On a nationwide speaking tour, GAVIN ESLER has encountered many examples of the UK’s recent history being reinvented.

The small town of Rye on the south coast is an English jewel. Just along the road from the site of the Battle of Hastings and the momentous events of 1066, the cobbled streets and old ale-houses of Rye tell a story going back centuries.

In a church hall at the top of the hill I was talking to an audience of about 150 people on ‘The Normalisation of Lies in Public Life’. But what was revealing was the way in which we sometimes lie, innocently, even to ourselves.

Obviously we all tell lies. We all know it is wrong, yet occasionally we lie so as not to cause offence.

“Yes,” we say, “I loved that shirt you gave me for my birthday”, even if it is consigned it to a bottom drawer. Or we gush, “yes, your new hairstyle suits you”, because we do not want to hurt a loved-one’s feelings. And is anyone truthful when buying something online and being forced to tick a box showing we have read the terms and conditions. Have you ever read the terms and conditions? Seriously? Me neither. But you have ticked the box, right?

At the Rye event, after my speech, there were many questions and then one man, I would guess in his 70s, took the microphone and angrily denounced the European Union as a dictatorship which had imposed unwelcome laws on him and the entire United Kingdom.

I asked him which two or three laws imposed by the EU on Britain had affected him personally the most. There was a silence. A long silence. Could he name even one law imposed by the EU that had personally affected him? He admitted he could not think of any. Not one. And yet he was strongly convinced that somehow his life had in been blighted by laws from Brussels in general, although in particular not one came to mind. This man was not alone.

I have been travelling around the UK speaking to diverse groups about the future of Europe and the future of Brexit as part of a tour promoting my book, Brexit Without the Bullshit. Most of these public meetings are fun. Some are truly inspiring, but a few – like the one in Rye – are sometimes a puzzle.

So was an event in Conway Hall. For those who do not know this wonderful London landmark, it is historically a venue of civilised debate on ethical issues. Again, my topic was lies and lying in public life.

This time I was asked a question by a woman who said she had voted for Brexit in the referendum of 2016. When someone says “I voted for Brexit” I respect their decision but always inquire as to which version of Brexit they voted for. This woman was absolutely clear.

“I voted for a ‘clean Brexit,'” she said confidently, explaining that it meant “leaving the European Union with no deal on October 31.”

Unfortunately almost every part of that sentence after the words ‘I voted’ is impossible. The phrase ‘clean Brexit’ entered the popular vocabulary only after a book of that title was published in August 2018, two years after the referendum.

Moreover, the words ‘clean Brexit’ have no clear meaning, rather like previous Brexit slogans of having ‘deals’ called ‘Canada plus’, ‘Norway plus’ or ‘managed no-deal’. Once you add in the word ‘plus’ or ‘managed’ or ‘clean’ to any ‘deal’ it can mean anything you want it to mean. ‘Jumping Off A Cliff plus’ could mean having a parachute. Or not. But this woman could not have voted as she claimed, for other reasons too.

As we all know, no-deal was never an option on the 2016 Brexit ballot paper. Prominent politicians wanting Brexit – Nigel Farage, Liam Fox, Michael Gove and Boris Johnson – explicitly ruled it out. They stated that Britain would leave the European Union with a deal, and generally (they claimed) a very good deal because, as they put it “we hold all the cards” for the “easiest trade deal in history”.

Finally – and most obviously – in June 2016 no date was fixed for leaving the EU, so the woman could not possibly have voted to leave on October 31, 2019. That date was only fixed in April 2019, after an earlier delay, from March 2019, which itself was only fixed as a leaving date when Article 50 was invoked in 2017 – not when this woman voted for Brexit in 2016.

How could it be that otherwise apparently sensible individuals manage to convince themselves of things which, objectively, simple are not true, and ‘facts’ which are simply not facts at all?

Napoleon Bonaparte once wryly observed that history “is a set of lies agreed upon”. There will come a time when Britain’s current struggles with leaving the EU will result in historical essays on Brexit and perhaps a learned book or two. But as these two incidents suggest, historians will find it difficult to agree on any set of ‘lies’ or ‘truths’ when they look back over current events in Britain.

