CHARLIE CONNELLY takes a look into the life of German heavyweight boxing champion Max Schmeling.

Yankee Stadium, New York, June 22, 1938. It’s barely 90 seconds into the world heavyweight title bout between reigning champion Joe Louis and German challenger Max Schmeling and the American is already dishing out one of the most brutal pastings in the history of the sport.

Another left to the jaw has Schmeling staggering slightly and holding on to the top rope with his right hand to keep his balance. As Louis thuds another hard left into his solar plexus Schmeling pulls himself into the ropes and looks at Louis wide-eyed, as if he can’t quite believe what’s happening.

As Louis rounds on him and moves to swing a right, Schmeling instinctively turns his shoulder into the ropes. The punch thumps into his lower back and the German cries out, his oiled forelock flicking back as his whole body flinches. He didn’t know it at the time but that blow has cracked two of his vertebrae. Louis closes in, a right to the head, a left to the head, Schmeling’s knees buckle and for a moment his chin rests on the top rope.

The referee steps between them and Louis backs away, bouncing on the balls of his feet. Schmeling, half crouching, moves gingerly away from the ropes, his right hand finally releasing its hold as Louis closes in again. The stricken challenger brings his right arm around but instead of aiming a punch he extends it towards his opponent, palm outwards, as if pleading for mercy.

A quick one-two to the head from Louis and the German rolls onto the canvas, boots swinging through the air, but is somehow up on a count of four. Then he’s down again in a flurry of fists and finds the will to get up only for another burst to send him sprawling onto his hands and knees. This time the referee stops the fight a shade over two minutes after it had begun, 124 seconds that came to define the entire 99-year span of Max Schmeling’s life.

That visceral night in the Bronx was not just any world title fight, this was a match loaded with political tension and cultural significance. Louis, the 22-year-old Alabama-born, Detroit-raised champion, was a beacon for black America.

Schmeling meanwhile, nine years his opponent’s senior, represented something quite different: the Nazi fetish for Aryan superiority. In the tumultuous atmosphere of the late 1930s it was a bout over which nobody could be neutral (in its obituary of Schmeling the New York Times described it as ‘the undercard for the Second World War’) When he entered the ring that night Schmeling was greeted with a barrage of banana skins, drinks cartons and spittle.

Yet there was much more to Schmeling than an automaton representative of the political regime of his homeland. Indeed, of that pounding he took from Louis he said in 1975, ‘Looking back I’m almost happy I lost that fight. Imagine if I had gone back to Germany with a victory. I had nothing to do with the Nazis but they would have pinned a medal on me. After the war I might even have been considered a war criminal’. A post-war British tribunal would clear him of any suspicion of collaboration but the whispers would follow him for the rest of his life.

