The practically inseparable couple who met their ends on the fateful voyage of the Titanic.

There are few more mythologised events in history than the loss of the Titanic. It shouldn’t really be possible to romanticise the avoidable deaths of more than 1,500 people in the cold north Atlantic on the clear, starry night of April 15, 1912, but as major disasters go the sinking of the unsinkable ship on its maiden voyage has produced a plethora of anecdotes of varying plausibility, from the orchestra going down playing Nearer, My God, To Thee to the fact that even if all the lifeboats had been launched at full capacity, 1,000 people would still have ended up in the water.

With blame for the disaster being been pinned on a range of culprits from a mislaid pair of watchman’s binoculars to capitalism, our fascination with the most infamous disaster of the 20th century grows ever stronger as the cloud of myth grows ever thicker.

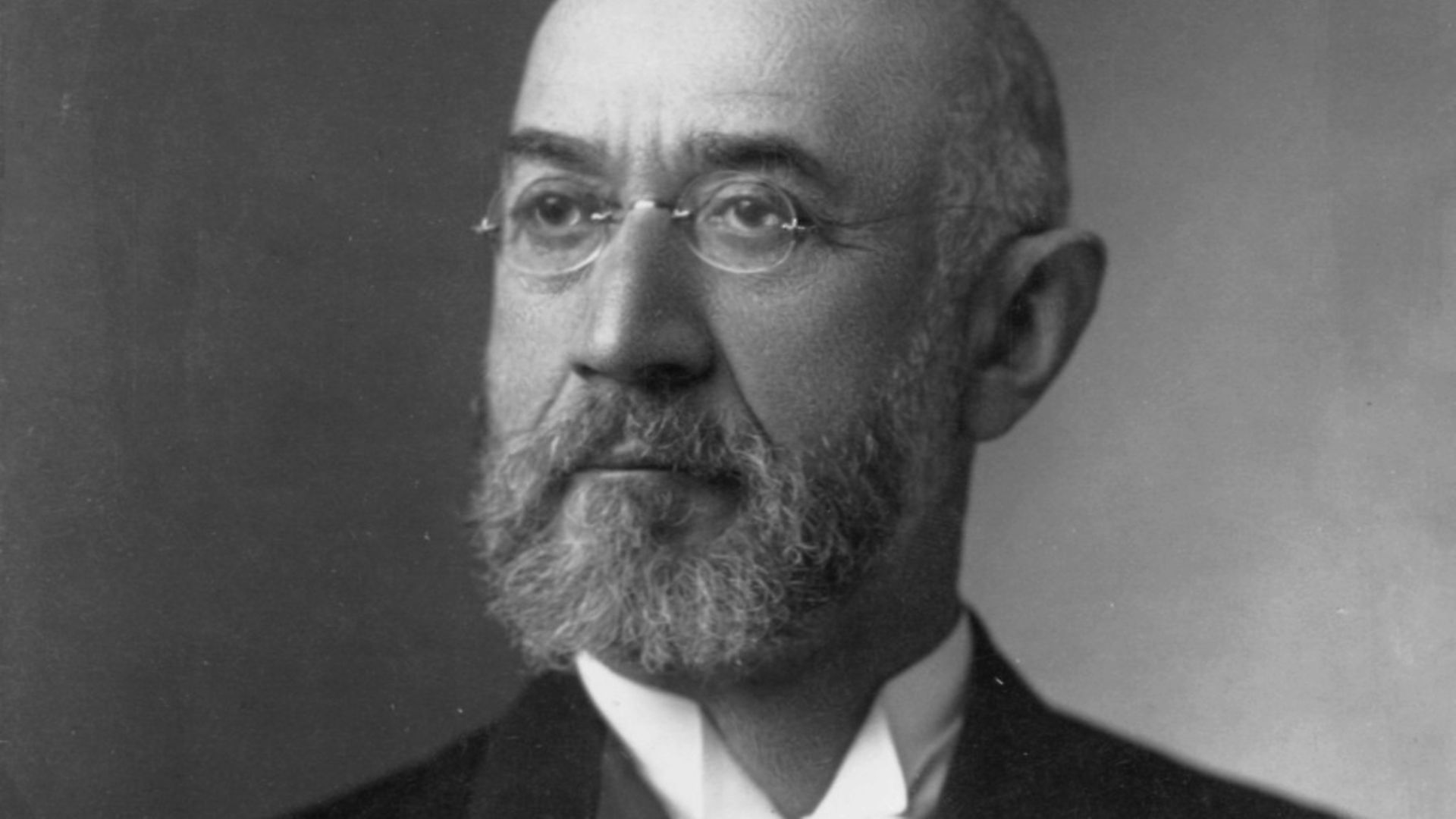

One story that appears to stand up, however, is the account of the dignified ends of Isidor and Ida Straus. Isidor was the 70-year-old co-owner of Macy’s, then the largest department store in the United States, who was heading home to Manhattan after avoiding the bone-chilling New York winter through a few weeks in the south of France and his native Bavaria. Ida was his wife of 43 years.

The couple were well-known in New York society for their vast wealth and philanthropy but also for being practically inseparable, with Mrs Straus accompanying Isidor on most of his business trips. On the very rare occasions they were apart the pair would write long letters to each other every day.

