Facebook might seen like a humbled giant, right now. But make no mistake, its business model is never going to change, says PARMY OLSON. And that means people will remain products.

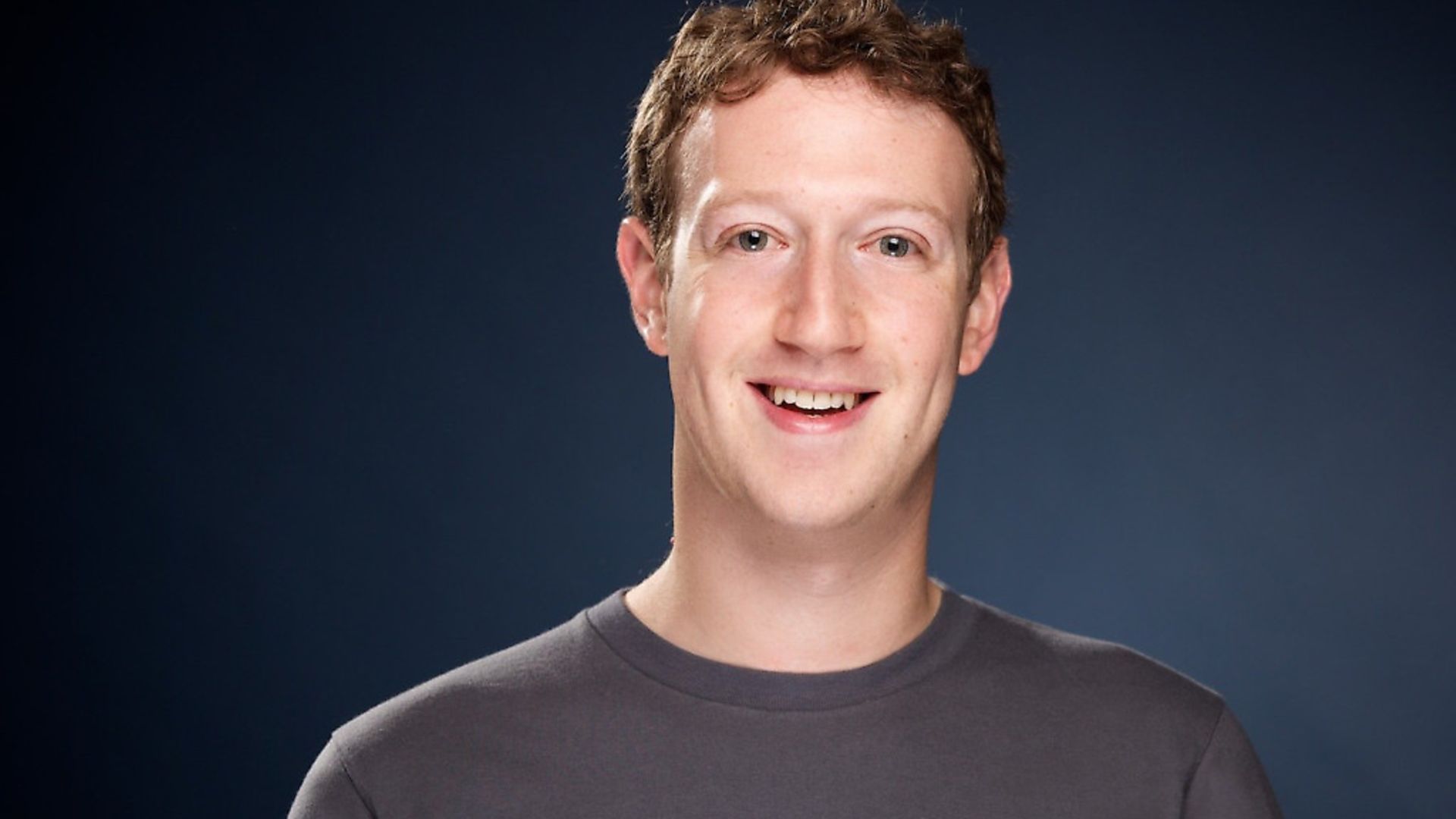

‘I started Facebook, and at the end of the day I’m responsible for what happens on our platform.’

