In the week Vladimir Putin backed moves to allow him to stay in office until 2036, broadcaster GAVIN ESLER reports on his new podcast investigating the backstory of the Russian president and the state he has created.

Winston Churchill famously captured the complex puzzle that was Russia, under Stalin. In 1939 the Soviet Union had entered into a pact with communism’s mortal enemy, Nazi Germany, to carve up Poland. Churchill understood Berlin’s motives all too well. But what was going on in Moscow? What were the Russians and their leader thinking? What would they do next? Churchill, in a radio broadcast, told listeners: ‘I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.’

The same is true of 21st century Russia under Vladimir Putin. The former Ukraine president Petro Poroshenko summed him up thus: ‘Putin wants the old Russian empire back.’ But is that really true? And if so, how is the country held together? What is the role of the oligarchs whose money has funnelled out of Russia to buy the trappings of wealth in cities like London and New York? And what is the relationship between Putin and those oligarchs?

These are pressing questions, particularly given the serious charges which have been levelled against the Kremlin regime and its associates: the mysterious deaths of various domestic critics, cyber attacks on its neighbours, the annexation of Crimea, military action in Ukraine, where its forces were implicated in the downing of the civilian airliner MH17, the bombing of civilians in Syria, various sporting doping scandals and, closer to home, the murder of Alexander Litvinenko, the attempted killings of Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury and attempts to subvert the democracies of the US, Britain and elsewhere. Such an extensive charge sheet begs another question: What will the regime do next?

It was in search of answers to such questions that we began the podcast The Big Steal. It’s a nine-part series in which – with the help of some of the best known Russia experts and Putin watchers – we piece together the extraordinary story of a Russian leader who himself is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma – a man whom some of those we have spoken to believe could be the world’s richest man and some characterise as its most successful criminal.