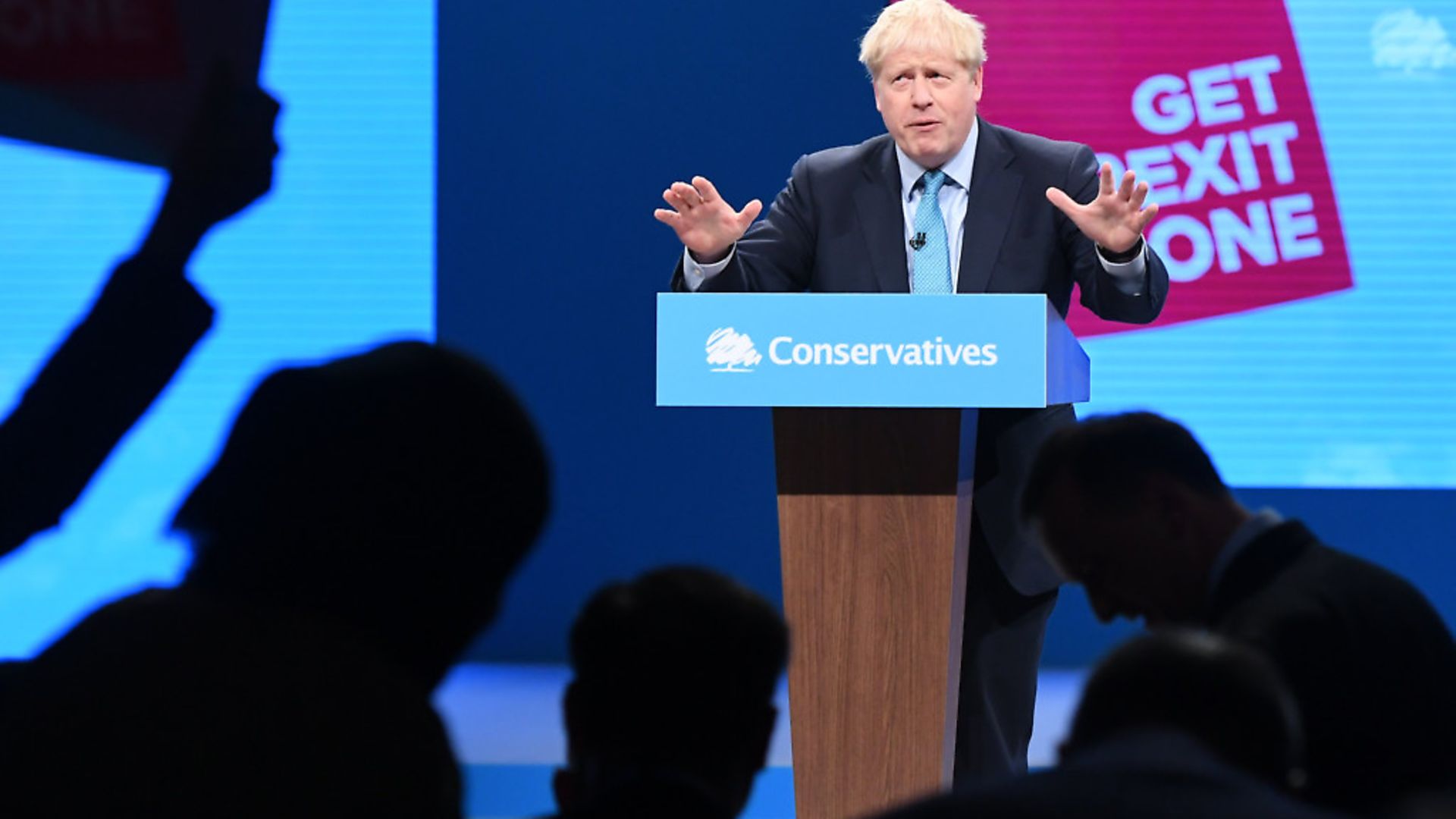

We cannot agree on ‘truth’ right now. This disagreement about truth and lies, facts and fiction, extends from those ordinary citizens in Rye and Conway Hall to politicians at the very top of the government. EU leaders and diplomats have made clear they do not believe Britain’s prime minister Boris Johnson has a plan for Brexit or is even actively seeking an agreement. Johnson himself says he is energetically working for a deal with all sorts of inventive plans – though what these may be, well, we do not know. Perhaps we will agree the Brexit ‘truth’ or ‘lies’ in the end, but this kind of dispute extends much further.

