Were the Angry Brigade a mere comedic English counterpoint to the doomed romantics of Germany’s Baader Meinhof gang or a far more sinister, if thankfully incompetent, force?

Today anger is an emotion associated with right wing populism, of foaming keyboard warriors and the puce-faced men that are – for better or worse – often dubbed ‘gammons’.

But 50 years ago fury was emanating from the opposite end of the political spectrum. In the early 1970s an irate group of far left activists embarked on a short lived campaign of bombing that was intended to inspire the working classes to rise up and overthrow the shackles of consumer capitalism.

The Angry Brigade were the UK’s first urban guerrillas. Yet while contemporaries such as Germany’s Baader Meinhof gang and Italy’s Brigate Rosse murdered, bombed and kidnapped, posing direct challenges to their government’s ruling elites, our homegrown version killed, well, no-one.

Despite this they were taken seriously enough to be the subject of a six month long trial that commanded the media’s full attention and drew an unexpected amount of public sympathy.

The roots of the Brigade, like their more murderous European counterparts lie in the events of May 1968. The student protests had brought the French government to the brink of collapse and shown activists on the left what could be done with a little carefully-targeted provocation and disruption.

However, by the end of the decade it became clear that marching and public protest was only going to get you so far. A number of more fervent souls decided that the time had come to engage in real armed struggle.

What were they angry about? Well, their more immediate gripes included the war in Vietnam (of course), Franco’s fascist dictatorship in Spain, the treatment of women and a vague dissatisfaction with the mindlessness of modern consumer capitalism.

They hoped their actions would unsettle the British establishment and, perhaps, inspire their proletarian comrades. This was an era when, for many, the revolution seemed tantalising close, despite the fact that few were able to articulate what society would look like after such an uprising.

And while their continental cousins were deadly serious, there was a playful element to the Angry Brigade. Their name was an ironic reference to the ‘brolly brigade’ of frustrated consumers.

According to Stuart Christie, one of those acquitted in their 1972 trial, an early alternative was ‘The Red Rankers’, largely because it would have been funny to hear then-home secretary Roy Jenkins – he of the rhotic defect so beloved by TV impressionists – attempt to pronounce it.

Their first bomb went off in August 1970 at the house of Metropolitan police commissioner Sir John Waldron. Accompanying it was a letter explaining that he had been sentenced by “the revolutionary tribunal for crimes of oppression” signed by “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid”. A week later it was the turn of the attorney general, Sir Peter Rawlinson. His was accompanied by a scrawled note signed by “The Wild Bunch”.

These were the start of 23 bombings that took place over the course of the next year. After a while the Brigade decided that responsibility for their actions should be claimed in a series of communiques that explained their worldview.

These were issued using, of all things, that popular 1970s kids’ stocking filler, a John Bull printing set. “The Angry Brigade is the man or woman sitting next to you,” they threatened in Communique 9. “They have guns in their pockets and hatred in their minds. We are getting closer.”

The police were initially at a loss with how to combat this baffling new threat. “We had no idea,” remembered Roy Cremer of the Special Branch in 2002 documentary. “We couldn’t actually pinpoint the people who were doing it. Another way of tackling it would have been to work out where they would strike next. But that was even more difficult because when you looked at the targets they were so bizarrely different.” Indeed these included the house of home secretary Robert Carr, the Biba store and the 1970 Miss World contest at the Albert Hall.

It was detective chief superintendent Roy Habershon who did most of the leg work regarding the investigation. Slowly and painstakingly he made links between Situationist-inspired activists and the First of May, an explicitly anti-Franco group that had already caused a number of explosions prior to the first Angry Brigade bomb.