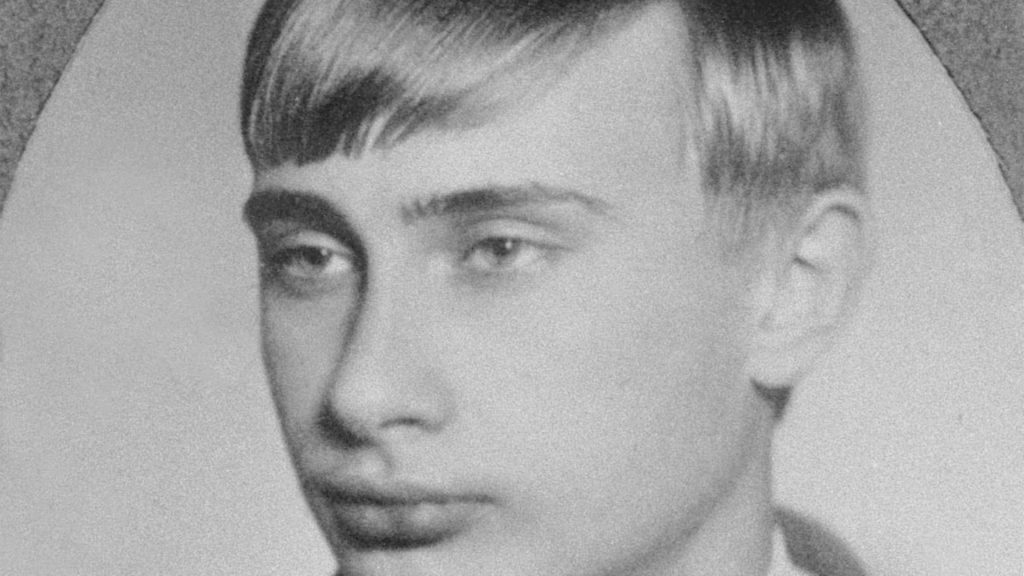

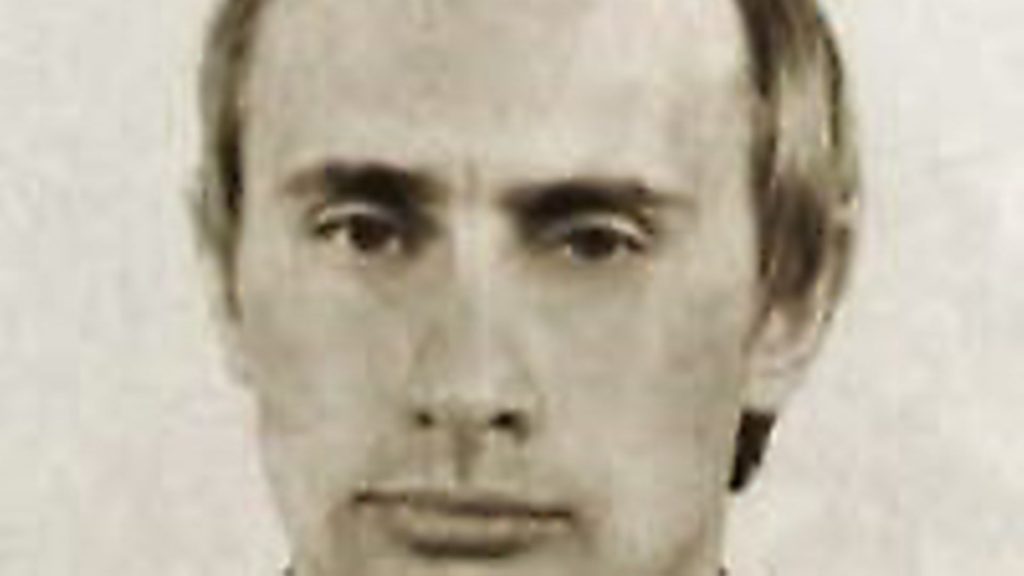

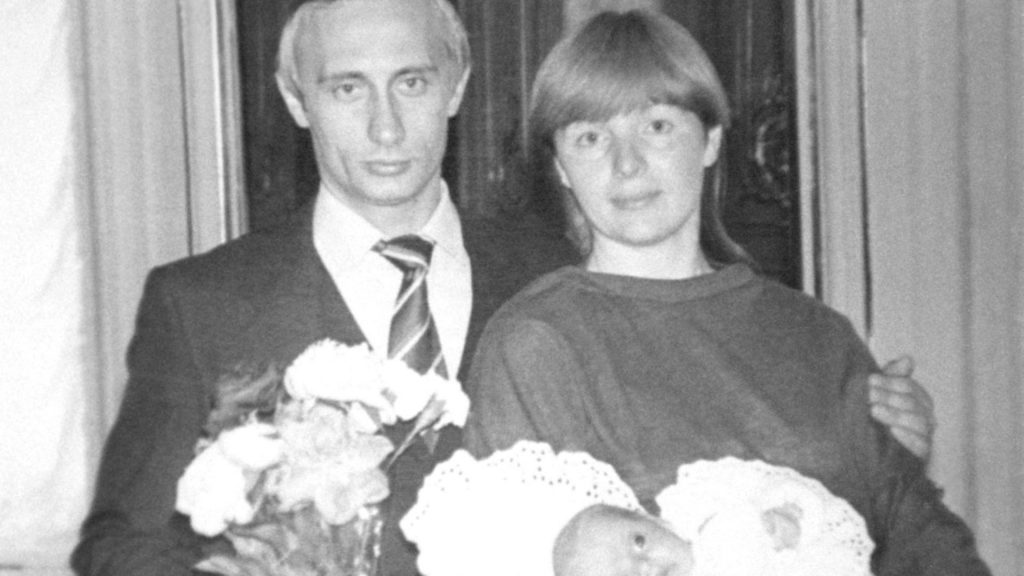

Born in Leningrad (now St Petersburg) in 1952, Putin was raised as an only child – his two brothers having died before his birth. He joined the KGB in 1975 but as a colonel in the late 1980s he had to make do with a very unglamorous posting to the East German city of Dresden.

He was there in 1989, as the Berlin Wall came down and hundreds of young Germans surrounded the Dresden offices of the KGB to demand that the Russians inside leave. One of the protestors present told us that a cool-headed KGB officer poked his head out the door and told the demonstrators the Russians were indeed leaving but that anyone who tried to enter KGB headquarters would be shot.