These examples are part of a phenomenon known grandly as ‘historical negationism’. It means humans give accounts of the past by selectively (and sometimes deliberately) ignoring or denying troublesome facts which undermine their case.

On the day I had the discussion in Conway Hall, British newspapers began running extracts of the autobiography of the prime minister who got us into the Brexit mess in the first place, David Cameron.

His ‘factual’ account of our recent history did not please either side in the Brexit debate. The Sun called it “Mills and Boon for Remainers”, referring to a particularly soppy kind of fantasy love story. The Guardian excoriated the former prime minister for a self-serving account, pretending that the referendum mess for which he was responsible was really “a ‘boon’ for Britain if the Leavers’ dastardly tactics hadn’t stopped him from getting his message across to the great British public”.

Cameron’s account side-steps the uncomfortable fact that until he forced a referendum upon us in 2016 membership of the EU was an issue of little concern to the vast majority of the British people. Whatever he claims in his account, the facts are that Cameron led a woeful campaign. And he lost. And so did our country.

The term ‘historical negationism’ was coined in 1987 by the French writer Henry Rousso to describe histories of the Nazi occupation of his country and the puppet Vichy regime.

Rousso argued that many of these accounts ignored what the French call collabos – French men and women who collaborated with the Nazis and helped enable the deportation of Jewish citizens to the death camps.

The British historian Sir Richard Evans was called to give evidence in another famous case of wartime ‘historical negationism’, that of David Irving. Irving was described as a “Holocaust denier” by the American historian, Deborah Lipstadt, and he sued her for libel. Thanks in part to Evans, Lipstadt won the case and Irving has been utterly discredited. Evena argued that “reputable and professional historians do not suppress parts of quotations from documents that go against their own case, but take them into account, and, if necessary, amend their own case, accordingly”.

‘Reputable and professional’ politicians should think about Evans’ words right now. It’s not only historians who sometimes fail to ‘take into account’ facts and documents which undermine their own views or prejudices.

Donald Trump publicly defended his factually incorrect claims that a hurricane was predicted to strike Alabama. When he was corrected by climate experts he refused to ‘amend his case accordingly’. He persisted in something which was clearly false.

Boris Johnson has been repeatedly confronted with past statements he has made and responded with his own ‘historical revisionism’.

He has simply denied he has made various controversial remarks, when television footage clearly shows that he is not telling the truth.

Neither Trump nor Johnson appear to suffer from any sense of shame when their lies are exposed. Nor do they appear to suffer any real sanctions for failing to tell the truth. Their failure of honesty is part of a virus infecting public life and it stretches right down to the woman in Conway Hall and the man in Rye who, no doubt, genuinely believe in good faith that what they are saying is true.

David Cameron joins a long line of leaders trying to justify himself to history by writing it himself. Julius Caesar did the same in his account of military campaigns against the tribes in what is now France in De bellis Gallicis. Winston Churchill wittily suggested that “history will be kind to me for I intend to write it”.

But even if Churchill and Caesar made some factual errors (as we all do) they at least attempted to offer the truth as they saw it. Nowadays ‘historical negationism’ and denying the truth from the past are only part of the problem. The real issue in 2019 is denying the truth in the present.

From the man at the public meeting in Rye to the woman in Conway Hall to the newspapers which propagate various kinds of fiction right up to the unelected serial liar who is currently prime minister of the United Kingdom, the virus of lying has infected our democracy. We need to find a cure for the normalisation of lying.