Boris Johnson is among those arguing that freeports will give post-Brexit Britain a boost. But, as SUNA ERDEM argues, these global curiosities come with a harmful, shady reputation.

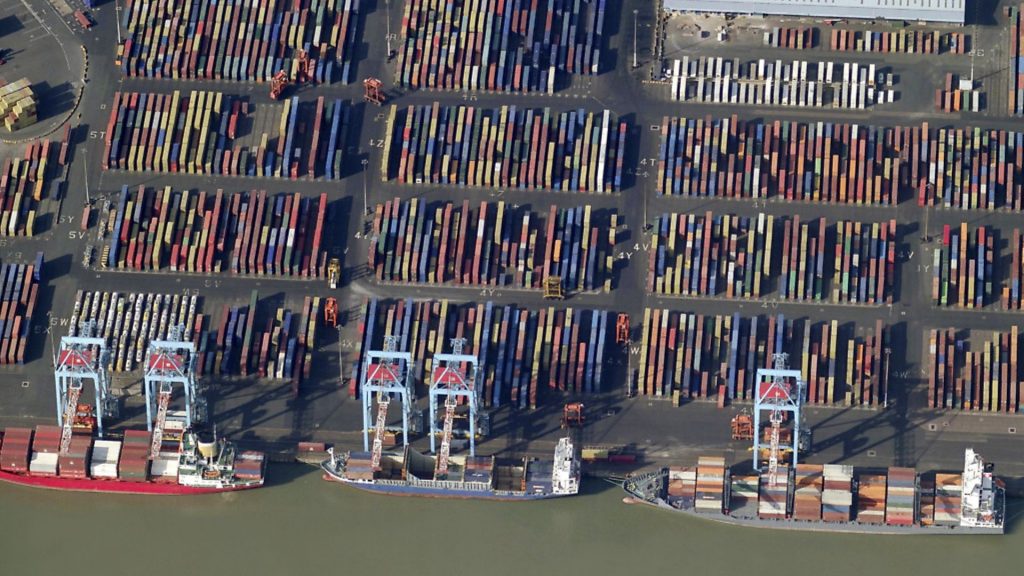

The Brexit brigade have a new toy. The latest flavour of the month is the prosaically-named but exotically-styled ‘freeport’ – essentially a special free-trade zone where the import taxes and tariffs of the host country do not apply, and which has given rise to salacious and colourful stories of shady deals and dodgy art sales. And, who knows, if Brexit ever does get sorted, one might be coming to a seaside near you.

The idea has even elicited a rare moment of clarity and consistency from the obfuscating, evasive Conservative leadership front runner Boris Johnson. Earlier this month, he announced that he was “firing the starting gun on freeports for Britain”. “Taking advantage of the opportunities afforded by leaving the EU on October 31 to introduce freeports is an excellent way to boost businesses and trade in regions that Westminster has neglected to pay attention to for too long”.

Johnson championed freeports at a hustings this month in Belfast, which he has earmarked as one of a potential six new UK sites, and again back in January at an event sponsored by JCB. It is not just Johnson interested in this concept. When asked, his rival Jeremy Hunt also suggested he could support the idea, which has long been advocated by the Tory right.

Across Britain, local politicians have already been queuing up to bid for freeport status. Ben Houchen, the excitable Conservative mayor of Tees Valley, has long wanted one in his region and has commissioned reports extolling the virtues of such a scheme.

Ross Thomson, a Scottish Conservative MP, hopes that his constituency in Aberdeen South will be chosen as a location. “Freeports can provide a huge boost to our port cities by driving economic growth, attracting investment and in a post-Brexit world supporting the UK as a truly global player,” he said.

So this is not just the latest off-the-cuff move for Johnson. It seems to have legs. The impetus has been building for some time. The argument in favour of freeports was among the libertarian ideas that appeared in Britainnia Unchained, Global Lessons for Growth and Prosperity, a sort of pro-Brexit, pro ultra-deregulation pamphlet published in 2012 by then relatively new right-wing MPs who have since gained influence, including Dominic Raab, Liz Truss and Priti Patel.

A few years later, as the Brexit debate was raging in earnest, Conservatives were fired up by a new report prepared by Richmond (Yorks) MP Rishi Sunak in 2016, advocating freeports as the way forward for Brexit Britain. His work has been supported by the likes of Michael Gove and Steve Baker. Theresa May’s erstwhile enforcer Nick Timothy was also a fan.

The Treasury has also been studying the idea, and late last year the proposals were debated in Westminster. It has also proved attractive across the political divide. During November’s debate, MPs from Labour and the SNP lobbied for the chance to set one up in their constituencies in the hope of sparking an economic revival in areas hit by recession, austerity, the loss of industries and other ills.

