Next in the series looking at great European lives, Charlie Connelly looks at the life of Bert Trautmann.

There were 17 minutes left of the 1956 FA Cup final when Birmingham City outside-left Alex Govan punted a high ball towards the edge of the Manchester City penalty area. Centre forward Eddy Brown headed the ball towards the edge of the six-yard-box where teammate Peter Murphy hared in to meet it as goalkeeper Bert Trautmann raced from his line.

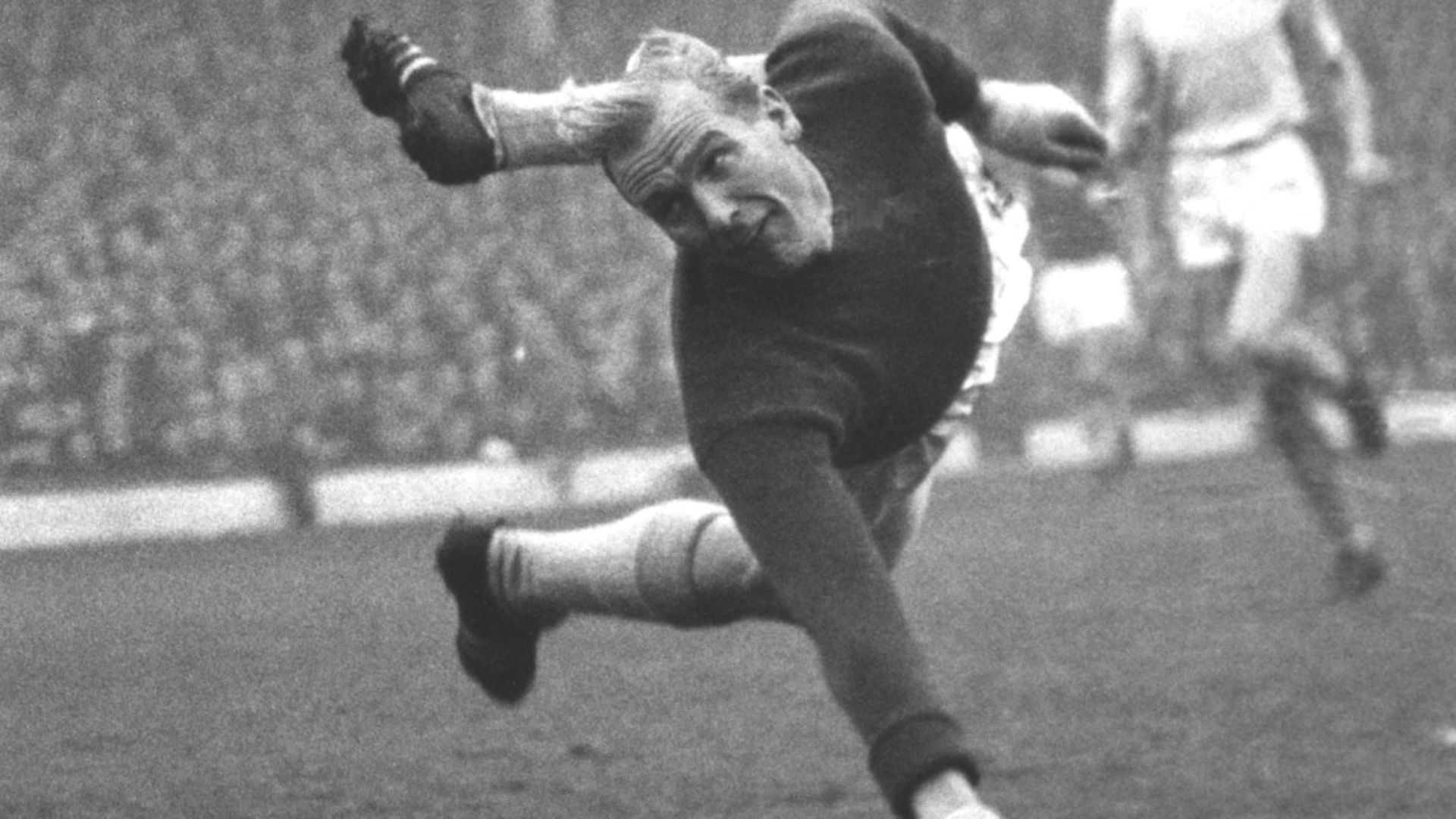

Plunging forwards, the 6ft 2in German grabbed the ball a fraction of a second before Murphy arrived.

The Birmingham forward’s studs caught in the turf and his knee braced just as Trautmann’s momentum carried him into an unavoidable collision.

The goalkeeper turned his head at the last second but Murphy’s knee crunched into his neck in a clash that left both players prone on the turf.

Murphy was soon up again, wincing and flexing his knee, but Trautmann stayed down for several minutes, receiving lengthy treatment from the Manchester City trainer.

When he was hauled to his feet the goalkeeper was still clearly dazed, holding his hand to his neck as he twisted his head in all directions, blond hair flopping this way and that.

While his team led 3-1, these were the days before substitutes and if Trautmann had to leave the field his side would be down to ten men with an outfield player forced to take his place in goal. Still wincing, he assured the concerned physio he was fine to play on.

As the final minutes ticked down, a groggy Trautmann barely knew where he was, yet despite the pain he managed another brave dive at the feet of Murphy before the final whistle sounded to give Manchester City the trophy.