That cool-headed KGB officer was Vladimir Putin. Soon after, he returned to Leningrad where he became an astute and reliable political fixer for the men who had real power. He also began his own political ascent, initially in St Petersburg local government, then in the Boris Yeltsin’s administration – including a stint as director of the FSB, the KGB’s successor agency – and ultimately as prime minister and president.

Part of his aura of power has been his KGB past. In recent years, he has burnished his macho image: he has been photographed out hunting, exploring the Siberian wilderness, judo fighting, projecting himself as the epitome of Russian masculinity. So, I put it to Mark Galeotti, author of We Need To Talk About Putin, that the president seemed like Russia’s James Bond. Galeotti replied the image did not fit the facts.

‘He was a clerk [in the KGB], he wrote reports. I don’t know if anyone read them. Although he was in the first chief directorate, which is meant to be the elite foreign intelligence department, he never got beyond East Germany. There’s this idea of him being a Russian Bond. He was more of a Miss Moneypenny.’

Galeotti says Putin’s real skill – put to good use in Russia in the 1990s after the fall of the Soviet Union – was as a fixer ‘working with corrupt figures and having their back’.

Those skills have helped Putin gradually accrue not just immense political power, but also great financial power. Amazon’s creator Jeff Bezos is commonly described as the world’s richest man, with a fortune reputed to be over $116 billion. But many of those we have spoken to for The Big Steal suggest Putin – a man who rose from a very humble background and who has always been employed by the state – may actually be richer.

Anders Aslund, a Swedish economist and well-connected Russia-watcher with the US think-tank the Atlantic Council, told me that he considered Putin a ‘trillion dollar criminal’, although he says his money is shared by many others in his circle. On our podcast, we heard Putin described as the head of a ‘clique of bandits’.

There have been many accounts suggesting how Putin came to achieve this position. For the series we focused on two cases in particular. The first is that of Yukos, a Russian oil company. It is a tale which tells the story of Russia over the past 30 years.

In communist times, Yukos had control of some of Russia’s most valuable assets: the oil and gas that lies underground. When the Soviet Union collapsed, Russia became like the Wild West, with mafia gangs killing rivals, entrepreneurs and buccaneers trying to buy state assets being sold on the cheap and a political system struggling to reform itself and keep order.

One of the young buccaneers in those lawless times was Mikhail Khodorkovsky. He began running a small cafe – a tiny capitalist affair of the type which in the Stalinist period might have led him to the Gulags. As things improved he set up a small bank, Menatep, and then when the financially bankrupt Russian state started to sell off major assets, he bought Yukos and set about transforming the company along western lines.

Khodorkovsky brought in western advisers and western-style accounting, and began forging links with American oil companies. In the process, he became Russia’s richest man.

But then, as Khodorkovsky told me, he over-reached himself. Concerned that corruption was not just something unfortunate that was happening in Russia, but becoming something eating away at the country, he seized the opportunity to try to do something about it. In February 2003, he confronted president Putin about the subject in a televised meeting, implying that government officials were accepting huge bribes.

Naively, you might say, or at least very optimistically, Khodorkovsky thought Putin might crack down on some of the corruption. In the TV confrontation Putin remained as calm as he had been when facing down the mob in Dresden. But then, just a few months later, Khodorkovsky was arrested and charged with fraud and tax evasion, the very crimes which he had alleged were at the heart of corruption in the Russian state.

What followed was a show trial, with Russia’s richest man, Khodorkovsky, placed in a cage in a courtroom and ultimately sentenced to prison.

One of those watching the court case with great interest and growing alarm was an American investor in Russia, Bill Browder, who provided our second account of power and corruption. Like Khodorkovsky, Browder had been fighting off various corrupt officials.

For the podcast, I asked Browder why Khodorkovsky had been put in a cage on television. He laughed, grimly. He asked me to imagine being one of the 20 richest men in Russia, knowing that Khodorkovsky was the richest and the smartest of all. ‘You’re in your yacht at Cannes,’ Browder said. ‘You turn on CNN and see Khodorkovsky in a cage.’ So what do you do? ‘You go to Vladimir Putin and say, ‘Vladimir, what do I have to do not to end up in a cage?”

And what’s Putin’s answer, I wondered.

