Leading pollster PETER KELLNER offers his analysis of why so many centre-left parties are floundering, and where their best hopes now lie

Are the glory days over for social democracy? Do voters now take for granted the great progressive reforms of the post-war era – pensions, education, healthcare, social insurance etc – and see no need to continue supporting the parties that first championed them?

Two weeks ago in these pages I explored the long-term roots of Labour’s decline here in Britain. I argued that it had suffered from massive economic and social changes over many years. This analysis goes wider, for similar economic forces have been at work throughout the industrialised world.

The picture looks bleak for progressives, not everywhere, but in enough countries to cause real concern. Elections since 2015 have produced the worst results in modern times for centre left parties in France, Germany, Holland, Greece, Austria, Sweden and Australia.

However, to make sense of what happened, we need a more systematic analysis than cherry-picking, or perhaps rotten-cherry-picking, the most dramatic national stories.

I have collected data which shows what has happened to 15 centre-left parties that have all, at one time or another, governed their countries. Thirteen, such as the Labour Party, are members of the Socialist International. I have added in America’s Democrats and Canada’s Liberals; neither has ever been socialist, but both are the long-standing progressive rivals to the parties of the right.

Let’s start with this simple contrast. In the post-1945 era, the centre-left regularly won more than 40% of the vote in 13 of the 15 countries. In the latest national elections in each country, only three parties won more than a third of the vote. Another three parties have slumped to single-digit percentages.

So: many progressive parties face strong headwinds. Recent success stories are the exception, not the rule. Warnings come from various countries of voters switching en masse to other parties: the Greens in Germany, social liberals and smaller left wing parties in the Netherlands, the far left and En Marche in France, Syriza in Greece – and, indeed, the SNP in Scotland, as well as the Tories in ‘red wall’ England.

Even in Spain and Sweden, where the centre left is still in power, its voter base has been eroded by Podemos (Spain) and the Left party among others (Sweden). The need for the centre left to renew itself for the post-industrial age is both clear and urgent.

One thread that runs through this story is the significance of electoral systems. In eight of the 15 countries in the chart, support for the centre left at the most recent election was at least 20 points below the post-1945 peak. Seven of those countries have proportional voting systems. In contrast, of the seven countries where the fall from peak-to-latest share of the vote is below 20 points, only three have proportional voting systems.

This contrast is no accident. Proportional voting systems have low barriers to entry. New parties typically need only 5% or so to elect members to parliament. This has helped the Greens, the far right and fervent socialists in various countries, notably Germany and Sweden. National politics is apt to become fragmented.

In some countries the centre right has also seen its support leak to smaller, often nationalist parties with few friends on the rest of the political spectrum. This is why the diminished centre left remains in power in Spain, Denmark and Sweden despite winning far fewer votes than a generation ago. All in all, assembling governing coalitions is becoming a harder, and often longer, process in a number of democracies.

First-past-the-post countries erect higher barriers to entry. Minor parties with evenly-spread support tend to be crushed in general elections. Ask Britain’s Liberal Democrats (12% of the Britain-wide vote in 2019; 2% of the seats) or UKIP (13% of the vote in 2015, just one seat). FPTP helped to thwart Oswald Mosley’s fascists in the 1930s, the National Front in the 1970s and the British National Party in the 2000s. FPTP can be unfair to friend and foe alike.

Of course, not all British elections are first-past-the-post. The SNP’s growth has been helped by proportional voting for the Scottish parliament. The party came to power in 2007 at the head of a minority government, even though its contingent of MPs at Westminster remained small because of FPTP. But the momentum gained by the SNP taking office at Holyrood reached its spectacular climax in the 2015 general election, when the party won 50% of the Scotland-wide vote and 56 out of 59 MPs, while Labour, down to 24%, lost 41 of its 42 seats. Suddenly, Labour and not the SNP became the victim of FPTP.

What, then, can Labour do across Britain? It has recovered from disaster before – such as when it climbed back from 28% in 1983 to 44% and Tony Blair’s landslide victory in 1997. Perhaps the best lessons from the 15-country survey are to be found in the countries where progressive parties have done best.

