acquitted.

Following Pope John Paul II’s death in 2005, the Italian parliament set up a committee to review the evidence. Its report concluded that the Soviet Union had in fact ordered the assassination. However, some members of the committee suggested the evidence was less conclusive than the report suggested. A separate report by opposition members disputed the findings. The Russians and Bulgarians issued more strongly worded denials.

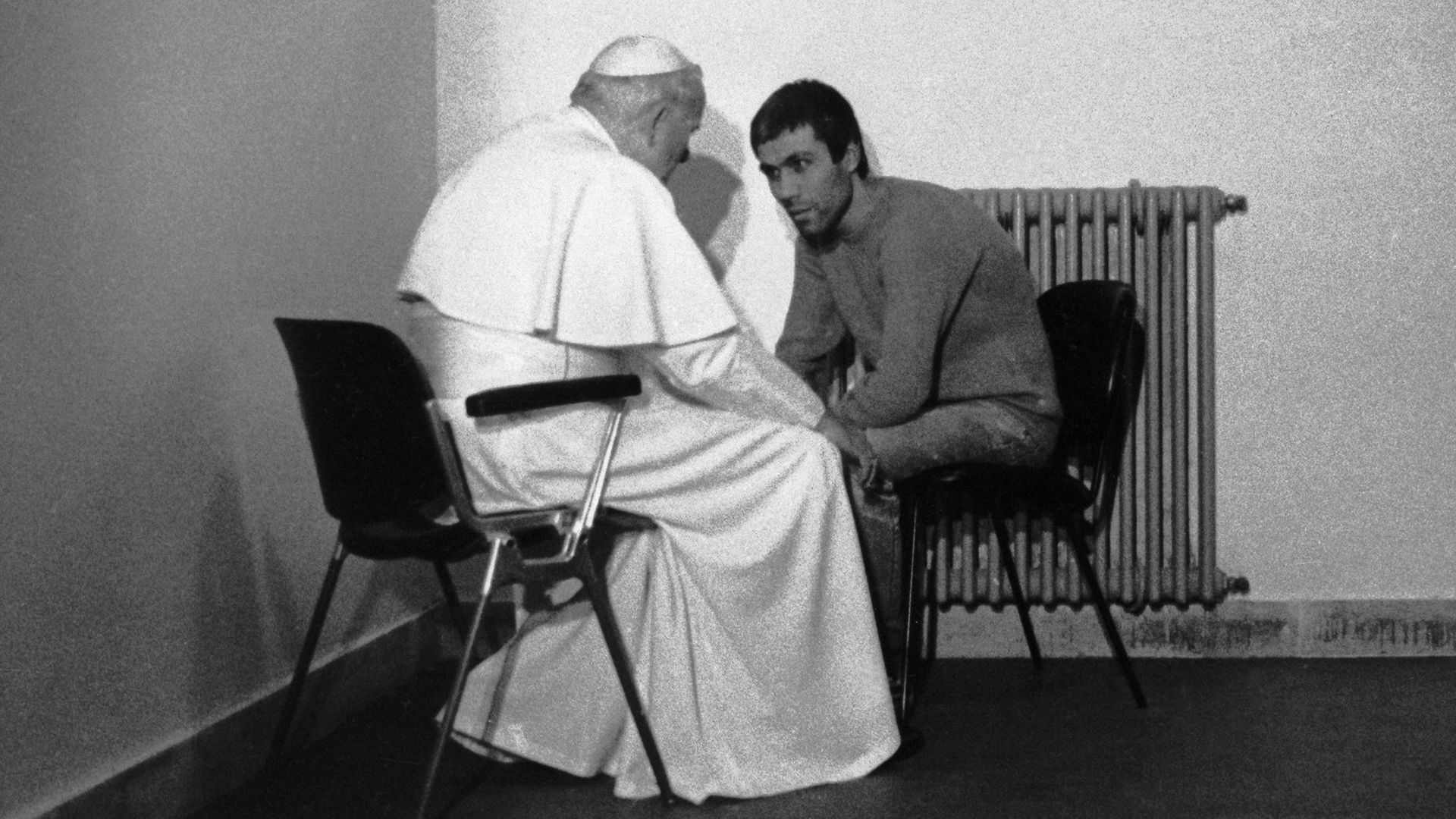

By that time, Ağca had been pardoned, largely thanks to the man he had tried to kill. In 1983, the Pope followed his quick, public forgiveness in the aftermath of the shooting by visiting his would-be assassin in jail; a meeting that was immortalised on the cover of Time magazine. In 2000, he successfully asked the then Italian president Carlo Azeglio Ciampi to grant Ağca clemency. Ağca was then deported to Turkey where he served another 10 years in jail for the murder of Ipekçi.

In the years since, he has continued to change his story about the assassination attempt on numerous occasions, making his statements on the matter utterly unreliable, some suggest deliberately so. Among those Ağca has claimed ordered the shooting are PLO, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini and even senior members of the Vatican’s clergy.

In the absence of a definitive evidence, theories about who, if anyone, Ağca was working with continue to abound. However, what people believe tends to depend on which version conforms most closely to their political allegiance.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk