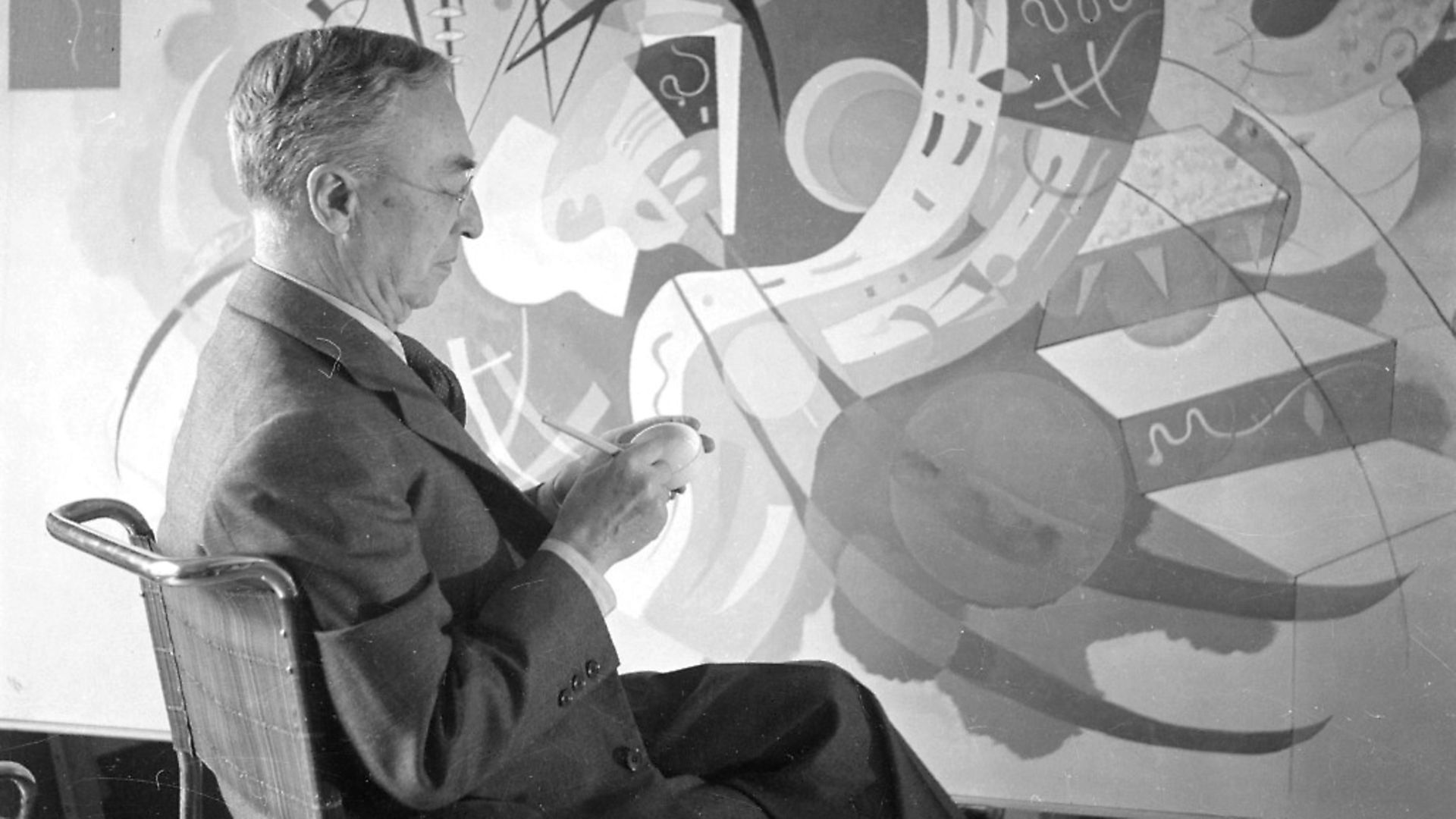

CHARLIE CONNELLY reflects on the work of iconic Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky.

On January 2, 1911, in Munich, 45-year-old Wassily Kandinsky attended a concert of music by the avant-garde composer Arnold Schoenberg. While the Austrian hadn’t yet completely abandoned traditional tonality his Second String Quartet and Three Pieces For Piano, Opus 11, both of which Kandinsky heard for the first time that night, were huge, discordant advances in the dismantling of the prevailing techniques and philosophy of music.

‘Dissonances are only different from consonance in degree; they are nothing more than remoter consonances,’ Schoenberg was quoted as saying on the concert poster that convinced Kandinsky to buy a ticket. ‘Today we have already reached the point where we no longer make the distinction between consonances and dissonances.’

The music he heard that night set Kandinsky firmly along the path to the abstract art in which he was a key pioneer, confirming he wasn’t alone in seeking a precision through texture and form in the artistic expression of profound emotion.

His long-term aim was a visual language beyond artistic convention in which the role of colours, shapes and lines went way beyond the reproduction of people, objects and landscapes to a pure form of expression evoking strong and deep emotions.