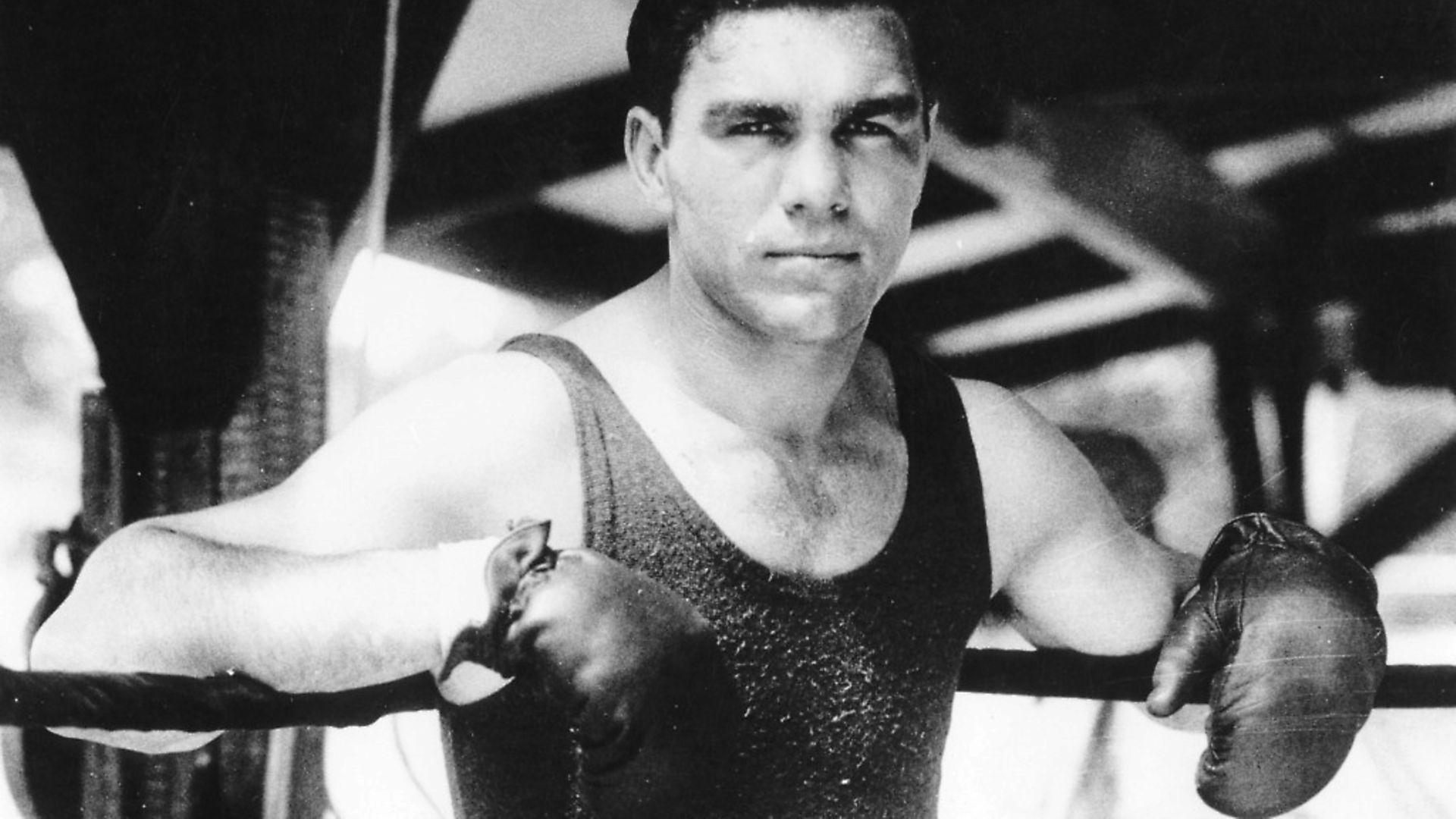

Schmeling was the ideal poster boy for the Nazi regime. Tough, good looking, successful and with a blonde, blue-eyed film star wife in Anny Ondra he was a public relations dream for the far-right. He was photographed with Hitler and Goebbels and his international prominence was celebrated by the Reich as evidence of German racial superiority.

Yet Schmeling was far from a willing Nazi stooge. He refused every entreaty to join the party, retained a Jewish trainer in the outspoken American Joe Jacobs, despite pressure from high up in the Reich ministry, and on Kristallnacht, the night of 9-10 November, 1938 when Jews and their businesses were attacked in a co-ordinated pogrom right across Germany, he sheltered two Jewish children in his suite at the Excelsior Hotel in Berlin, an act that could have had grave consequences.

‘If we had been found in his apartment I would not be here this evening and neither would Max,’ said one of the boys, Henri Lewin, at a dinner given in honour of Schmeling in 1989.

The fighter was in a difficult position. When he turned professional in 1924 the financial crash and hyper-inflation that brought a ruthless end to Weimar prosperity was still a long way off. Within four years he had become the German light-heavyweight champion and then claimed the European title: with the nation emerging from the trauma of war this was enough to make Schmeling a huge celebrity. ‘It was a time that demanded new heroes,’ he remembered, ‘being a fighter was symbolic.’

When in 1930 he fought Jack Sharkey for the world heavyweight title and won after Sharkey was penalised for a hit below the belt in the fourth round, it was just the tonic Germany needed in the face of a grievous financial crisis crippling the country.

By the time he’d lost the title to Sharkey in a controversial points decision two years later Nazism was on the rise and Schmeling was, however distasteful he might find it, its inevitable ambassador. That night in June 1938 would be the ultimate expression of what he represented, however inadvertently.

He and Louis had met before. Two years earlier the American was an undefeated world title hopeful on a wave of momentum that had him widely tipped for greatness while Schmeling was trying to earn himself another crack at the belt.

He’d studied Louis in newsreel footage and spotted a gap in his defence: the champion would drop his left hand after throwing a jab. In the ring at Yankee Stadium, where most pundits hadn’t given him a hope, it was that chink in the armour the German exploited methodically and mercilessly. Louis was on the canvas in the fourth and made it as far as the 12th round before Schmeling’s metronomic right-handers finally saw the fight stopped.

The American had to be carried from the ring and when he regained his senses in the dressing room said he couldn’t remember anything after the second round.

A congratulatory cable from Goebbels soon arrived. ‘Your victory is Germany’s victory,’ it said and a film of the fight played to packed houses in cinemas across Germany for weeks.

Schmeling was flown back across the Atlantic on the Hindenburg airship, landed escorted by the Luftwaffe, and was immediately required to watch a rerun of the fight with Hitler himself, who slapped his thigh with delight every time Schmeling landed a blow on Louis.

Two years later, after that sensational defeat by a pumped-up Louis still smarting from their previous bout (‘I don’t want nobody to call me champ until I’ve beaten Schmeling,’ he’d said) the German fighter’s return to Germany was quite different. Having spent a fortnight in hospital he made a low-key journey home, arriving in Berlin on a stretcher.

Having lost favour with the regime he became the only high-profile sportsman to be called up into the Wehrmacht, joining a parachute regiment where in 1941 he was reported to have been wounded during the battle for Crete.

Schmeling said later that was propaganda – he’d been suffering from a stomach complaint. Discharged from the army he would visit Allied prisoner of war camps where he would give out signed photographs and was widely regarded by those who met him there as genuinely opposed to Nazism.

He made a brief comeback after the war but retired from the ring in 1948 to run Hamburg’s new Coca-Cola franchise, a venture that made him very rich indeed. And while he was always loath to discuss that 1938 Bronx battering and its highly-charged context, he and Louis remained friends until the American’s death in 1981 (according to some reports he even paid for Louis’ funeral).

He might have lived for just shy of a century but in the eyes of history Max Schmeling will always be confined to those two minutes and four seconds of the rawest, most brutal mix of sport and politics ever staged.