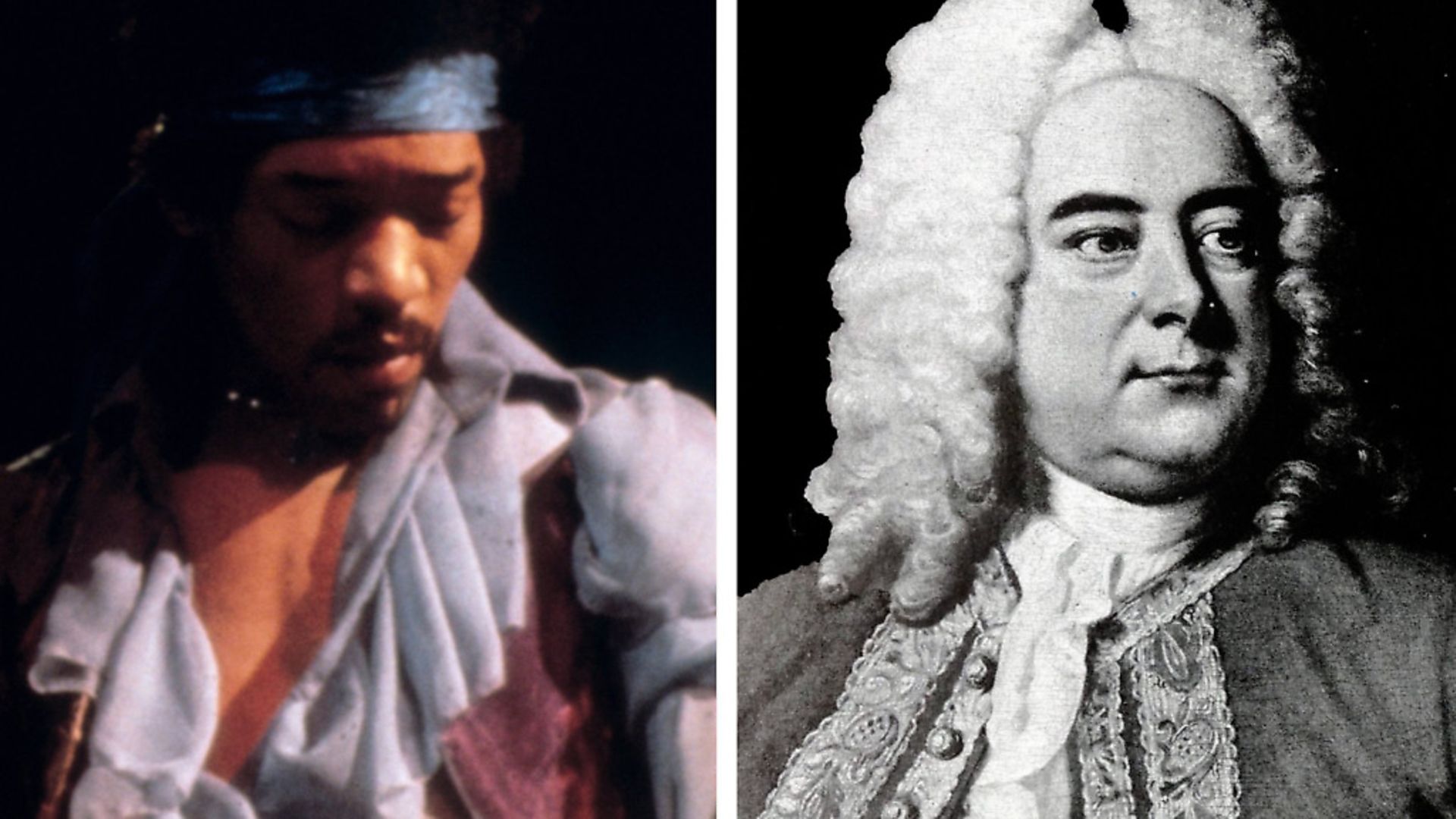

Two centuries apart, Handel and Jimi Hendrix set up home in the same London property from which they proceeded to redefine music.

George Frideric Handel and Jimi Hendrix shared two things: musical genius and a London address. The Handel House Museum at 23-25 Brook Street, Mayfair – the home of the German master of the baroque for 36 years – rebranded as Handel and Hendrix in London last year, its third floor offices having been ‘restored’ to their bohemian shabbiness of the late 60s when Hendrix lived there. The attraction is now sold as ‘the only Hendrix home in the world’.

The London experience of these two men, 200 years apart, was very different, but both saw their careers reach maturity in the city. While both are heavily identified with their birth countries – the Seattle-born Hendrix was a superstar on a scale only the US could produce, his performance of The Star-Spangled Banner at Woodstock symbolising the new American identity of the Vietnam generation, and Handel was the propagator of continental styles of opera practiced in Hamburg – they became honorary Londoners.

It was a cosmopolitan London that a 25-year-old Handel first visited in late 1710. A beneficiary of the patronage of the trans-European aristocracy, he had recently become Kapellmeister to Prince George, the Elector of Hanover. He performed for Queen Anne at St James’ Palace in early 1711, quickly following this by premiering his opera Rinaldo at the Queen’s Theatre.

When he decided to settle in London in 1712 he joined a significant population of European migrants, not least some 20-25,000 Huguenots who had sought refuge in England following the 1685 Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, which outlawed the practice of Protestantism in France. The accession to the throne of his patron Prince George in 1714, becoming King George I, sealed Handel’s British connections. He moved into the newly-built property at Brook Street in the rapidly-developing and genteel area of Mayfair in 1723 and would become a naturalised Englishman four years later.

