The stage is supposedly set for the continent’s populist parties to sweep all before them at the forthcoming European elections. Denis MacShane is not so sure.

It has become fashionable to predict that the European parliament is about to be conquered, or at least massively infiltrated, by nationalist populist parties. A troika of hate figures for the liberal-left – Matteo Salvini, Marine Le Pen and Viktor Orban – are said to be poised to form a dominant axis in a Europe that is turning its back on Brussels’ institutions and leaders, and slowly dissolving back into a looser aggregation of nation states.

As Paul Mason put it in the New Statesman recently, ‘With nationalist, anti-immigrant populism ascendant, EU politics is about to swing to the dark side’. Guy Verhofstadt, the former Belgian prime minister and leader of the liberal group in the European parliament, has warned of a ‘nationalist nightmare’ and that May’s European elections are the ‘last chance’ to fight populism.

Brexit is cited for evidence of this, along with recent electoral gains by the AfD, in Germany, and the Franco-nostalgics of Vox, in Spain, as well as the open declaration of political war between Emmanuel Macron, the champion of European integration, and the leaders of Italy’s two ruling populist parties. The European project – we are told – is imperilled.

But is this so? Political prophesies are rarely spot on, and there are signs that the predictions of Brussels’ demise are greatly exaggerated.

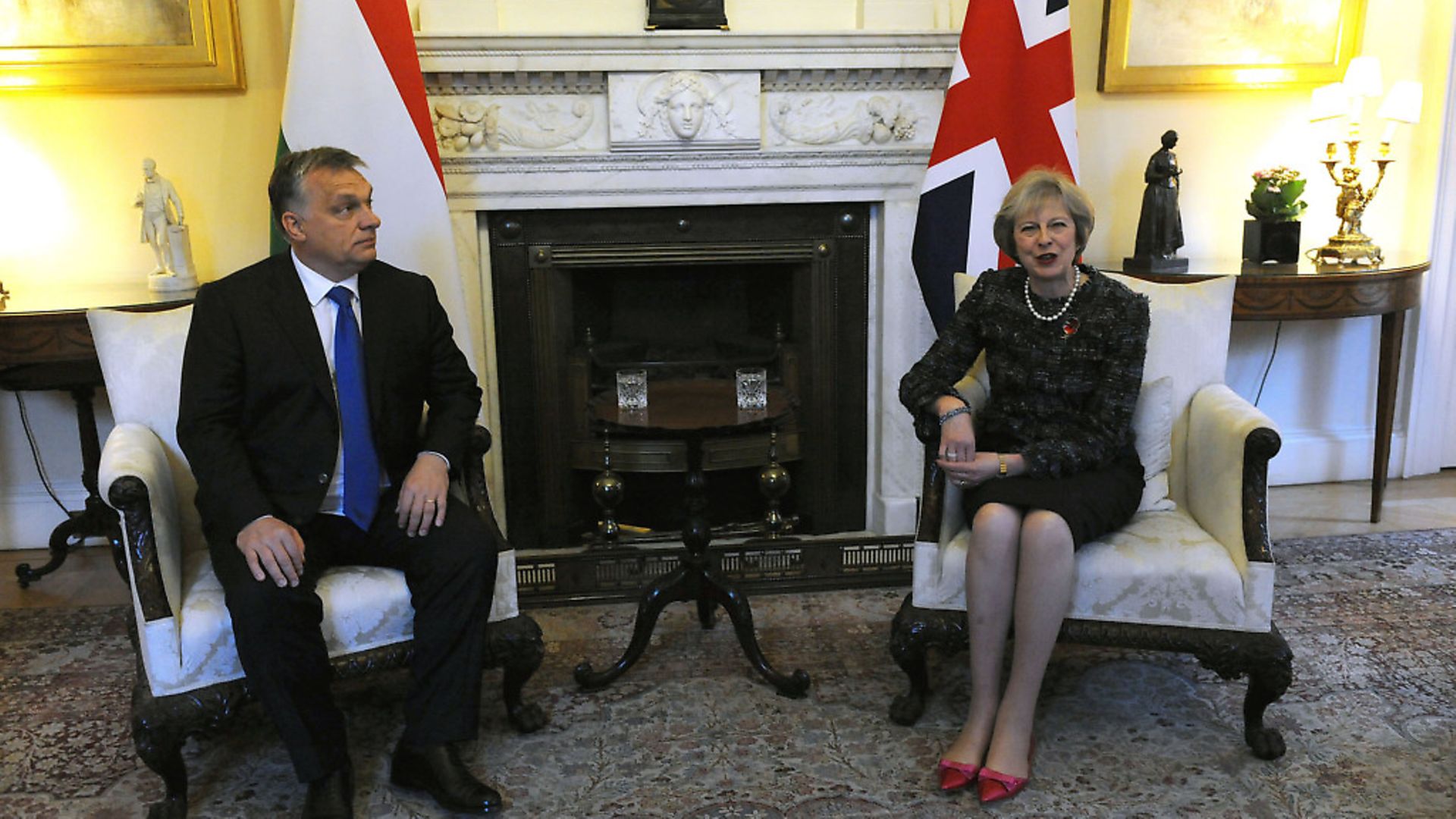

Orban is the most established of the politicians supposedly wielding the wrecking ball. Yet the last thing the Hungarian prime minister wants to do is damage his country’s relationship with the EU – the main source of its economic modernisation.

