Inspired by former glories, supporters wanted change, even if it was a leap into the unknown, as it all backfires there are striking political parallels.

Perhaps the most noteworthy achievement of Ipswich Town Football Club over the last season, other than being relegated from the Championship, has been that it has provided the world with a decent metaphor for populist politics.

A year ago, towards the end of the 2017/18 season, dissatisfied with their lot, the Ipswich fans spoke – raged, even – at how stagnant their club had become. This once great institution had been going nowhere for a long time. Things weren’t awful. But the fans – as fans always will, especially those who remember winning trophies – wanted something better.

It doesn’t take too much of a leap of imagination to compare that state of affairs with how some saw the UK – a big past, a bit mediocre now, not really going anywhere – in the run up to the 2016 referendum.

So the Ipswich fans complained and their voice carried weight. The club listened and changes were made. The result was a dreadful season of terrible results which ended in relegation to League One.

The fans’ dissatisfaction was justified. Ipswich Town is a club that has been going nowhere for most of this century. No English club, apart from the usual suspects at the top of the Premier League, had seen less movement in their league status over the last 17 years than Ipswich, a club which has spent almost all of the 21st century anchored in the untroubled mid-table waters of England’s second tier. For years – and it felt like decades – Ipswich Town Football Club has been mediocre.

This mediocrity reached its nadir in the five-and-a-half years before this season. These were the Mick McCarthy years, a manager whose cautious, defensive approach made the club’s tedious consistency seem immutable, as permanent a feature of East Anglia as the River Stour, the River Orwell or the River Gipping.

As a neutral spectator who regularly watched Ipswich during this period, I took a perverse delight in just how dull Ipswich became under McCarthy; paying to go and watch Ipswich you were paying to watch football that was largely devoid of alarms and which contained no surprises.

Suffolk is flat, the North Sea is cold and grey, and Ipswich Town Football Club wasn’t going anywhere. There was something comforting about the fixed ordinariness of it all.

But I was a neutral and therefore was never caught up in the sentiment that makes football what it is. Without the sentiment of fans, football would play a comparable role in culture to that of water polo or croquet – the competition may be fierce, but no one would give a toss.

It is sentiment that keeps football’s whole daft circus trundling on. It is what makes fans travel hundreds of miles in ancient coaches with brushed nylon seats and Formica interiors, vehicles that still somehow stink of diesel and stale Ginsters, just so they can stand in the cold and the rain so as to watch their team lose. It is sentiment that makes football fans sing terrace songs as depressing as ‘Swindon ’til I die’.

But, and I apologise in advance for being a hard-headed rationalist about all this, football isn’t entirely about sentiment. It is also about who scores the most goals. So, if you were not caught up in the sentiment of being a Tractor Boy, you could argue, if you looked at the results and the money that the club spent, that McCarthy did a good job.

He built solid and reliable teams on a tiny budget. He even managed – and this was one of the club’s few 21st century adventures – to get Ipswich into the play-offs in 2015, something he did with a team that cost only £110,000. Unfortunately, Ipswich were defeated in these play-offs by arch rivals Norwich. The Canaries got promoted and Ipswich went back to where they are most comfortable.

It may have been this play-off defeat that turned the fans against McCarthy. Or it may have been any one of dozens of tedious Saturday afternoons or Tuesday evenings at Portman Road. Or it may have been when, in the late winter of 2018, McCarthy seemed to shout ‘f*** off’ at the Ipswich fans after a late equaliser from Norwich City in another Old Farm derby game.

So the frustrated fans (who probably needed to do something – anything – to stop being bored) demanded change. They did this in the traditional ways, some on the terraces and others by simply not going through the turnstiles. But they also did it on the internet, in chatrooms, on social media, in podcasts. Amplified by the online world, they made their voice heard and it was this collective voice was that allowed to shape the future of the club.

Intriguingly, you can trace the development of social media back to football chatrooms around the turn of the century, as fans moved their moaning from the terraces and the pubs online. In the history of the internet, and the shaping the culture of the web, football chatrooms are right up there alongside the monetising of porn sites and the self-absorption of the blog as being the well from which so much has sprung.

One example of the chatroom’s contribution to world culture is the internet word ‘troll’ as in spiteful, irritating git. According to some, this came from football chatrooms where rival fans would ‘trawl’ for a response by making provocative statements. More importantly, there is no question that the internet has amplified dissatisfaction, justified or not, to a deafening level. It’s not hard to see, in a world where people get their news from social media, why this can be dangerous.

So at the start of this season, the Ipswich fans got their way and dull old, trusty old Mick McCarthy was replaced as manager by the young, ambitious, but inexperienced Paul Hurst. How must the uber-cautious Mr Measured McCarthy have felt about that decision; a decision that went against the very nature of McCarthy’s entire being?

Not only had he lost his job but he lost it as a result of the first reckless decision made at Ipswich Town Football Club in years. But it doesn’t matter what he felt, he moved on to manage the Republic of Ireland and to doing what he is good at: grinding out one-goal victories against Georgia and Gibraltar. The important thing here though was that life surged back through Ipswich Town Football Club.

Things were going to change.

And change they did. The biggest change is that Ipswich finally escaped mid-table Championship mediocrity by being relegated. Ipswich won only one game in their first 17 matches and Hurst was sacked in October 2018, when the more experienced Paul Lambert was bought in. He also failed to keep the club up. It doesn’t take too much of a stretch of imagination to compare this state of affairs with what happened after the Brexit vote. Few would argue that the people’s voice has made the country a better place.

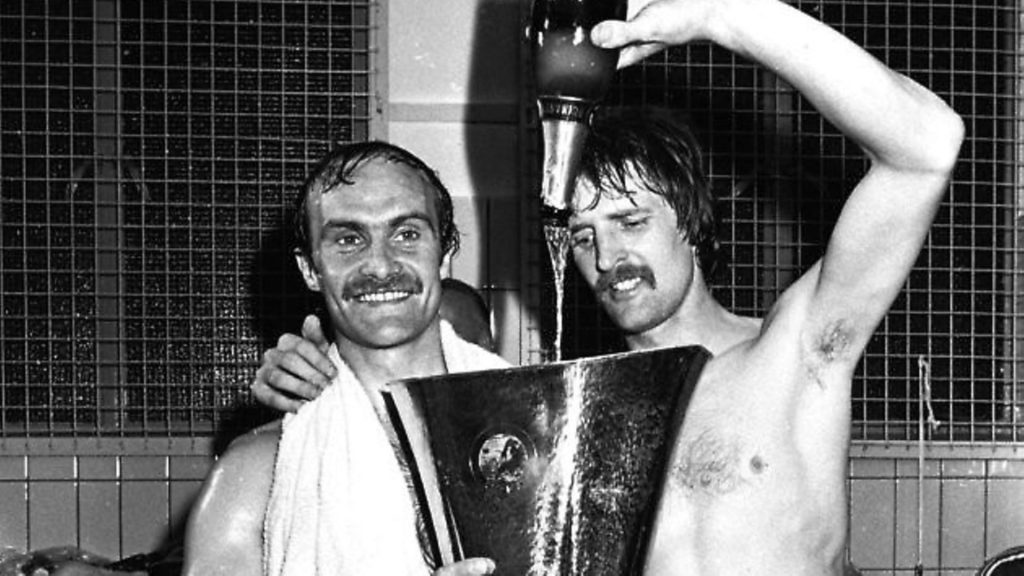

Ipswich will kick off next season in English football’s third tier – a place the club hasn’t seen since 1957, since Alf Ramsey took them from lower league anonymity into Europe, something that Bobby Robson would do again in the late 1970 and 1980s. The club with a huge past – that once faced AC Milan, that once beat a Saint Étienne side captained by Michel Platini, and who then went on to win the UEFA Cup – are now looking forward to a season playing Fleetwood, Shrewsbury Town and Lincoln City.

And it is now where this ‘relegation as populism’ metaphor hits the back of the net. Ipswich have now left the Championship and, as we know, irrespective of the insistent demands of reality, ‘leave means leave’.

Yet many Ipswich fans are not especially downhearted by this relegation and about their leaving the years of Championship mediocrity behind them. There is even a hint of the ‘hard-Brexit now’ stubbornness in their response. The head of their supporters’ association recently said that the football was better this season, which, seeing as the point of football is to score more goals than your opposition, is certainly an interesting way of looking at it.

But there is more to this than just a glib point about how Ipswich brought disaster upon themselves. One of the defining features of public discourse in the 21st century has been how the internet and social media is something that has amplified opinion in a way that now means that it has the ability to break things and to stop things working properly; British economic policy, the working of parliament, the EU, the functioning of American government, all stand alongside Ipswich Town Football Club as institutions where the online voice of the people – or the opinions of the people – have arguably made things worse.

This elevation of opinion to the level where it is able to have such a negative impact sits at the heart of modern politics and modern social discourse. Of course, in the case of football it does not really matter (the whole joy of football is that it doesn’t really matter). But elsewhere it does matter.

As such, populism and the existence of the court of public opinion raises profound questions about the nature of democracy at the start of the 21st century. The key issue of Brexit has now settled on Thomas Hobbes’ question, formulated in the 17th century, as to whether an MP owes the electorate his judgement or his loyalty to their opinion.

Today we can repose that question as ‘should we be governed by the judgement of our elected officials or by the wisdom of the comments section or Twitter’. This question is at the centre of the social contract that lies at the heart of our political system and Brexit may not ever really be resolved until that question is resolved. But getting back to football, we could, just for the political-economy bantz, argue that McCarthy at Ipswich was the Thomas Hobbes of football management. He didn’t much like change, he kept things steady and his ‘contract’ with the fans was that they should support his choices.

But, in the spirit of that other great shaper of modern politics Tom Paine, East Anglia’s great 18th century revolutionary, the Ipswich fans broke that contract and, in doing so, Ipswich got relegated. (Tom Paine was from Thetford so would probably have supported Norwich and would have therefore been chuffed to have added ‘got Ipswich relegated’ to his other achievements of ‘helping invent the USA’ and ‘overthrowing the ancien régime’).

The rational part of me, which sees football as being about scoring the most goals, sees Ipswich’s relegation as a fairly daft example of the sorry triumph of populism. However, I’m vaguely aware that there is something about this that I don’t quite understand, something I’m not privy to because I’m not a Tractor Boy and I’m not governed by sentiment when it comes to that club’s fortunes.

It may just be the case that the disaster of relegation is, for the fans, really, genuinely, better than watching Ipswich grind out another tedious 1-1 draw with Hull. As that other great political theorist Sir Bobby Robson put it, football is about ‘the noise, the passion, the feeling of belonging’. And Sir Bobby knew more about football – and Ipswich Town – than Hobbes and Paine and me combined.