CLAUDIA PRITCHARD on the new exhibition showcasing the influence of two Roman artists who pioneered the exuberance and ebullience of the ornate style.

The goddess Medusa had a look so poisonous it turned men to stone. But she met her match, not once but twice. First, the seafaring hero Perseus defied her deadly gaze by deflecting it in his shield, slaying her with the help of his makeshift mirror. Then the Italian sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) took his own revenge.

Making the punishment fit the crime, where Medusa – with serpents for hair – had turned her victims to stone with one look, Bernini rendered the severed head in marble. He popped her on a pedestal, reducing the monster to a salon curiosity.

But this conjuror in stone went further, retaining something repulsive in the now powerless face, making the snakes in their own death throes send one final shiver down the spine of the viewer.

Fear, revulsion and horror are among the emotions and reactions that are skilfully aroused by the prime artists of Baroque Rome, in the first ever exhibition to bring together Bernini and the painter who lived a generation before him: Michelangelo de Merisi da Caravaggio.

The two artists who defied both dimensions and conventions seem made to share a room, both on the strength of their similarities and their differences.

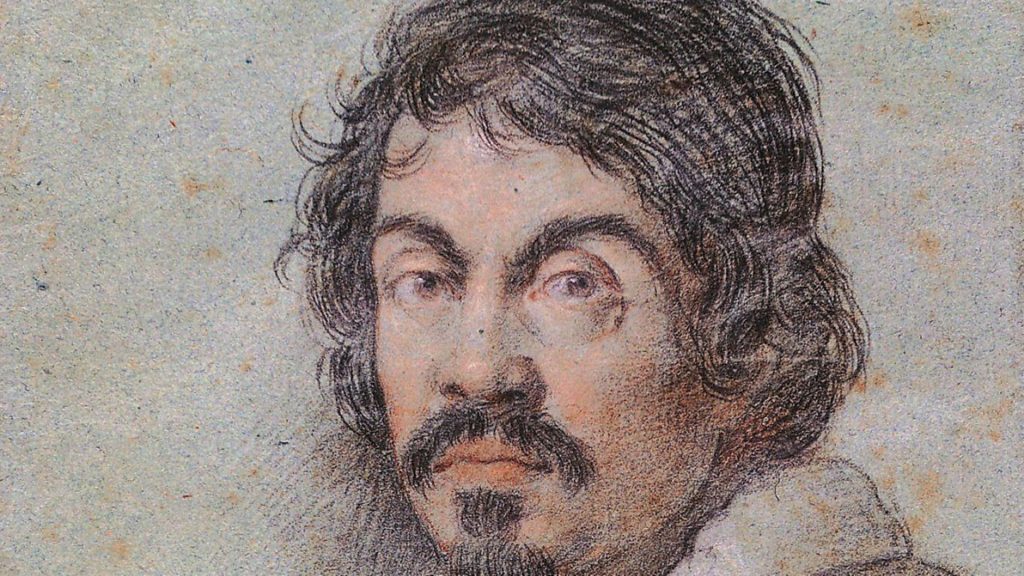

Caravaggio, born in Milan in 1571, followed the money to Rome in 1592, at a boom time for artists.

Wealthy patrons were enriching their growing collections with commissioned work, insuring their souls with commissions for innumerable churches and decorating ever more flamboyant palaces and apartments.

Bernini, who learnt at the knee of his sculptor father Pietro, was born into this lucrative scene, heir to a revolution in composition fomented by Caravaggio, whose own short life was as full of incident as his scenes.

Dead at 38 after years on the run, following a fatal fight, Caravaggio left a body of work so radically composed and intensely lit that his successors could do little more than copy his style before establishing their own.

Bernini grew up in a world of these Caravaggisti, whose figures broke free of the melodramatic poses of the 16th century Mannerists.

Caravaggio’s characters, and those of his followers, expressed the feelings, often not particularly heroic or virtuous, that viewers experienced themselves – alarm, resentment, suspicion or simply a sense of being overwhelmed.

They demonstrated too the failings that the same viewers observed in others: Greed, vanity, dishonesty.