Sweden’s Left Party – formerly the Communist Party – has just announced that it is dropping its 25-year-old call for a Swexit referendum. The parties of Le Pen and Salvini have also relegated their calls to quit the euro or hold plebiscites on leaving the EU.

The primary reason for this is the Brexit effect. Europeans of all political persuasions have looked with shock and awe at what Britain’s 2016 referendum has done to the country’s politics and economics. For any party to advocate anything remotely similar in their own nation is a stone cold, guaranteed vote-destroyer.

For sure, there is a vibrant strain of nationalist, identity politics emerging on the right across Europe. But leaving the EU is not a part of it. All are united on that. For that, at least, we have Brexit to thank.

In other respects, the new right is strikingly disunited – not a helpful characteristic for a movement said to be mounting a takeover. Salvini and Le Pen might like to flirt with Vladimir Putin – who, of course, is happy to reciprocate, as part of his strategy to enfeeble the EU. Yet the senior of Europe’s nationalist authoritarian populist parties is PiS, Poland’s ruling party, which is fanatically anti-Russian.

Meanwhile, Austrian and German rightists have no interest in helping Salvini in his quest for richer countries north of the Alps to take in more refugees and economic migrants fleeing across the Mediterranean.

The European Union is, at heart, a project for tackling problems in a supranational way. For parties that see their nation’s problems through a narrow, national prism the EU will have severe limitations as a vehicle for advancing their agenda.

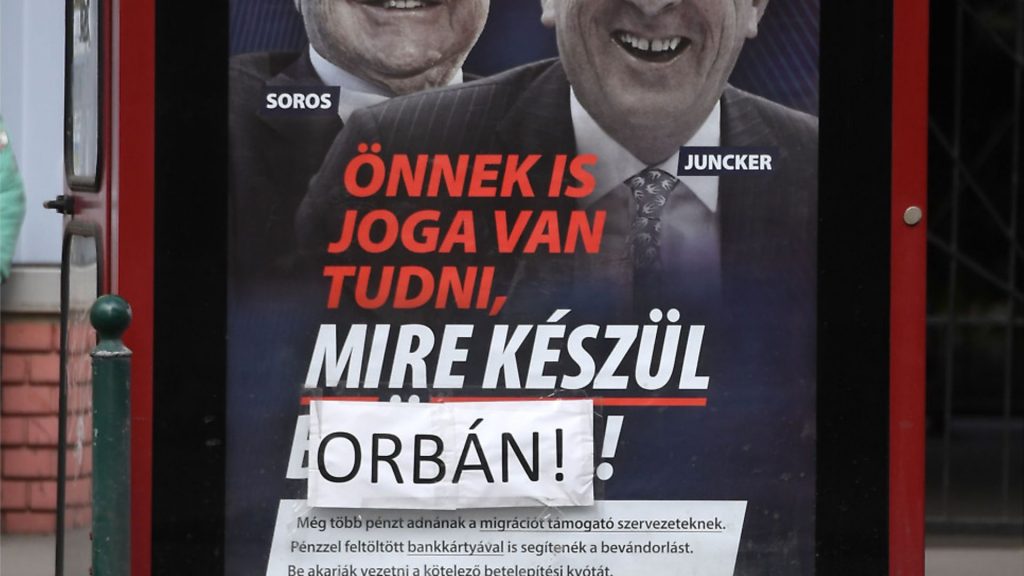

One supranational characteristic that does seem to increasingly define this emerging strain of populist politics, though, is anti-Semitism – often characterised by shameless denunciations across the continent of George Soros, as a proxy for Brussels, the establishment and any other scapegoat that people can be encouraged to think of.

Anti-Semitism has also surfaced in the gilets jaunes movement in France, where Jewish cemeteries have been desecrated and a leading intellectual and member of the Académie française, Alain Finkielkraut was attacked in the streets as a ‘dirty Zionist shit’.

Yet the gilets jaunes’ increasingly ugly political extremism is turning off mainstream voters. Since December, Macron has been recovering in the polls. French voters may dislike his style and sympathise with some of the economic demands of the protestors, but they are not going to back openly racist and anti-Semitic politics.

And there are, of course, other places for the voters to go than the populist right. While it is perfectly fair to note that the era of 20th century dominance by broad-based centre-left and centre-right parties is over, the new parties benefitting from this change are not all on the right. Syriza, in Greece, Podemos, in Spain, and Die Linke, in Germany, get less attention in the British press than their rightist counterparts, but are no less significant in this new political era for the continent. All want more taxes, more public spending or a universal basic income.