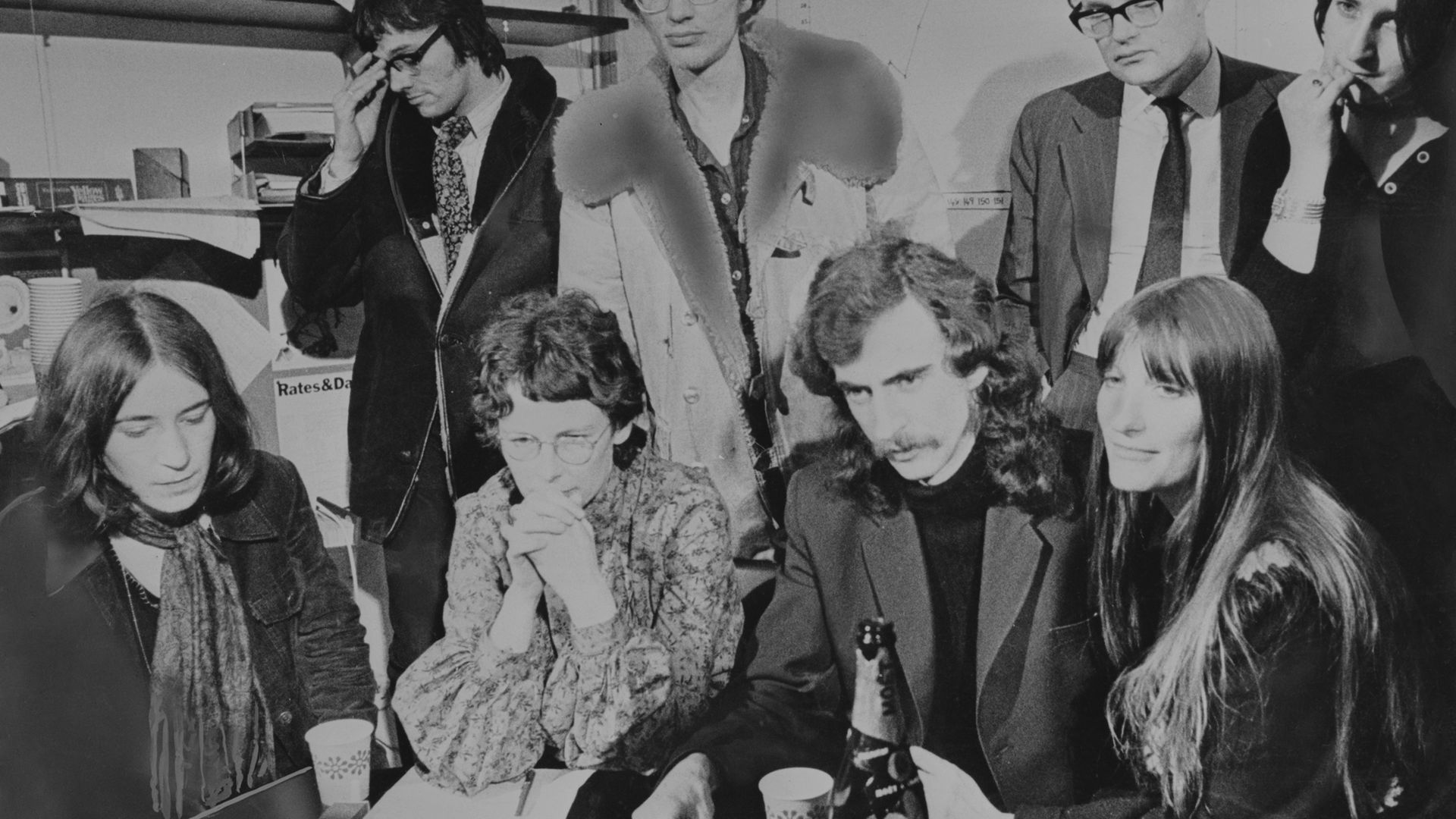

By August 1971 the police had located their quarry. Four men and four women were arrested. Half of these – John Barker, Hilary Creek, Anna Mendelson and Jim Greenfield lived in a shared house at Amhurst Road, N16. The others – Stuart Christie, Kate McLean, Angela Weir and Christopher Bott – were all involved in far left/ anarchist politics. It would be another nine months before the trial could begin.

The so-called Stoke Newington eight were largely middle class stock. John Barker and Jim Greenfield had both been to Cambridge, Hilary Creek had attended a private school in Bristol. (Ironically, the only Angry who could be described as ‘salt of the earth’ was Jake Prescott, who by this time had already been charged and sentenced to 15 years for conspiracy to cause bombings.)

None seemed intimidated by their upcoming ordeal. Mendelson and Barker even applied to have the trial postponed by two years, claiming that a fair trial was impossible given the notoriety of the Brigade at the time.

The judge, Mr Justice James turned this down, but he did allow the defence to put a list of questions to potential jurors – the idea being that the more ‘working class’ the 12 members were, in theory the more sympathetic they would be to the defendants.

Three decided to defend themselves, a smart move in that they were able to address the jury directly, and outline their political worldviews. Barker, in particular, made full use of this. Indeed his advocacy drew widespread admiration from all sides, his fellow defendant Stuart Christie describing it as “worthy of Tom Paine”.

The trial would become the longest and most expensive criminal trial of the 20th century. There were nearly 700 pieces of forensic evidence, including guns and ammunition, gelignite and detonators picked up from the Amhurst Road house (which the defendants alleged was planted).

Six of the defendants were charged with possession of these various accoutrements, but the meat of the case was the charge that all eight were conspiring together. This was far harder to prove and the prosecution struggled at times to land a punch. Any discrepancy in police evidence was thoroughly examined and challenged by the defence.

Come December 6, 1972, the jury finally delivered their verdict: they acquitted Christie, Bott, Weir and McLean and convicted the four who shared the Amhurst Road house. But only on a 10-2 majority. The jury also asked the judge, Justice Melford Stevenson, for “clemency and leniency” in his sentencing.

Stevenson duly took note and sentenced them all to 10 years rather than 15, the standard sentence for conspiracy. It was an outcome to no-one seemed particularly happy with, least of all the police, who had spent over two long years on the case.

In many ways the Angry Brigade case marked the high tide for far left activism in the UK. Today the idea that ‘propaganda of the deed’ could inspire some sort of popular revolt seems quaint, hardened as we have been by the IRA, and in the 21st century, the nihilism of Al-Qaeda and IS-linked groups.

It should be noted though that at the time much of British counterculture regarded them with a certain indulgence, even mild admiration. The underground press, from Oz and International Times to Time Out, ran largely sympathetic pieces on them. The Angry Brigade even inspired a protest song, of sorts: Hawkwind’s Urban Guerrilla, which was a minor hit in 1973.

Most of the individuals implicated in the Angry Brigade trial kept a low profile in the decades after. Anna Mendelson changed her name and published poetry. Hilary Creek returned to university and ended up in a research job abroad. None recanted their previous life although John Barker, writing in the 2000s, admitted that “some of the rhetoric and righteousness of Angry Brigade communiques now makes me cringe,” adding that “the police framed a guilty man”.

“We were libertarian communists,” he stated. “And for another we were not that serious…like a lot of young people then and now we smoked a lot of dope and spent a lot of time having a good time.”

So was that all it was – a bit of a laugh? It’s easy to dismiss the whole Angry Brigade episode as a comedic English counterpoint to the doomed romantics of Germany’s Baader Meinhof gang; more Citizen Smith than Secret Army.

However, they did achieve one thing. The formation of the Bomb Squad, now the Anti Terrorism Branch was a direct result of the Angry Brigade’s campaign. Their actions forced the authorities to up their game, which they arguably badly needed to, given the more serious challenges they would face in the decades ahead.

The Brigade’s own youthful naivety was product of another era. The revolution never arrived and in the 21st century terrorism is usually announced via a gruesome YouTube video rather than a John Bull printing set. Different times, indeed.