‘Fifty per cent,’ Browder said. You have to hand over 50% of the money you make.’

Now, of course, Browder was not present at any of those discussions, but he characterises colourfully how he and others believe modern Russia is run.

Countless times, during our research and recordings, we were told that Putin leaves businesses alone, provided that the oligarchs – the richest business owners – stay out of politics. And, say these critics of the regime, the president and his friends are rewarded financially as a result, which is why in the West, Russian officials on what appear to be modest middle class salaries are able to afford apartments and houses which cost millions in London and New York.

As Browder put it, ‘Vladimir Putin is a crook. He’s like Pablo Escobar but with nukes. He’s the richest man in the world. He’s killing people in different countries, he’s killing people in his own country and getting away with it.’

Of course with Browder, it is personal. In a long and complicated series of confrontations with the Russian authorities Browder too was accused on trumped up charges of tax evasion. An Interpol ‘red notice’ was issued by the Russian authorities demanding his arrest. A Russian colleague working for him, Sergei Magnitsky, was arrested, horribly mistreated and died in Russian custody.

Browder as a result has become a strong campaigner for what is called (in Sergei’s memory) the Magnitsky Act, passed by the US Congress and replicated elsewhere. It is aimed at making sure the many people involved in Magnitsky’s death are not rewarded by being able to bring out their money from Russia to spend in the West.

Browder now lives in London, as does Khodorkovsky, who was pardoned by Putin and released from prison in 2013, saying he would stay out of politics.

From the many people we talked to in the making of the series – Khordorkovsky, Browder, Alexander Litvinenko’s widow Marina, cyber warfare and intelligence specialists, lawyers, politicians, investigators – there was another question which kept being raised: Russia’s malign influence in the world is not a secret, so why is so little being done about it?

Have your say

Send your letters for publication to The New European by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk and pick up an edition each Thursday for more comment and analysis. Find your nearest stockist here or subscribe to a print or digital edition for just £13. You can also join our readers' Facebook group to keep the discussion and debate going with thousands of fellow pro-Europeans.

Well, a fightback of sorts has begun. In February a court in the Hague awarded the former shareholders in Yukos $50 billion – yes, $50bn – compensation from the Russian state for seizing their assets.

They may never see the money, but they at least have the endorsement of their case from a European court. The Big Steal was funded thanks to their assistance because they wanted their story told, among others we uncovered. The editorial content is the work of the producers and me – and we want the story told because it is important.

Western states, too, are waking up to the threat, politically and militarily. As Boris Johnson put it, while serving as foreign secretary: ‘It is clear that Russia is now a malign and disruptive force.’

An Estonian air force colonel working on cyber defence told me about a cyber-attack from Russia on his country: ‘At Nato HQ when they told allies, the first response was ‘well, where are the tanks and where are the aircraft?’ Nato, he said, is now more atuned to the idea of ‘hybrid warfare’ – cyber attacks and information warfare designed to throw western countries off balance.

But governments need to do more. After all, Putin is not going away any time soon. This week he backed constitutional amendments that would allow him to seek another term in office, in 2024, and, potentially, again in 2030. As another defence and intelligence expert put it to me: ‘Just because we are not at war with Russia does not mean Russia is not at war with us.’

So what does Russia want? What lies behind all the riddles and enigmas? The journalist, historian and Russia expert Anne Applebaum put it most clearly: ‘Russia is a revisionist power. It wants to change the rules. It doesn’t like the liberal world order, it doesn’t like the EU, it doesn’t like Nato. What it wants – and this is not a secret – they’ll say this – is to roll all of that back.’

And perhaps there is one clue which really does solve the modern Russia enigma. Why is Vladimir Putin so successful, bestriding the world stage despite the great weaknesses of the Russian economy? The answer, as I heard numerous times, is the sport at which he excels. He is a judo fighter. The central characteristic of a skilled judoka is to use his opponent’s strength against him. As a former intelligence agent put it to us, ‘search for your own weaknesses, and that’s where you find the KGB’. Right now, we have plenty of weaknesses. Maybe we need to search a little harder.

The Big Steal podcasts are now available on Audible, Spotify and elsewhere