By the end of Handel’s life, London was the biggest city in Europe, an economic and cultural powerhouse with a diverse population and districts with their own distinctive character – this was the London whose heady social mix Hogarth captured in his engravings. The composer’s haunts included Walsh’s Music Shop, the publisher and propagator of his works, just off the Strand, and White’s Chocolate House, a hot chocolate shop, gambling den, gentleman’s club and theatre ticket agency all in one, a short stroll away from Brook Street.

These were typical of the commercial venues that defined the public life of Georgian London and Handel flitted between the cultural hub of central London, where his works were performed on Haymarket and at Covent Garden, and his home in the fashionable West End. While the Händel-Haus in Halle has the claim of being Handel’s birthplace, Brook Street was where his most acclaimed works were conceived and brought to life and where this jovial yet difficult character held court.

In his prime, Handel was the very figure of the bon vivant, a life-long bachelor who pursued his personal passion for fine art, food and music with abandon. While Beethoven called him ‘the greatest composer that ever lived’, Berlioz’s description was the rather less complimentary: ‘a great barrel of pork and beer.’

His first biographer, John Mainwaring, writing in 1760, had reason to defend him at some length for being ‘a person always habituated… to an uncommon portion of food and nourishment’, saying that ‘nature had given him so vigorous a constitution… so craving an appetite, and that fortune enabled him to obey their calls’.

He was as generous with others as himself, however, and became an important patron of the Foundling Hospital in north London, staging annual benefit performances of his Messiah there. Hogarth was a founding governor and lured this art-lover with the Hospital’s rich collection of artworks, but he also found it a useful arena for putting on performances away from the bitter feuds and competition of London’s theatre land.

A pious man who was nevertheless a fluent swearer in four languages, uncompromising and driven but also generous and benevolent, a success who repeatedly teetered on the brink of bankruptcy, Handel was a contradiction, and Mainwaring said of him: ‘The greatest talents are often accompanied with the greatest weaknesses.’ The same might have been said of his fellow resident of Brook Street, two centuries later.

Jimi Hendrix was a jobbing musician when he signed a management contract with Chas Chandler, late of the Animals, and went to London in 1966. Chandler set about putting a band together for him – what would become the Jimi Hendrix Experience – and Hendrix cut his teeth as a frontman on London’s club scene.

The band’s first break came via a megastar of European pop. Johnny Hallyday, known as the ‘French Elvis’, was a teen idol who was coming under the influence of Dylan and fast becoming a plastic hippy when he saw Hendrix play in London. He booked the Experience as a support act and they played their first gig at the opening date of Hallyday’s short tour of France in October 1966. Hallyday would release his own French-language version of Hey Joe in 1967, the year after the release of Hendrix’s original which had peaked at number six on the UK charts.

The success of Hendrix’s debut single was quickly followed by a legendary gig at Soho’s Bag O’ Nails club on January 11, 1967. A who’s who of guitar greats was in attendance – Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page and Pete Townsend – along with Jagger, Lennon and McCartney, the Small Faces, and more ephemeral figures of 60s pop like Lulu and Donovan. The man who famously turned down a job fronting Led Zeppelin, Terry Reid, later recalled bumping into the Stones’ Brian Jones on the way back from the gents, and Jones proclaiming: ‘It’s all wet down in the front from all the guitar players crying.’ During this early visit to London Hendrix influenced the leading figures of British rock music at a pivotal time and nothing would be the same again.

It was two years after first coming to the UK, just as his fame was consolidating, that Hendrix set up home with girlfriend Kathy Etchingham at Brook Street, in an adjacent flat to that once occupied by Handel, moving in in July 1968. In an interview with the Daily Mirror in early 1969 Hendrix called Etchingham ‘My Yoko Ono from Chester’, and although he was often absent – either on tour or in other women’s beds – he would say that their shared flat was ‘my first real home of my own’, a significant statement given his rootless childhood. The freedom of the London of Carnaby Street and the permissive society was a revelation to Hendrix, who had toured in the segregation-era southern US and suffered from being pigeon-holed as a ‘black artist’ at home. The London scene was far less bothered by such categorisations, although Hendrix’s exoticism still drew attention on the streets as he and Etchingham explored all the West End had to offer.

Brook Street had the cream of London retail on its doorstep; Hendrix went clothes shopping at Fenwick, a couple of doors down on the other side of New Bond Street, and Selfridges. One Stop Records on South Moulton Street and the flagship HMV store just a block over on Oxford Street supplied copies of Handel’s Messiah (Hendrix took a sufficient interest in his predecessor’s work to perform a version of the Hallelujah Chorus live on at least one occasion). He and Etchingham furnished the flat in ‘souk chic’ with Persian rugs and wall hangings from Portobello Road and Chelsea antiques market, but they ordered the flat’s turquoise velvet curtains from the rather more formal drapery department at John Lewis. Hendrix’s army experience manifested itself in his daily making of the bed, which dominated the small flat, with military precision.

His time in London would exert some prosaic influences on him – he got into Coronation Street and pub culture (when Hey Joe went top 10 it was celebrated with a pint down the pub) – but it was also a pivotal time in his career. Famous visitors at the flat included Eric Burdon of The Animals, Ginger Baker and George Harrison, and during his residency at Brook Street he appeared on Dusty Springfield and Lulu’s hugely popular TV vehicles, sold out the Albert Hall and released All Along the Watchtower and the Electric Ladyland album. His final public performance would be at Ronnie Scott’s after his relationship with Etchingham had ended and he had moved back to the US. But these were crucial years in his short career and London afforded him opportunities the US had not.

Handel’s life in London was a tale of great success and of a long life well-lived. Hendrix was found dead at 27 in a Notting Hill flat, four years almost to the day after he first came to the UK. But even as they knew very different cities, for both these migrants London offered a welcoming face and a space to create and perform music which defined the eras in which they lived.

Dr Sophia L Deboick is a freelance writer and historian specialising in popular culture