Patrick Sawer on a new book which underlines the extraordinary closeness that The Clash used to enjoy with their fans.

In his eulogy to the exuberant heyday of music papers, the Ulster singer and critic Gavin Martin tells his audience, no doubt digitally-native youngsters enthralled by tales of the golden age of rock, that he pities them.

The reasons are clear and compelling.“You never saw The Clash or slept on Strummer’s floor,” Martin tells them.

In that neat couplet, from his 2017 song I Want To Tell You Something, Martin encapsulates the life of a music fan, not only enthralled by the spectacle of his guitar heroes, live on stage, but sometimes lucky enough to rub shoulders with them in the most mundane, but deeply significant of ways.

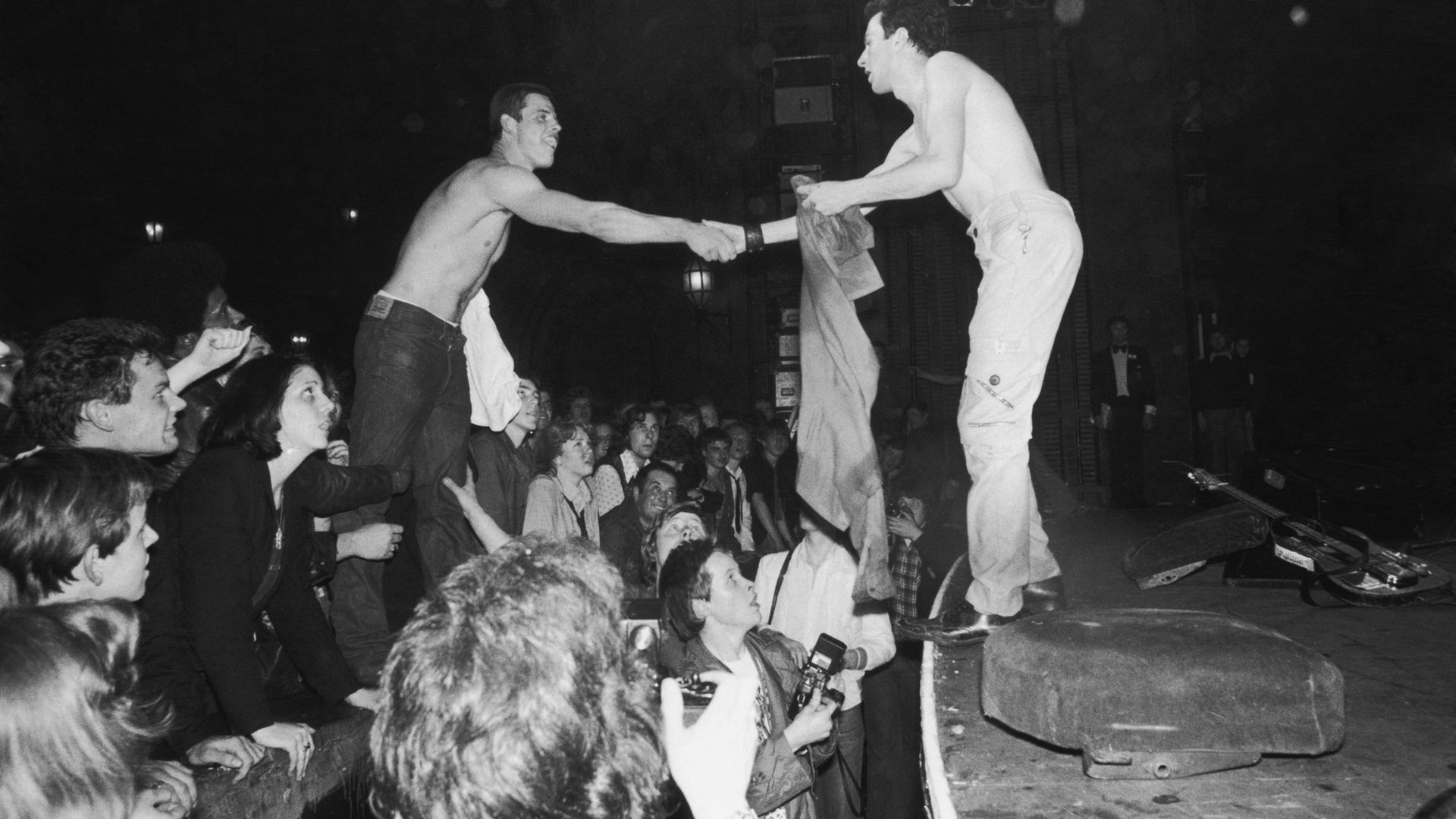

The Clash were among that small group of bands who turned the experience of being a fan into that of being a member of the same gang – not only following them around the country, but being encouraged by the likes of singer Joe Strummer to bunk into their gigs for free and crash on their hotel floors for the night.

It was this relationship – and Strummer’s genuine and abiding interest in the lives of the band’s fans – that lifted The Clash above ordinary rock stars and made them at once both just like us and ‘the only band that mattered’.

The phenomenon is captured beautifully in a book by the pop culture writer Tony Beesley, which chronicles the relationship between The Clash and their fans, told through the words of those who bought their records, pored over their lyrics and for whom, like me, listening to them was an education from a bunch of older, way cooler, brothers.

There has been a tendency among some fans of the band to mythologise The Clash and worse, sanctify ‘Saint Joe’ – particularly after his death at the age of 50 in December 2002. He would have hated that. A humble figure, he preferred face to face conversation to adulation from a distance.

And it is to the credit of this book that it captures that euphoric essence of the band; the idea – fundamental to punk – that anyone could pick up a guitar and play and that everyone has a story worth listening to.

It was something that Strummer firmly believed in, as many of the figures quoted in the book testify, though he was not completely unique in this. His own idol Woody Guthrie, the great American folk singer – who the young Strummer was nicknamed after – had a similar view, seeking out the oral testimony of the subjects he met on the road.

Beesley has spoken to dozens of now ageing punks who say the same thing – that Strummer and the band not only went out of the way to listen to them, but wrote about their lives and concerns, their dead end jobs, their run down tower block homes, their petty-tyrannical bosses, their suburban ennui, their frustrations, and crucially – adding a dash of romantic rock and roll mythology along the way – elevated those experiences into universal themes.

Early in the book, Cathy Cooper, now a photographer and one of Strummer’s friends from his days in Newport, South Wales, describes their first meeting at a student union dance in 1973.

“He was like no other man I had ever met. He asked questions and listened intently, sometimes making notes,” she says. “For example, we were in a pub one night called The Angel and he asked me why I never wore a skirt. ‘I like trousers’ I replied. He got out his notebook and wrote that down.”

(Is it fanciful to think this conversation found fruit a few years later in Strummer’s famous punk dictum “Like Trousers, Like Brain” – the notion that your clothes illustrated a state of mind?)

Another fan, Gary Crowley, who went on to become a professional DJ and broadcaster, remembers interviewing the band at a cafe near The Clash’s Camden rehearsals studio, for the fanzine he had set up, The Modern World (punk was nothing if not Do It Yourself).

He says in the book: “Joe’s warmth and time for us that day has always stayed with me. He patiently answered a barrage of questions. And he genuinely seemed interested in what we, ourselves, had to say. What our views were and who we were listening to.”

It was that curiosity about the word around him which fed into Strummer’s music and the band’s world view, and in turn was fed back to their fans in song references and interviews.

When Strummer or his songwriting partner Mick Jones namechecked the reggae artist Dr Alimantado or recorded a groundbreaking punky-reggae version of Junior Murvin’s classic Police and Thieves, countless young punks went out and bought the original versions.

When The Clash paid tribute to early New York hip-hop in The Magnificent Seven, we tuned into the Sugar Hill Gang and Grandmaster Flash. Indeed the band’s own musical journey across their five albums (nobody really counts the sixth) provided a genre-bending adventure before the term ‘world music’ was even invented.

The band provided not only a musical education, but a literary and political one. Strummer was an avid reader and his selections would feed into fans’ reading lists, whether it was the work of the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca, a biography of the 1950s Hollywood idol Montgomery Clift or a history of black American doo wop singers.

As to their politics – neatly summed up by Strummer when he declared “we’re anti-fascist, we’re anti-violence, we’re anti-racist and we’re procreative. We’re against ignorance”– their appearance at the April 1978 Rock Against Racism carnival in Victoria Park, east London, was a game changer, helping to put an end to punk’s superficial flirtation with fascism and drawing many a white teenager away from the far right National Front at a time when the party was threatening to break through into mainstream electoral politics.

Not that The Clash didn’t get it spectacularly wrong on occasions. Visiting Northern Ireland in 1977 the band posed in front of a British army checkpoint. It may have looked edgy and rock and roll back in London, but to many teenagers living in the region it felt as if their idols had become trouble-spot tourists.

Brian Young, who went on to form the Belfast punk band Rudi, told Beesley: “To his credit, Mick Jones was brave enough to point out in later years that the band felt like ‘dicks’, highlighting just how corny and insensitive those photos really were.”

Similarly when a group of Italian fans wrote to Strummer urging him not to glamorise or lend support to the Red Brigade by wearing a T-shirt with their five-pointed star logo, he paid attention and apologised, saying he hadn’t fully appreciated what the terror group was doing in their home country and the damage it was doing to any prospect of genuine left-wing reform.

The sense that in listening to their fan base Strummer and the band stayed true to the spirit of punk runs through this engaging book.

It is in part for that reason that the band remains so dear in the affections of ageing music fans, providing an example of behaviour worth emulating, and why a new generation of musicians willingly cite The Clash as an influence – even if only because their mums and dads played their records to them as children.

It is not uncommon to hear people say, as soon as you get onto the subject of The Clash and Joe Strummer, that “they changed my life”.

As Beesley says in his book: “The Clash, for me, are more than just a band; they are an ideal, a positive life-force that continues to inspire, influence, educate and excite in a multitude of ways. I cannot imagine the last 40-plus years without them in my life.”

- Ignore Alien Orders: On Parole WIth The Clash, by Tony Beesley and Anthony Davie, is published by Days Like Tomorrow Books

- Patrick Sawer is a senior reporter with The Daily Telegraph and Sunday Telegraph