This was the most sincere remark in Mark Zuckerberg’s lengthy statement, made in response to the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

What is surreal about this scandal, and what probably left Zuckerberg nonplussed for the first couple of days after it broke, was that Cambridge Analytica hadn’t done anything particularly new or outlandish.

Thousands of app developers have scraped our data from Facebook to help them build a profile of who we are – working mothers, geeky A-level students or pensioners who read the Daily Mail – then used that data to target us with ads.

In Silicon Valley parlance, this is referred to as ‘serving’ people ‘relevant’ content. It’s a pleasant translation of the outcome for users, which is making the internet more creepy. Ads for dog food crop up after you post on Facebook about getting a new puppy, for instance.

Sharing our data has been fundamental to Facebook’s business model since Zuckerberg dropped out of Harvard and moved to Palo Alto, California to build his company. It’s why the stock market has valued it at half a trillion dollars.

And for the past decade, Facebook’s users – who now number more than two billion – didn’t really care. We kept logging in to the site, or logging in to apps like Fitbit, Uber, or AirBNB with out Facebook details so we didn’t have to remember yet another password.

Then along came the Cambridge Analytic revelations. The world saw how the sausage really got made, and everything changed. The political analysis firm, funded by hedge fund billionaire Robert Mercer , did data-mining and marketing for Donald Trump’s presidential election and took credit for his victory, citing its psychographic profiling techniques. It might well have been bluster. The firm’s CEO, Alexander Nix – who was suspended last week – was prone to salesman-like exaggeration. He told me during an interview in March 2017, for instance, that he’d spoken to Trump strategist Steve Bannon every day for five years.

But even if Cambridge Analytica did exaggerate its impact on Trump’s win, the outrage which has followed the revelation of how easily it got so many people’s data will not subside any time soon and will be felt widely.

Various investigations are getting under way into data collection, while the hashtag #deleteFacebook has been trending on Twitter; among those to use it has been Brian Acton, one of the co-founders of Whatsapp, who sold it to Facebook four years ago for $19 billion. He shocked Silicon Valley by writing: ‘It is time to #deleteFacebook.’

Timing is certainly key in all this. Had the ex-staffer’s revelation come out a year ago, the calls to delete Facebook wouldn’t be gathering steam, and Zuckerberg’s net worth wouldn’t have dropped by $5 billion. But this all comes after a year of steady and increasing criticisms of Facebook’s inability and unwillingness to police its own platform.

When the company was criticised for letting fake news run rampant, Zuckerberg said Facebook was a technology company and not a media one, meaning it had little obligation to ensure news reports were credible.

Now also witness the company’s tone-deaf, first response to the allegations of Cambridge Analytica’s data-siphoning: ‘The claim that this is a data breach is completely false… People knowingly provided their information.’ In other words, ‘scraping data on millions of users was totally normal, and okay’.

Facebook’s argument that people ‘know what they’re doing’ on its site is completely at odds with what its open platform allows advertisers to do, which is manipulate us. Facebook made that all possible when it announced itself as a platform in 2007, launching features like Facebook Connect and the Open Graph that spread its tentacles across the internet, allowing any service or advertisers to track its users.

This is what Cambridge Analytica sought to do and, sorry everyone, what advertisers will continue to do well after the dust has settled from Zuckerberg’s latest unpleasant scandal. Facebook needs something from its users if it’s going to continue to let them use its site for free, and that’s their data. As the saying goes in technology circles, when a product is free, you’re the product.

It turned out people needed a character like Cambridge Analytica to act as a wake-up call, a spotlight on how even the most unscrupulous of firms had the potential to get our information. The question now is how many people will actually delete their Facebook accounts, or how many will simply deactivate them, allowing Zuckerberg’s company to retain their personal information until they are ready to log back on.

The Cambridge Analytica story has gone viral, but that doesn’t mean it will change attitudes for the long-term. For many people, Facebook is a single-reliable gateway for passively staying in touch with distant family and old friends – sprinkling a few likes on the News Feed so we don’t have to compose a message.

For many, the benefits will continue to outweigh the outrage over what Zuckerberg can do with our data. He has admitted that Facebook ‘made mistakes’ and he is promising substantial changes to make people more aware of how their data is being used. This is a good start, and such changes are needed. But be in no doubt that his fundamental business model, of tracking our lives and selling that information to others, is never going to change.