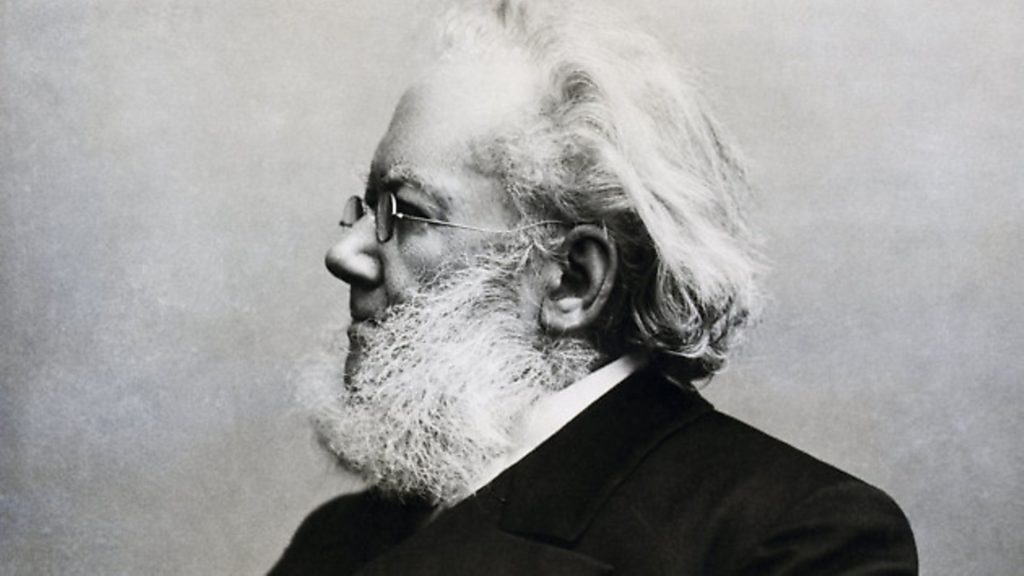

Henrik Ibsen is credited with creating modern theatre. He did so by asking questions we’re still trying to answer

Nothing was too personal for the man described as father of modern drama. From tales of sexually transmitted diseases (Ghosts), bored housewives (Hedda Gabler) and debt and blackmail (A Doll’s House), at the heart of a Henrik Ibsen play is a scandal that wouldn’t be out of place as a Netflix series or a newspaper front page. Yet, in spite of these unhappy marriages and family secrets, much of the Norwegian playwright’s oeuvre pivots around a human desire for freedom of expression.

When Ibsen’s iconic heroine Nora walked out on her husband and two small children at the end of A Doll’s House in 1879, her slam of the door sent shockwaves through audiences of the time.

The play was welcomed by contemporary feminist thinkers across Europe, despite Ibsen declaring in a speech to the Norwegian Women’s Rights League in 1898 that he wasn’t even ‘quite clear as to just what this women’s rights movement really is’.

Ibsen’s concern was with the human soul, but whether a feminist or not, his work certainly garnered attention for its support of women’s rights: ‘a woman cannot be herself in contemporary society,’ he once noted ‘with laws drafted by men, with counsel and judges who judge feminine conduct from the male point of view’.

Anyone who has made it past their mid-twenties will be undoubtedly familiar with the ‘when are you getting married/ having children’ line of questioning. Women aren’t all created to be mothers, said Ibsen in his notes to A Doll’s House, but more than 130 years on, whilst marriage is arguably less important in a secular Britain, to live an unmarried or childless life is still taboo enough to provoke comment.

If the Victorian reaction to an attack on the institute of marriage in A Doll’s House was one of outrage, it was trumped by the publication of Ghosts which the playwright modestly anticipated ‘would cause alarm in some circles’. Performance was banned in Britain and other countries – syphilis and attacks on religion did not go down well in Victorian society it seems, and the play was labelled ‘revoltingly suggestive and blasphemous’ by critics.