Four days later, still sore and suffering a persistent headache, the goalkeeper called into the Manchester Royal Infirmary where an x-ray revealed that he’d dislocated five vertebrae while the second vertebra had split into two pieces. In short, Bert Trautmann had broken his neck.

The doctors were aghast. The smashed second vertebra had lodged against the third, preventing further damage and effectively saving his life, but something as simple as the team bus from Wembley driving over a pothole could have killed him, they informed an ashen-faced Trautmann.

It remains one of the great tales of football bravery, but even without playing the final minutes of an FA Cup final with a broken neck Bert Trautmann’s story would have been extraordinary enough.

A dozen years before that sunny afternoon at Wembley the man to whom the crowd had sung For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow when he’d struggled to his feet was a paratrooper in the Wehrmacht, barely out of his teens and fighting to halt the Allied advance into Normandy after

many traumatic months on the Russian front.

The young Bernhard Trautmann, ten years old when Hitler came to power in 1933, was an enthusiastic member of the Hitler Youth in his native Bremen, joined the Luftwaffe as a radio operator as soon as he was old enough and was eventually transferred to the elite Fallschirmjäger parachute regiment.

‘Growing up in Hitler’s Germany you had no mind of your own,’ he said later. ‘You didn’t think of the enemy as people at first. Then when you began taking prisoners you heard them cry for their parents. When you met the enemy he became a real person. The longer the war went on, the more you started having doubts.’

As the German forces fell apart during the war’s final days Trautmann decided to set off on foot for home.

It wasn’t long before he was captured by a British unit who, according to Trautmann, greeted him cheerily with, ‘Hallo Fritz, cup of tea?’

Transported across the Channel with other prisoners Trautmann was taken first to a camp outside Northwich, then to Ashton-in-Makerfield near Wigan from where he was put to work clearing debris from the Blitz and defusing unexploded bombs.

‘My education only began the day I arrived in England,’ he recalled. ‘People were so kind and decent. They didn’t see an enemy prisoner, they saw a human being.’

The prisoners would pass their free time playing football, with Trautmann proving a handy centre-half. One afternoon he hurt his leg and took over in goal, playing so well and enjoying it so much he made it his permanent position.

In 1948 he signed for local side St Helens Town where not only did he marry the chairman’s daughter, he made such rapid progress it wasn’t long before scouts from some of England’s leading sides were flocking to the club’s Hoghton Road ground. Burnley seemed favourites to sign Trautmann but in the end it was Manchester City who secured his services in October 1949.

Memories of war were still fresh and the prospect of a former Wehrmacht paratrooper, a holder of the Iron Cross no less, playing in goal for City caused a sensation.

Letters of protest poured in to the club and to local newspapers, ex-servicemen returned their season tickets and Manchester’s Jewish population expressed its horror until the city’s Chief Rabbi spoke up for Trautmann.

‘Despite the terrible cruelties we suffered at the hands of the Germans we would not try to punish an individual German, who is unconnected with these crimes, out of hatred,’ said Alexander Altmann after Trautmann had suffered relentless abuse in his first match at Bolton Wanderers. ‘If this footballer is a decent fellow I would say there is no harm in it. Each case must be judged on its own merits.’

In addition the German faced the huge task of replacing legendary keeper Frank Swift who had just retired after 16 years at Maine Road.

Yet despite heavy odds, Trautmann won over the City fans and the country at large by being an excellent goalkeeper.

Indeed, when he took the field at Wembley that day in 1956 he’d just been announced as Footballer of the Year, the first foreign player ever to receive the award.

Despite his popularity Trautmann still knew dark times.

He had witnessed terrible things during the war, especially on the Russian front, and had once been buried alive for three days when the Allies bombed a school in which his unit was billeted.

Barely two weeks after he broke his neck the Trautmanns’ five-year old son John was run over and killed outside a local sweet shop.

Encased for months from head to hips in plaster, Trautmann had plenty of time to dwell on painful memories.

Sometimes his demons would emerge on the field: in 1962 he was sent off against West Ham United for leathering the ball against the referee’s back after disputing a goal he’d suspected was offside, while in his last ever competitive game, for non-league Wellington Town in 1964 shortly after leaving City, the 41-year old was given his marching orders for foul and abusive language.

Most seriously of all, in 1971 he drove wordlessly away from the family home in Anglesey two days after Christmas and disappeared for a month, sparking a search involving Interpol before he turned up in Manchester.

After his retirement from playing Trautmann coached around the world, managing teams in Tanzania, Liberia, Pakistan, Malta and his native

Germany, not to mention guiding the Burmese national side at the Munich Olympics.

His heart and home remained in England, however, and for all his celebrity there Trautmann remained virtually unknown in Germany. He never returned there to live and the national team refused to consider him for selection as he was based overseas.

He is immortalised in football lore as the goalkeeper who broke his neck, but as the only high-profile German in post-war British popular culture his role as an important figure of conciliation between two warring nations is usually overlooked.

During his time in the camp, like many POWs he would visit local families and became close to one St Helens woman in particular, who had lost a son during the war.

She was asked if she resented the presence of a former Wehrmacht soldier in her home.

‘Of course not,’ she replied. ‘He’s just some mother’s son.’