Roma – Credit: Archant

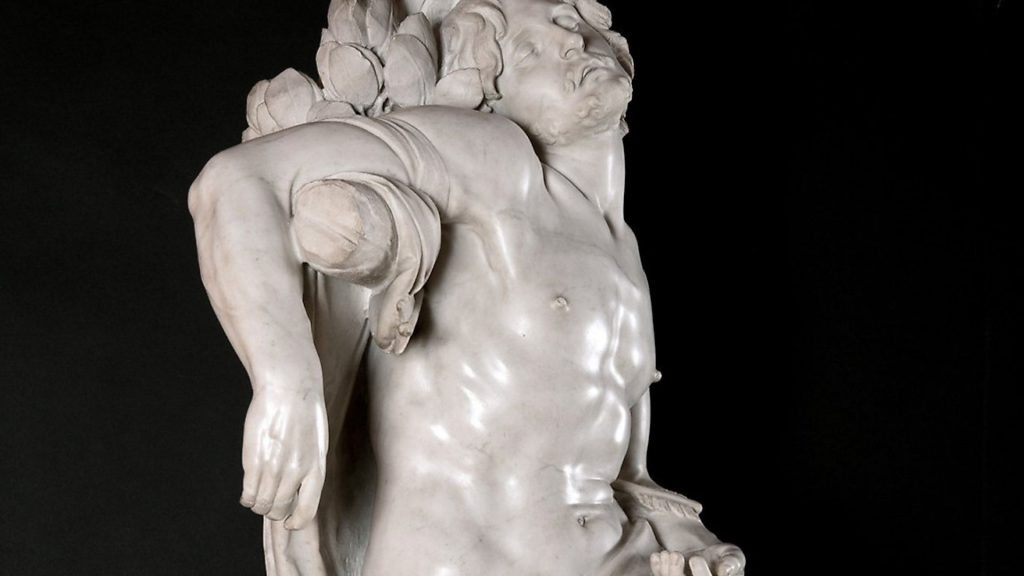

Caravaggio had brought sculptural physicality into his paintings; now it fell to Bernini to achieve with a chisel what painters suggested with colour and brushstrokes: A creeping blush, a pinch of flesh, a foam of lace.

Caravaggio & Bernini: The Discovery of Emotions, at the Kunsthistorisches museum in Vienna, celebrates with unashamed passion these two masters, displaying their work at that of some of their many contemporaries and artistic heirs, such as Andrea Sacchi and both Orazio Gentileschi and his daughter Artemisia.

Rather than studiously picking over chronology or technique, it encourages viewers to enter into an emotional force field, that has surprising resonances.

When David slays Goliath, a favourite subject in baroque art, he takes no pleasure in his conquest. World leaders who today revel in the fall of enemies can learn from his solemnity.

There are everyday shocks and anxieties too. When Caravaggio’s Boy Bitten by a Lizard (1597-98) falls back with surprise but also leans in to see what has happened, he is every person who has chosen a horror film, simultaneously terrified and thrilled.

Nearby, in the exhibition, Andrea Sacchi’s Daedalus frets understandably over his son Icarus, as he ties up the wings that will bear him; the know-all teenager shrugs off his attention.

Meanwhile, Orazio Gentileschi’s own version of a distraught father, Jacob, is torn between love and duty. His sacrificial boy, Isaac, is swapped only by angelic intervention for a handy ram.

Classical and religious stories may be the starting point of important works, but it is often the heartwarming detail that lingers, like the dirty feet of worshippers kneeling at the foot of Caravaggio’s masterpiece Madonna of the Rosary (1601-3).

Drapery is often so vigorously depicted on canvas or in stone it seems to have a life of its own.

But when Giuliano Finelli carved the bust of Cardinal Scipione Borghese in 1632 he gave his master Bernini a run for his money, revelling in the priest’s wrongly buttoned mozzetta and unruly tassels. The Cardinal may have been above such worldly considerations. Or, as the most ambitious collector in Rome (a calling helped by uncle Pope Paul V), he was planning his next acquisition.

Scipione’s palace in Rome, the Villa Borghese was, and is still, stuffed with treasures, including several of Bernini’s most virtuosic pieces.

As the exhibition’s co-curator Stefan Weppelmann observes in the book that accompanies the show, if Scipione spotted a gap in his collection, he helped himself to someone else’s, notably a Raphael in Perugia.

The pursuit of unattainable art is a special kind of lust, and for those with this insatiable desire the Baroque artists with their chiaroscuro effects and radical compositions were hard to resist.

Who knows for sure what Caravaggio was up to with his saucy little John the Baptist? With his cheeky come-on look and lithe prepubescent figure he hardly turns the viewer’s thoughts to higher things. There is no suggestion here that the adult John will end up with his head on Salome’s plate, but simply a jubilant celebration of the human form – an attractive torso and sinewy back, a frank display of genitalia and a pair of legs so long that if the boy walked off the canvas he would tower over us before toppling to the ground. But the artists working in the shadow of, and inside, the Vatican summoned up religious ardour aplenty too.

Caravaggio’s harrowing The Crowning With Thorns (1603) is a masterly study of persecution and resignation.

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Mary Magdalena in Ecstasy (seen for the first time outside a private collection, and on loan next year to the National Gallery’s Artemesia show) blurs the line, like Bernini’s terracotta Saint Teresa, between religious and sexual rapture.

Outside Rome itself, with its many immovable Baroque treasures, Vienna with its exceptional holding of Caravaggio in particular is a fitting host for this art of unashamed excess. And it unexpectedly brings together the past and the present. A modern world driven by emotional rather than cerebral responses resembles the headstrong 17th century.

Take comfort from an unexpected source: Caravaggio’s earnest David with the Head of Goliath demonstrates what happens when an overwhelming bully is taken on against all the odds. It didn’t end well for him.

Caravaggio & Bernini, is at Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, until January 19 and at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, from February 14 to June 7

Caravaggio and Bernini: Early Baroque in Rome is published by Prestel, £45