The ‘mainstream’ parties of the left are also moving this way. Italy’s Partito Democratico, the main centre left party formed from the europhile communists and old democratic socialists, has elected a new leader and ditched the heritage of Matteo Renzi. In Germany, the Social Democrats have also moved left.

Meanwhile, the liberals in the middle are being over-taken by the (stridently pro-EU) Greens, increasingly attracting young voters for whom climate change, the destruction of the environment and dislike for the Davos elites are growing themes.

All this means that, with the disappearance of UKIP from the European parliament, May’s elections will not lead to an increase in anti-European MEPs. Nor will it end with a Le Pen-Salvini ascendancy in Strasbourg, with Macron’s MEPs, plus an estimated 50 Greens and increased representation from parties like Syriza or Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise providing a majority against it.

Macron had hoped to create a genuine trans-national list of MEP candidate for reform of the EU to take the place of the departing British MEPs. But the old guard in the European parliament who don’t like his overthrow of traditional parties in France blocked the initiative. So while Macron’s La République En Marche! party will get its share of MEPs – about 20 – they are not strong enough to make a difference other than probably to reinforce the ALDE liberal group, even if Macron is no fan of its headline-hunting leader Verhofstadt.

The elections will, of course, be a test for Macronism, as much as it will be the populists. In his recent letter published in 28 EU capitals, the French president dropped the aggressive, centrist liberalism that characterised his earliest days in office and moved to arguing for a ‘social shield’ for European workers and unions, along with tougher controls on immigration and a crackdown on the money flowing in from the US and Russia to back interference in domestic elections.

His concept of a Europe that protects, rather than a Europe that exposes the poor to the excesses of finance capitalism, may be a tactical response to the gilets jaunes protests, but it places Macron closer to the traditional centre-left, rather than ultra-liberal Davos-man capitalism. It also provides a secure bulwark against those restive forces on the right.

Macron, meanwhile, is not the only one coming under pressure for a change of tack. The forces of Europe’s changing politics do not only exert themselves on those in the centre.

In Italy, where Salvini is trying to get rid of his coalition partners the Five Star Movement, a year of disastrous economic mismanagement means the country is now recording negative growth and is poised on the edge of a serious banking crisis, worse than that suffered by Greece after the 2009 crash.

The rich northern Italian capitalists have made clear to Salvini that if he expects to keep being bankrolled, he will need to drop his excessive 1930s demagogy and instead build a major right-of-centre political party to govern Italy in the interest of its bourgeoisie.

Salvini’s position also encapsulates the other difficulty facing the populist right in much of Europe. Far from being the outsiders, they are – in many countries – now the establishment. And European elections have always been a wonderful opportunity for protest, punishment votes. Where populists have found themselves in power, they are now vulnerable at the ballot box.

All these developments make it unlikely that the European parliament will fall to the populists. A fascinating poll of 1,030 UK voters in January asking how they would vote if the elections were to take place in Britain the result showed 27 Labour MEPs and 36 Conservative MEPs would be elected with UKIP down to just 10.

To be sure, these figures reflect national polling intentions and all polls on Europe-wide politics need to be handled carefully. But another recent survey in the UK reported nearly 50% have a positive view of immigration, with only 25% hostile. Is the near 20-year run by nationalist populists based on denunciations of all things Brussels and demagogic rhetoric against immigrants finally running out of steam?

The two principal vectors of anti-immigrant sentiment since 2016 have been Donald Trump and the Brexit evangelists. Neither are doing very well and the cold reality that no modern economy is producing enough children to provide today’s let alone tomorrow’s workforce especially in the health, construction, home help and old age care sectors is sinking home.

Take away anti-immigrant sentiment and the clear renunciation by Macron, Merkel and Juncker of any super-state European project and there is less and less point in voting for nationalist populist parties.

Number crunchers in the European parliament produced private estimates at the beginning of the year showing 490 seats out 705 going to established centre-right, centre-left, liberal, green and democratic left parties. Some 66 MEPs would sit as independents, not aligning with any party. The remainder would be a fissiparous assortment of the new rightist authoritarian and populist parties but without any connecting links that could create a cohesive political force to shift the European parliament as far to the right as some have been predicting.

Some have suggested that the centre-right EPP could make an alliance with the hard-right, but the European parliament does not produce coalitions to govern and many conservative parties would quit rather than be associated with the extremists.

There will be a shake up of some of the old, cosy corridor, wheeler dealers and that is no bad thing. But if there is one lesson of Brexit that has been absorbed across the EU political spectrum, it is that anti-European politics can do serious damage to a country.

Europe’s nationalist, loudmouth right gets all the attention but they are not about to conquer Europe. The continent’s new politics are actually rather more diverse – pretty green, sometimes strongly social and often quite left-wing.

Denis MacShane is the former Minister of Europe. His new book Brexternity will be published shortly