So why do they all think that freeports are so great? To look at the rhetoric, it’s all about boosting manufacturing and jobs. Sunak claims in his paper that freeports could create as many as 86,000 jobs for the British economy. “These would not only provide domestic manufacturers with a wealth of tangible benefits, but also send a clear message to international markets that Britain’s new global role will be open, innovative, and outward looking.”

Advocates insist that the low-tax, low regulation environment in the zones will encourage foreign investment as global companies can incorporate manufacturing facilities at a low cost and great convenience into their supply chains. Sunak claims that as many as 86,000 jobs could be created for the British economy. Local employment will be improved by the increased activity in the zone in their midst, they say.

Houchen commissioned consultants Mace Group to produce a report, which maintained they would help depressed parts of the country in a scenario that encompassed a network of freeports based in locations such as Grimsby, Hull, Teesport and Hartlepool.

Road, rail and network infrastructure would be improved, Mace said, helping produce an additional £70 billion in GDP and the British economy would be “rebalanced” by increasing productivity in the north of England. This is one reason cited by former chancellor George Osborne for his support. Mace estimated that double the number of jobs cited by Sunak could be created.

On the face of it, then, freeports are A Good Thing.

However, these claims have been seen as overoptimistic at best. Sunak’s numbers are simply based on a calculation involving the number of jobs in freeports – or freezones as they are also known – in the US, adjusted for the size of the UK workforce.

They don’t appear to take into account UK conditions or the type of freeport that might be created, and there is no guarantee that they will be realised. In fact, they could simply deprive other regions of jobs – other regions in which manufacturing and jobs are generating tax.

“It is by no means clear that (free zones) would lead to new manufacturing investment,” wrote Catherine Barnard, professor of EU law at Cambridge University, in an analysis for the think tank UK in a Changing Europe. “There is a risk that exporting and importing firms could simply relocate to within the UK to reap tax advantages without increasing manufacturing capacity.”

And if there are jobs, of what kind? There are around 3,000 freeports around the world, but the one that has been the cause of much Brexiteer excitement is Jebel Ali in the United Arab Emirates, in which 7,000 companies employ around 145,000 workers and which accounts for around 40% of foreign direct investment in the UAE.

Jebel Ali may well provide an economic boost for the region, but it also has form for suppressing moves for improved workers’ rights and conditions, as documented by human rights groups and local journalists. The World Socialist Website refers to Jebel Ali as a place where a “young and largely immigrant workforce, mostly recruited from rural areas in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the Philippines, toil in overcrowded work camps”. That might give an indication as to how this port could be so profitable.

The European Union, which hosts several dozen freeports, has become increasingly cynical about the concept, but a large number of new such zones have sprung up in developing countries. This raises the question as to why the UK, an advanced Western democracy with a long history of workers’ rights, would want to copy them.

Given that there are already allegations of abuse and below-minimum wage work in the UK, it won’t wash to hide behind the argument that ‘it couldn’t happen here’. You only need to look at the Leicester garment industry, where the demand for cheap fast fashion is being met by sub-minimum wage employment – as exposed serially by the media; or at Sports Direct, where working conditions have been likened by MPs to a Victorian Workhouse, and the grim, badly paid, high pressure, low security work provided by titans of the gig economy. As it tries to reverse the gradual export of jobs to lower cost countries, some instances of the UK’s ‘onshoring’ of manufacture has simply led to the import of dreadful working conditions.

At the parliamentary debate, even supportive MPs were concerned that there should be provision against the rise of exploitative jobs.

Freeports come in several different guises and recently the ones that have made headlines are those in which goods are stored and traded without customs duties or sales tax – the ones that function more as giant warehouses storing oligarch art, luxury objects or museum grade artefacts.

Titillating readers on a regular basis is the entertaining but also depressing story of Yves Bouvier, who has been the subject of multiple investigations and scandals. Bouvier, also known as ‘The Freeport King’, owned and operated freeports in Geneva, Singapore and Luxembourg. He has been accused of harbouring looted antiquities and cheating Russian tycoon Dmitry Rybolovlev out of excessive sale commissions, and faces allegations of large-scale tax evasion. Bouvier, who strongly denies all the claims, has since had to relinquish ownership of his company.

The Bouvier scandals and other freeport-related misdeeds – including the hiding of Nazi-looted art and ISIS-looted antiquities from the Middle East, as well as the swindling of Picasso’s stepdaughter out of some of the painter’s works – have all featured in studies by those who want to crack down on regulatory gaps that allow freeports to facilitate money-laundering and tax evasion.

According to the inter-governmental Financial Action Task Force, the sharp recent increase in freeports has been linked not so much to a sudden rush for greater economy-boosting manufacturing but the growth of art as a big investment vehicle. Artworks that owners wish to store long term, possibly until a sale, are filling increasing amounts of floorspace across the globe, keeping works out of the public – and the taxman’s – eye for years. Freeports have become increasingly attractive in the wake of global government crackdowns on bank secrecy and tax evasion.

