A new study finds that while young women are more left-wing than men of the same age, older women are more right-wing. ROSALIND SHORROCKS, who carried out the research, explains what it means

That younger people are often more likely to vote for left-wing parties than their older peers is well established, and has inspired the old adage that people become more conservative with age. But new research I have carried out suggests that the trend is particularly pronounced among women.

The study, using data from more than 40,000 people in several Western European countries, as well as Canada, found that younger women are the most left-wing in their voting habits – but that older women are the most right-wing.

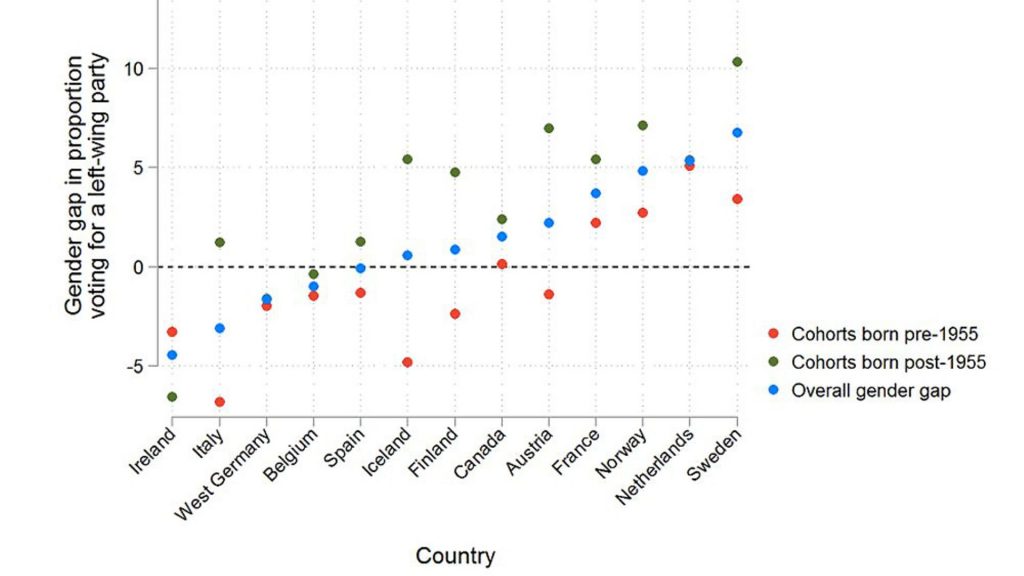

This trend is summarised in the graph below. Negative numbers indicate more men voting for a left-wing party in a given country. Positive numbers indicate more women voting for a left-wing party. In almost all countries, women born after 1955 are more likely to vote for left-wing parties than men of the same age group.

Conversely, in many countries, women born before 1955 are less likely to vote for left-wing parties than their male peers.

The research also showed that the gender gap in left-wing voting became larger for each new birth cohort. So, for example, the difference between women and men in left-wing voting was even greater for those born 1975-85 than it was for those born 1965-75. This suggests that over time we should expect women to become more and more left-wing relative to men, as younger, more left-wing cohorts of women replace older, more right-wing cohorts in the population.

The analysis shows that the decline of religiosity is crucial to explaining the trend. Older women are more religious and this is a more important factor in their vote choice compared to younger women.

On the other hand, younger women tend to have a stronger preference for redistribution and see a larger role for the state compared to men. They vote for left-wing parties in line with these preferences.

Parties often make particular efforts to appeal to ‘women voters’ when campaigning. However, this analysis shows that there are considerable differences between younger and older women in their voting preferences. Appealing to the ‘women’s vote’ might make less sense than, say, appealing to young women or older women.

This is a challenge for both left and right-wing parties. Conservative and Christian democratic parties have historically had strong support among religious women, who are concentrated in older generations. However, this is now a cause for concern. Although older voters are more likely to turn out to vote than younger voters, the religious older generations are also becoming a smaller proportion of European electorates through generational replacement.

Older generations die out and are replaced with new, secular ones.

Left-wing parties, especially social democratic ones, need to think about whether their younger women supporters will stick with them as they age. If they do, this perhaps offers hope for these parties. As their traditional support base of the working class declines in size, they might find a new one in the form of younger cohorts of women.

However, in the intervening period, these left-wing parties will face a challenge of balancing the different values and priorities of their traditional base – older, working class men – and their new supporters – younger cohorts of women. Both left-wing and right-wing parties may have to start reexamining how they appeal to female voters.

The research used data from 40,000 people as part of the World Values Survey/European Values Study, from 1989-2014. It did not include voters from the UK.

Rosalind Shorrocks is a lecturer in politics at the University of Manchester; this article also appears at www.theconversation.com