The Strauses usually crossed the Atlantic by German liners, usually the Amerika, but the fanfare surrounding the Titanic proved irresistible and the couple booked passage on the new pride of the White Star Line. They joined the ship at Southampton from where it left for New York on April 10. During the voyage they mixed easily with the other first class passengers, who included some of the world’s richest men in John Jacob Astor, John Borland Thayer and Benjamin Guggenheim.

On the night of April 14/15, once the iceberg had torn a gash along the starboard side of the liner and condemned her to the bottom of the ocean, the Strauses found themselves among passengers gathered next to Lifeboat 8 with Isidor’s valet John Farthing and Ida’s maid Ellen Bird. Madeleine Astor, already in the boat, saw Ida and gestured that she should join her, indicating an empty seat beside her.

Ida looked at her husband who indicated that she should go ahead, at which Ida made it clear that she had no intention of leaving the ship without him. One of the sailors, keen to see the boat launched as soon as possible, told Isidor there was room for him too.

‘As long as there is a woman on this vessel I will not leave,’ he said.

‘You are an old man, Mr Straus,’ said the crewman.

‘I am not too old to sacrifice myself for a woman,’ he replied.

Ida, noticing that Ellen Bird was shivering in the lifeboat, removed her fur coat and handed it to her on the grounds that, ‘I won’t be needing it anymore’. As Bird accepted the coat, a couple of sailors attempted to manoeuvre the 66-year-old Ida into the vessel as she leaned towards it. A brief struggle ensued after which Ida broke free of their grasp and declared, ‘I will not be parted from my husband’. Isidor pleaded with her to join the other women in the boat but Ida was determined.

‘We have been together for many years,’ she said. ‘Where you go, I go.’

Some survivors’ accounts have it that as the lifeboat was rowed away from the stricken vessel the couple were seen arm-in-arm on the deck, others that they retired to two deck chairs to await the inevitable.

Fellow first-class passenger Archibald Gracie, whose account of the disaster is one of the most eloquent and reliable, wrote later that he saw the Strauses washed away as the ship’s stern rose into the air prior to slipping beneath the waves, helping the couple’s calm acceptance of their fate to become one of the most striking images from all the accounts that emerged from survivors arriving at New York.

Isidor’s body was recovered a few days later by the Mackay-Bennett, a British-registered cable-laying ship contracted by the White Star Line to search for the dead around the site of the sinking, but Ida was never found. A month after the disaster a crowd variously estimated at between 20,000 and 40,000 gathered at and around Carnegie Hall in Manhattan for a memorial service dedicated to the couple. Andrew Carnegie himself spoke, giving an emotional tribute to the Strauses while the city’s mayor William Jay Gaynor gave a heartfelt eulogy.

‘He thought little of himself,’ the mayor said of Isidor. ‘In fact he always seemed to me in the manner of talking as unconscious of his own physical existence.’

Ida’s sacrifice was lost a little in the noise surrounding the deaths of so many eminent men (the Associated Press even put out a story two days after the disaster lamenting how tycoons and magnates had gone down with the ship while their respective places in the lifeboats were taken by ‘some sabot-shod, shawl-enshrouded, illiterate and penniless woman of Europe’), and when she was mentioned it was frequently in loaded terms.

‘In this day of frequent and scandalous divorces,’ said the American Israelite, ‘when the marriage tie once held so sacred to all is too lightly regarded, the wifely devotion and love of Mrs Straus for her partner of a lifetime stand out in noble contrast’.

Rosalie Ida Blun was born in Worms in the south of Germany four years to the day after her future husband and barely 35 miles from his home town of Otterberg. She arrived in the USA in 1851 with her mother and siblings following her father Nathan, a clothing merchant who had emigrated a year earlier to escape the financial uncertainty that followed the 1848 revolutions in Europe.

Ida met Isidor Straus, a business associate of her uncle, in New York in 1866 when she was 17 and he 21. Friendship turned into romance and the couple were married on July 12, 1871. They would go on to have seven children, one of whom died in infancy.

Like Ida, Isidor had also arrived in the US with his mother and siblings to join his father. Lazarus Straus had left Otterberg in 1852 and opened a general store in Talbotton, Georgia, where the rest of his family arrived two years later.

Having worked for his father in the shop, Isidor in his late teens became a successful blockade runner for the Confederacy and spent time in Europe selling Confederate war bonds. He returned to the US at the end of the war and with his brother Nathan relocated to New York to establish a branch of the earthenware, china and porcelain business that Lazarus’ simple store had expanded into.

In 1874 the brothers secured the contract to run the china and glassware department at Macy’s and opened factories in France, Switzerland and Germany to help meet the huge demand for their products. So successful were the Strauses that in 1896 the brothers were able to buy out the owners and take over the entire department store, an acquisition that made them multi-millionaires.

Isidor and Ida became well known for their philanthropy, often in support for New York’s Jewish institutions. No less an authority on philanthropy than Andrew Carnegie said at the memorial service, ‘whenever a good cause languished their sympathies were aroused and both with head and heart they gave not only much-needed money but what was more important and much more rare was that they gave themselves to the work’.

The more reliable estimates suggest there were 2,227 people on board the Titanic that night, of whom 1,522 lost their lives. There are many stories of chivalry and heroism among passengers from first class to steerage, but the actions and words of Ida and Isidor Straus, whose lives had mirrored each other’s from birth and whose devotion kept them together to the end in the Atlantic Ocean that had defined their lives, comprise one of the most enduringly poignant stories of the disaster.