“Freeports provide a soil for misuse of competitive advantages and attract money laundering and tax avoidance activities,” wrote Barnard in another study, this time with Cambridge postdoctoral researcher Emilija Leinarte. “Since regulation in free zones is low, they may result in reduction in workers’ rights and standards. The largely unregulated global trading in art, which according to some estimates amounts to around $57 billion, is yet another area susceptible to fraud.”

“In addition to tariff reductions and other benefits,” the report went on, “freeports provide storage services and so are often at a centre of illegal dealings in art… Perhaps these are some of the reasons why the EU, the birthplace of freeports, is rather reluctant to develop free zones.”

German politician Wolf Klinz has led demands that Le Freeport Luxembourg – located near the duchy’s Findel airport – which was opened during outgoing EU president Jean-Claude Juncker’s tenure as prime minister – should close, and he believes that such facilities are generally undesirable because of the way they can be exploited.

“It is apparent to me that the risk of maintaining a facility of Le Freeport Luxembourg’s reputational profile within the EU customs territory could greatly outweigh the benefits,” Klinz wrote in a letter to Juncker.

There has been a swathe of reports in recent years from organisations such as the World Bank and the UN, all pointing the finger at the risks posed by freeports. There has been more regulation in the interim, but loopholes remain.

Curator, collector and art writer Kenny Schachter has, in the past, highlighted this issue. He has previously warned how the art world is being used for money laundering, because the wealthy realised “you can’t make a deposit or withdrawal at a bank without them looking at your underpants”, and has described untaxed sales made on private planes or in freeports.

He told The New European he had simply wanted to deliver a “wake up call”. As a prolific user of freeports for his classic cars and the portion of his art collection that no longer fits in his own display space at home, he said there was a legitimate purpose and need for the sites. As well as offering somewhere to store art until the owner decides whether to hang their painting in Manhattan or the Bahamas or sell it on, freeports also offer the kind of expert care it is difficult for an individual to manage at home.

Regulations have become much tougher, he adds, and this has had some effect on money laundering at freeports: “The extent of illegality in the art market is perhaps a bit exaggerated. If you want to evade tax there are a million ways to do it.”

Yet the beneficiaries of this type of freeport are clearly more likely to be the non-dom oligarch rather than the unemployed Teesside factory worker. When I ask Schachter about manufacturing and job opportunities in the kind of freeport he is most familiar with, he is startled. “That’s ludicrous. What on God’s earth would a freeport make? The only way they contribute to a piece of manufacturing is a storage box – and they’ll screw you for it on price. It’s just another sector for the real estate market really.” Of Johnson’s plans for boosting employment in parts of Britain, his verdict was succinct: “Nonsense.”

Whatever happens inside the freeports – whether they are for storing or making things or both – the concept seems more geared towards a kind of Singapore in Blighty rather than the advertised glorious utopia of gainfully employed workers. In the end, it all seems to speak to the same ideology – low tax, low regulation, low cost for the bosses, less obvious advantage for everyone else.

One thing Boris Johnson and his fellow Tories do not allude to too often is that the UK actually had its own freeports quite recently. Between 1983 and 1988 six free trade zones were established, but there was little apparent use for them once the single market was created in 1993. They were eventually closed by 2012, ironically the year that Britannia Unchained appeared, calling for their resurrection.

The obvious conclusion for this is that the new freeport creation now starts looking more like damage limitation from the fallout of an unnecessary and harmful Brexit rather than a great new hope for the economy. It could effectively be seen as creating tax haven-style conditions for a handful of places in order to make up for the privileges lost to the entire country because of leaving the EU.

In that case, would government efforts be better spent elsewhere? For all their prominent backers, are freeports, little more than a gimmick?

FREEPORT CHAMPION?

Jean-Claude Juncker, the outgoing president of the European Commission, has faced strong criticism for his response to claims that freeports enable money laundering.

Earlier this year, MEPs on a European parliament committee on financial crime and tax evasion described how the sites circumvented the normal international rules on transparency.

Among those they investigated was one in Luxembourg – called Le Freeport – which was authorised when Juncker was prime minister of the country.

MEPs who visited Le Freeport described it as “a black hole”.

“We came away from our visit to Le Freeport with a lot of apprehension,” Anamaria Gomes MEP told the BBC. “This is a way that could be easily used to store goods away from anybody’s control, for putting them in the dark when it’s more convenient, avoiding tax.

“The controls were extremely perfunctory and we did not see any real attempt to establish who were the real owners of the goods.”

In response to general criticism of freeports, the Commission praised their advantages of the sites, as “useful to simplify commercial operations”, adding there was “no evidence showing that free zones in the EU are systematically used to commit fraud”.

A spokesman for Juncker said he had “personally and tirelessly” pursued an agenda against money laundering and tax evasion.

The owner of Le Freeport said it made sure the tenants who rent its space conform to best practice in anti-money laundering controls.