As he sat in the audience listening to Schoenberg’s blurring of the lines between consonance and dissonance, Kandinsky experienced something close to an epiphany and within two days he had spilled onto canvas his response to the third piano piece with his Impression III (Concert). In the painting the grand piano is just about recognisable, a featureless black slab that appears almost to be leaping upwards out of the frame.

It is surrounded by a tide of yellow that washes out of the instrument, over and around the rough-hewn figures representing an audience which seems almost to be drawn physically towards the pianist and the instrument. It is an exhilarating representation of the joy and power of live music and the interaction between performer and listener and exactly what Kandinsky strove to achieve through his work: visual prompts that invoked emotions towards a higher spiritual truth.

A fortnight later the artist finally plucked up the courage to write to Schoenberg. ‘What we are striving for and our whole manner of thought and feeling have so much in common that I feel completely justified in expressing my empathy,’ he gushed.

‘I understand you completely,’ replied the composer, ‘and I am sure that our work has much in common, especially in what you call the ‘anti-logical’ and I call the ‘elimination of the conscious will in art’.’ Impressions III (Concert), a major step towards that goal, could almost be an artistic representation of synaesthesia, a condition whereby two or more senses find themselves reacting to an external stimulus conventionally aimed at one, for example, an ability to smell sounds. For Kandinsky, music produced colours and patterns, something he’d first experienced as a youth in Moscow at a performance of Wagner’s Lohengrin. ‘I saw all my colours in spirit, before my eyes,’ he recalled. ‘Wild, almost crazy, lines were sketched in front of me.’

It worked the other way too – from around 1910 Kandinsky named all his paintings in musical terms under the headings Impressions, Improvisations and Compositions – and while he always denied that he was creating pieces of music on canvas, something he described as ‘impossible and unattainable’, Kandinsky had from childhood believed that each colour at least had a spirit and personality of its own.

Born in Moscow to a wealthy tea dealer father and a mother descended from the Mongolian aristocracy, Kandinsky spent most of his childhood in Odessa, although the family would travel widely through central Europe and Italy. This widening of horizons had a profound effect on his art and when he moved to Moscow to study law and economics, the city’s architecture and Russian Orthodox iconography proved to be key early influences.

Although he was a keen artist, as a young man Kandinsky felt the serious practice of art to be a ‘luxury unavailable to a Russian’ and instead concentrated on law and economics. He always felt the pull of art, however, and a trip during the 1890s to see some works by Rembrandt on a student visit to the Hermitage at St Petersburg, combined with a period spent in Vologda, close to Siberia in the rural north of the country, studying local judicial processes that introduced him to folk art only fuelled this increasing interest. Yet it took until he was 30 for Kandinsky to begin painting in earnest, having experienced a revelation in front of one of Monet’s Haystack series at an 1896 exhibition in Moscow.

‘It took the catalogue to inform me it was a haystack,’ he wrote later, ‘because I could not recognise it as such. This non-recognition was a painful feeling for me. I considered that the painter had no right to paint indistinctly, feeling that the object of the painting was missing. Yet I noticed with increasing surprise and confusion that the picture not only gripped me, but impressed itself irrevocably on my mind. Painting at that moment took on a fairy-tale power and splendour.’

Kandinsky had been mulling over the offer of a professorship at a university in Estonia but instead he packed his bags and decamped to Munich to study art under Anton Abzé. The legacy of that Monet moment is clear in his early works, which are strongly impressionistic. But when in 1909 he moved to Murnau in the Bavarian hills, the landscapes he produced there show a clear progression towards abstraction with their strong brushstrokes, simple shapes and loud colours.

When Germany declared war on Russia in 1914 Kandinsky found himself suddenly an enemy alien in the land he called home and he was forced to return to Moscow, where he witnessed and embraced the Russian Revolution. Within a year of the Bolsheviks coming to power Kandinsky was professor at the Moscow Academy of Fine Arts and a member of the arts section of the People’s Commissariat for Public Instruction, effectively a culture ministry.

So mutual was the respect between artist and revolution that his memoir Retrospect was published by the state publishing house. In 1919 he was a founder of the Institute for Artistic Culture, became director of the Moscow Museum for Pictorial Culture and helped to organise a string of museums across the country. A move to the prestigious Moscow University followed, as well as the foundation of the Academy of Artistic Sciences, but when the Soviet regime began to cool in its attitude to the avant-garde in favour of socialist realism, Kandinsky realised that if he was to have a future involving free artistic expression it would lie outside the Soviet Union.

A move back to Germany followed and a senior post at the Bauhaus school, at the invitation of founder Walter Gropius, only for politics to intervene once again when the Nazis closed down Bauhaus almost as soon as they came to power in 1933. Settling in the Paris suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine, Kandinsky saw nearly 60 of his works removed from German galleries and museums, 14 of them included in the notorious Degenerate Art exhibition in Berlin in 1937.

Kandinsky lived through extraordinary times, the great 20th century shifts in European history and politics arriving repeatedly on his doorstep. As a result his art illuminates the turbulence of the period, providing both an abstract commentary on and escape from the events of the day.

‘Lend your ears to music, open your eyes to painting, and – stop thinking!’ he advised. ‘Just ask yourself whether the work has enabled you to walk about into a hitherto unknown world. If the answer is yes, what more do you want?’