As one of the most-performed playwrights in the world, second only to Shakespeare, according to some counts, Ibsen’s contribution to not only Norway’s but Europe’s cultural heritage is vast and he is credited with the birth of modern theatre as we know it.

Back in the 19th century, stage actors would perform with an air of melodramatic grandeur in front of painted backdrops – far removed from the everyday speech and household scenes of reality.

But, as James Joyce said, ‘Ibsen’s plays contain men and women as we meet them in real life, not as we apprehend them in the world of faery’. They talked about real issues in a recognisable way.

This ability to speak to the human condition and transcend the era in which it was written is what makes a playwright’s work endure: Shakespeare can uncover things you didn’t know about yourself. And decades after they were written, some of Harold Pinter’s works still instil the terror of an intangible menace in society.

A radical both politically and personally, Ibsen was no stranger to the themes raised in his work. Born in Skien, in southern Norway, in 1828 to a wealthy middle class family, his father suffered bankruptcy when Ibsen was a child.

Aged 18, a world away from the father and husband he was to become, a relationship with a maid servant ended with a pregnancy that could have shaken the teenage Ibsen’s reputation, but a fear of scandal meant he disowned his first son, Hans Jacob.

The shock factor clearly wore off though, as at 61 years old, the now famous – and married – playwright met and fell in love with 18 year old Emilie Bardach. But his guilt at infidelity eventually put an end to this and any further relationships with youthful admirers.

A true European, Ibsen wrote his plays in Danish and lived in Norway, Italy and Germany – in fact most of his major work was written away from his homeland, in Rome, Dresden and Munich.

Written in 1850, Catilina was his first play and, a year later, aged 23 he became resident playwright at the now defunct Norwegian Theatre, in Bergen, a position he held until 1857. But these initial works weren’t well received and it wasn’t until more than 30 years later that his drama of ideas gained international recognition.

A clue to his appeal can be found in these problem plays – A Doll’s House, Ghosts, An Enemy of the People. Ibsen asked questions rather than giving answers, allowing the text an ability to change shape to fit pertinent topics, ensuring their continued performance not just in Europe, but worldwide.

The most recent of Ibsen’s heroines to hit London’s National Theatre, Hedda Gabler exists in a dichotomy between breaking convention and a dread of disgrace.

Ultimately for Hedda, the torment of this psychological prison is too much to bear. There is still something troubling that we recognise in this and other Ibsen plays as a very modern problem – the pressures of a society which thrives on scandal, while pushing unattainable standards of perfection. In this way, Hedda is a very modern woman.

Daisy McCorgray is a freelance journalist and writer________________________________Review: Hedda Gabler at the National TheatreIn his National Theatre debut, Belgian director Ivo van Hove creates a compelling modern production of Ibsen’s unstable anti-heroine.

Conventional life is death for Hedda, and Van Hove focuses on her staid marriage – in which she plays second fiddle to the artefacts and field trips of her academic husband, played by Kyle Soller.

As we know from Ruth Wilson’s roles in Luther and The Affair, playing troubled, volatile characters is what she does best, and Hedda Gabler is no exception.

From the opening moment slumped across the piano centre stage, Wilson’s Hedda captivates with her catty retorts and destructive acts. As she burns manuscripts, and beheads bunches of flowers, she battles with herself as much as the yawn-inducing dullness of new husband Tesman.

Hedda states: ‘I will not make something that makes demands’. Yet allusions to this unborn child and Wilson’s inability to escape the stage act to fortify her despairing sense of confinement – literally represented when Rafe Spall’s sinister Judge Brack boards up the only window on Jan Versweyfeld’s minimalist set – and destroy any attempt at autonomy.

While Ibsen’s is a morbid tale, aside from a somewhat unnecessary dousing of Hedda in blood, the production succeeds as a striking and relevant vision of relationships and the social pressure to achieve.

Hedda Gabler will be broadcast by NT Live on 9 March 2017.