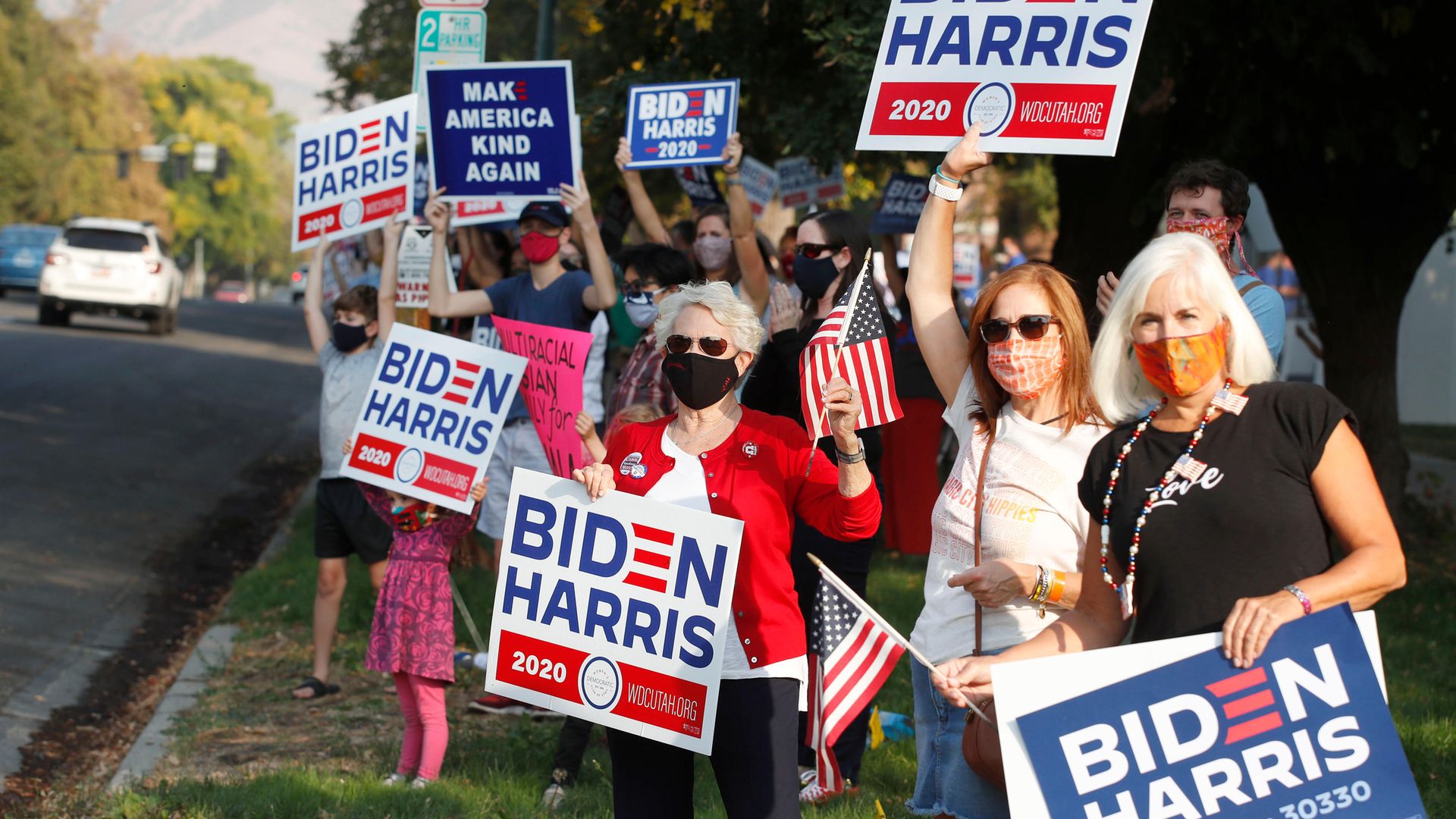

In the United States, Joe Biden has started to win back traditional Democrat voters in the rust belt. His party has also consolidated his support with black voters. However, in some parts of Florida and Texas, Hispanic voters have been drifting to the Republicans. There may be uncomfortable parallels for Labour. As Trevor Phillips recently observed in the Times, the Tories seem to have gained votes in this month’s elections from people of Indian and Sikh heritage in West London.

These demographic changes may be hard to reverse. Indeed they could be welcome: is it not better for votes to be driven by economic and social values, rather than ethnic or religious identity?

US Democrats’ have also marginalised small parties, such as the Greens. Entry to the big time is hampered by the vast cost of fighting elections, not just the voting system. Money helps to preserve the Democrat-Republican duopoly.

There is, though, another Democratic advantage that has lessons for Labour. America’s women are strongly Democratic. They voted for Biden by 57-42%, while men backed Donald Trump by 53-45%. In Britain, the gender gap used to run the other way: women were more Conservative than men. That has now been reversed; but the gender gap in Britain is far smaller than in the US. If Labour could match the success of the Democrats among women, especially in the suburbs, this could make a significant contribution to the party’s revival.

In Europe, Portugal’s Socialist Party has kept the Greens and communists at bay, and built a record for pragmatic and effective rule. It managed to brush off a decision in 2018 by Pedro Santana Lopes, one of its former prime ministers to break away and set up a new party, the Alliance. This won less than 1% of the vote the following year (just like Alex Salmon’s Alba party a few weeks ago).

New Zealand also has lessons for Britain. Until 1996, it was an FPTP country. Its politics were broadly similar to Britain’s, with alternating periods of centre left and centre right government. In 1993, the country voted to change to proportional representation. This could have produced a flowering of minority parties – and, to a degree has. The Greens have won seats at every post-1996 election, while New Zealand First, a nationalist party, have won seats at some of them.

However, the two big parties, Labour and National, have continued to dominate elections. In power, Labour has governed from the centre (even sometimes edging to the right, notably in the 1980s when its embraced liberal economic policies known as “rogernomics” after its then finance minister, Roger Douglas). However, it has also sustained its base.

Since returning to office in 2017, initially as a minority government, it has raised the minimum wage by 21%, scrapped apprenticeship fees and helped less well-off New Zealanders in other ways. Labour’s electoral coalition has held firm; and its leader Jacinda Ardern gained credit in last October’s election for keeping the country almost completely clear of Covid. All this shows that proportional voting presents challenges that the centre left can overcome.

A survey of this kind cannot do justice to the full variety of national, economic and demographic differences around the world. Erven so, it is clear is that Britain’s Labour Party has much to learn – and much to fear. Our electoral system has helped it to remain competitive, while many of its sister parties have shrivelled. However, as Scotland showed in 2015 (and the Liberals discovered in the 1920s), FPTP cannot ultimately save a weak party. If Labour fails to revive, its eventual collapse could resemble Earnest Hemingway’s account of bankruptcy: coming “gradually, then suddenly”.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk