From the days of his grandfather – a British army general who trained the IRA on his estate – Cathal Ó Gabhann’s fascinating family history has been entwined with the Irish border. In this powerful essay, he looks back at the past and reflects on what Brexit means for the next generations.

Much has been written about ‘the Irish Border’ in the past three years, to the extent that it now even has its own Twitter handle (@BorderIrish). Nancy Pelosi, the House of Representatives speaker, has talked about it, warning that there would be no post-Brexit trade deal with the US if the British government imperilled what she called “the seamless border between the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland”. And yet this wriggling line which gerrymeanders its contrived way across Ulster – separating the province’s counties of Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan in the Republic from their six siblings in the UK – remains deeply misunderstood by those across the Irish Sea, not least by the current Westminster cabinet.

I have been fascinated by this enforced feature of Ireland since I was a child. For five generations – of which mine was the last – my family lived at Bellamont Forest, an 18th century Palladian villa on a thousand-acre estate straddling the boundary between Counties Cavan and Monaghan, just 11 miles from the border. Characterized by drumlin hills, forests, river systems and crannóg-dashed loughs, this part of the country is seen by many as a backwater; but for the angler, shooter or huntsman it represents a rural idyll. In 1980, when I was a year old, my parents uprooted to north east England. We moved there because of the border.

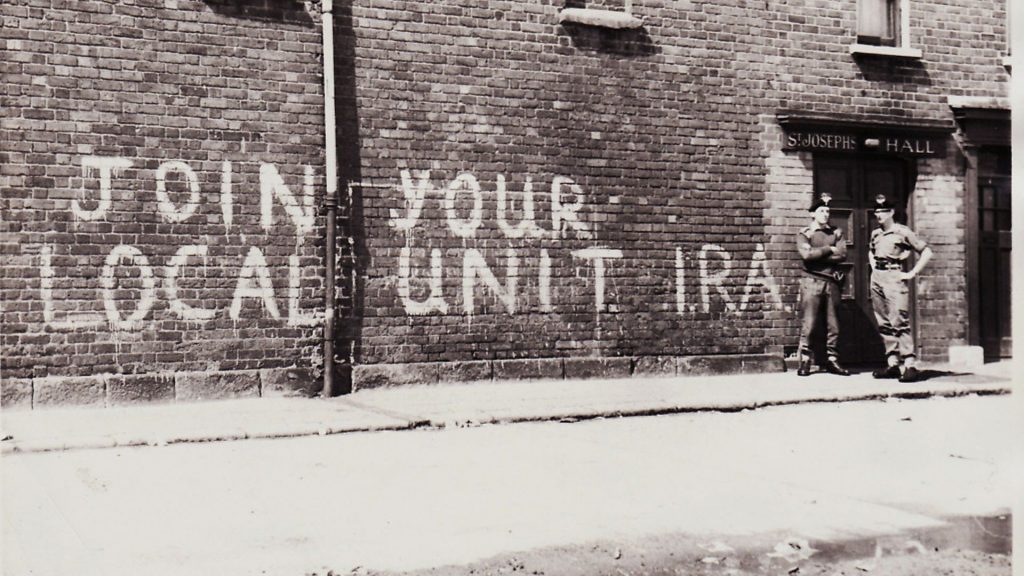

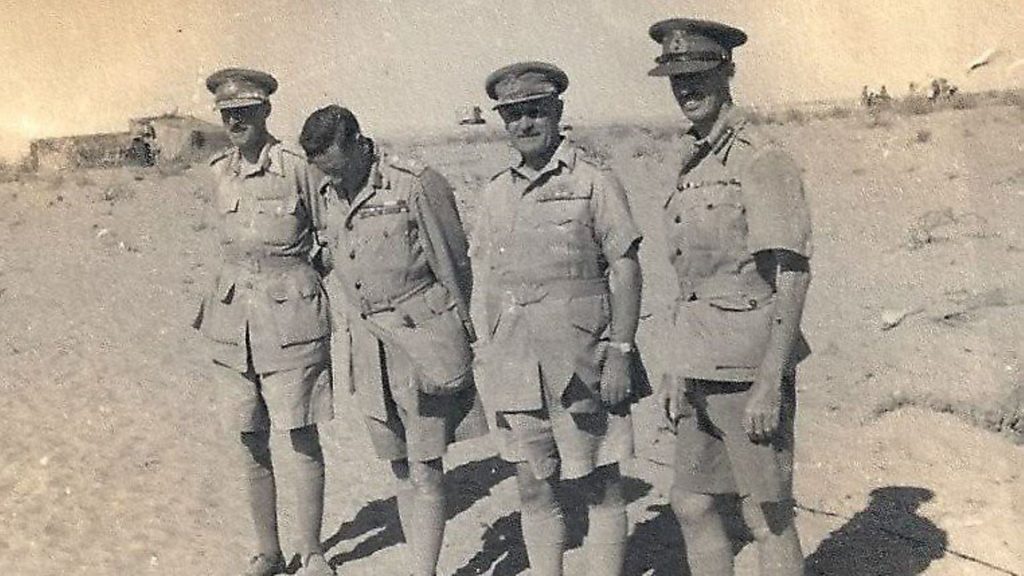

My recent family history is intertwined with that of the border. In the lead-up to the 1920s Irish War of Independence (which ended with the border’s creation) a member of staff at my great-grandfather’s home, Bellamont Forest, siphoned ammunition from the gun room to the local IRA unit; a year or so later, with that war in full sway, my grandfather – then a young British army officer – assisted IRA volunteers in burying a cache of grenades on the family estate.

Three decades later, during the IRA’s border campaign known as Operation Harvest, my grandfather – by then a retired British army general – advised and trained IRA volunteers at Bellamont.

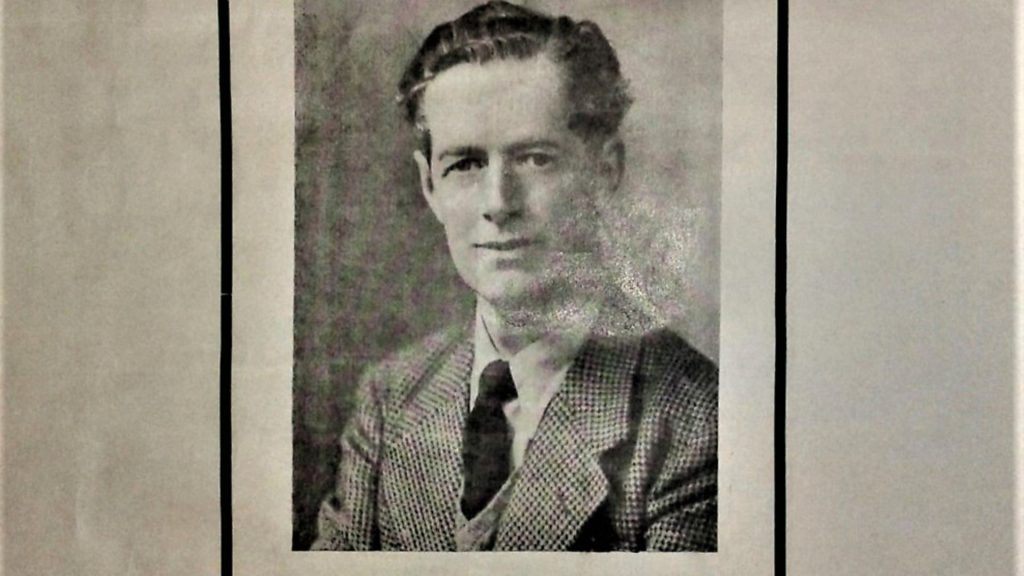

My grandfather died in 1969, in the same year that my father, a Benedictine-educated Gaeilgeoir or Irish speaker, followed him into the British army. As a subaltern, he was one of the first pairs of boots onto the ground in Belfast exactly 50 years ago, as Operation Banner began.

Assigned to protect Catholics from sectarian violence, he saw little contradiction in carrying a rifle for the British just two hours’ drive from his home in the Republic.

But as the violence – known by some as the Troubles, and by others as the Long War – gradually hacked away at lives and communities from Derry to Guildford, my father returned to Bellamont Forest and attempted to stay out of it.

In 1974, the Ulster Volunteer Force detonated bombs in both Monaghan town and Dublin, killing 33 civilians and wounding around 300 more. I was six months old when the IRA killed Viscount Mountbatten in Sligo and 18 British soldiers in an attack on the other side of the country on the same day.

The situation was increasingly tense, and my father’s refusal to fulfil the role for the Provisional IRA which my grandfather had performed for its predecessor rendered our continued presence in Ireland impossible. In 1980, we left Bellamont behind, and settled into exile on another border, in the wild countryside of Northumberland.

We visited our old family home sporadically during the 1980s and 1990s. Taking the ferry from Stranraer, we would cross over to Larne and drive through the North down to the border. As a young boy, the non-stop drive south was an adventure.

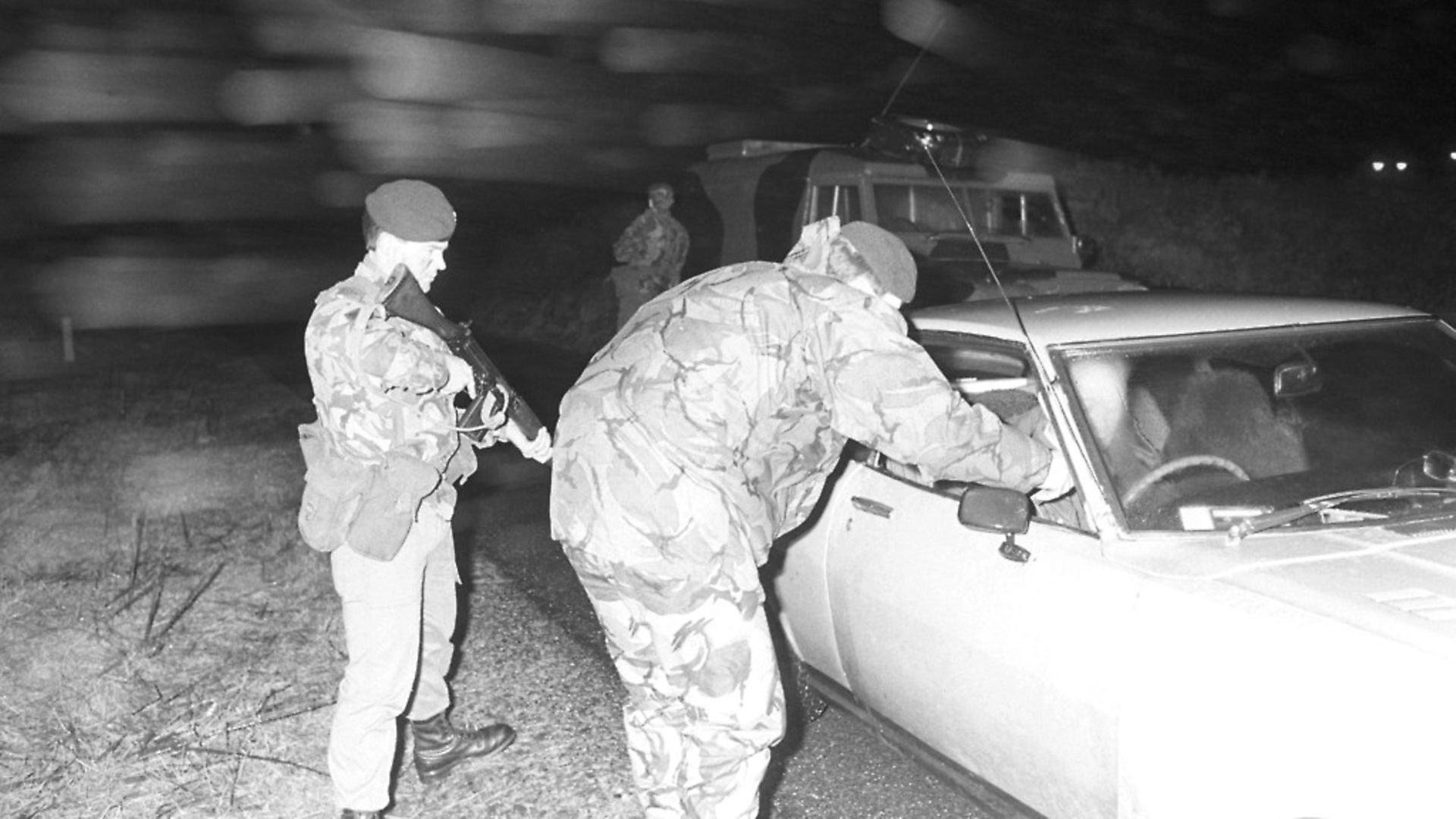

The checkpoints; the watch towers; the grey Royal Ulster Constabulary Land Rovers; the helmeted soldiers manning machine guns behind sandbagged sangars; all left a deep impression on me. Helicopters flew overhead as the Ulster Defence Regiment would rush past in camouflaged Land Rovers to block the road and check drivers’ identities.

As we approached the border, I was mystified by signposts pointing down winding country lanes labelled “Crater”; my father would avoid those as we were funnelled into a checkpoint surrounded by imposing gunmetal blast walls.

Compared to the securitised North, I found the rural counties south of the border mundanely relaxing. We would walk, swim and fish. Although we never caught anything, there was always the promise of a giant pike lurking in the depths of the many expansive loughs which punctuate the counties on both sides of the border.

I was too young, then, to understand that Monaghan was – as it remains – a Republican stronghold. In 1986, Séamus McElwain, a 26-year-old Monaghan man (whom, to this day, DUP leader Arlene Foster holds responsible for the attempted murder of her father), was killed by the SAS while manning a roadside IED in the neighbouring county of Fermanagh.

A year later, the SAS killed Jim Lynagh, a former Monaghan town councillor, along with seven other IRA volunteers, while they were attacking a RUC station in the other neighbouring county of Armagh in an operation which sought to emulate a strategy of borderland ‘liberated zones’ first articulated by my grandfather 30 years before.

Even in my grandfather’s time, Monaghan native Feargal Ó hAnnluain died alongside Seán South in the ill-fated 1957 Brookeborough Raid in County Fermanagh. That venture inspired the song The Patriot Game, from which Tom Clancy later took the title for his novel-turned-film, set during the Troubles.

Unlike most any other frontier in Europe, the so-called ‘Irish’ border – forced upon the fledgling Free State government under threat of “immediate and terrible war” by the British government in 1922 – does not separate two countries or peoples, nor follow the natural topography of mountains or rivers, but divides the country and people of Ireland into two so as to ensure a Northern Protestant majority under British rule. It would be far more accurate to refer to ‘the British border in Ireland’, or simply, ‘partition’.

This summer, I once more found myself in County Fermanagh, in the very spot where Séamus McElwain was killed. His brother Seán – a representative of the Republican ex-prisoner group Clones Fáilte – showed me where the IED was placed, and where Séamus and his colleague, Seán Lynch, were when the SAS opened fire (Lynch survived, and went on to become an elected member of the legislative assembly of Northern Ireland).

Seán McElwain pointed out the field in which Séamus had lain, wounded, while the SAS soldiers interrogated him for several minutes before shooting him dead. I saw where Feargal Ó hAnnluain and Seán South died from their wounds 30 years prior to that incident, and visited the house in which the remainder of the IRA’s Pearse Column had sought refuge. And I was crossing the invisible border from Monaghan into Armagh on August 19, when a voice on the radio announced that an IED in Wattlebridge, County Fermanagh, had just targeted police “with intent to kill”. Driving through Belfast later that same day, I took a wrong turn and found myself in a street flanked by row upon row of the purple and orange flags of the UVF; a reminder that Loyalist paramilitaries, too, still exist today.

The great success of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement was in removing the checkpoints, watch towers, helicopters, machine guns and, of course, the IEDs. Communities separated for decades by a border hardened by British army-cratered and barricaded roads, could once again return to a peaceful rural life.

For the past 20 years, farmers in Fermanagh have been able to tend their fields in Monaghan, and parishioners in Monaghan to reach their churches in Fermanagh, using hedgerow-bound roads no different from those in rural Northumberland. Mundane tranquility has returned as the security apparatus has faded into memory. It is as if the border has ceased to exist.

But exist it still does. The GFA may have removed the border from the topography, but it remains a cartographical reality. For many local inhabitants, the GFA transformed the border from a practical aggravation to a political anomaly; unjust but eventually surmountable, with the momentum of history on the Republicans’ side; a stop-gap solution on the road to Irish unity.

It is natural that the people of Donegal and Derry; Cavan and Fermanagh; and Monaghan and Armagh are nervous about the future. Against the background of a rejection by Westminster of the backstop, reassurances that there will be no return to a hard border ring hollow.

How can anyone systematically monitor the hundreds of tiny rural roads, criss-crossed by the border, without installing infrastructure for this purpose? How will beef farmers in the North continue to sell their produce to the Republic? How can a return to such surveillance of this contentious part of the world even be countenanced by any but those wholly ignorant of the pain and anguish which still lingers there – suppressed, but not forgotten? How can the backstop be denounced as “undemocratic”, when its purpose is to protect the GFA – which was voted for in a cross-border referendum of all the people of the island of Ireland?

In under three years’ time, the border will be 100 years old. Since its creation, thousands of men and women have killed and been killed due to its very existence. If there is a blessing in Brexit, it is that the absurdity of the border is once again being discussed – albeit that Republican voices are conspicuously absent from Westminster debates.

It is undeniably ironic that a border imposed upon Ireland by the British now presents an existential crisis for the UK. My grandfather recognised that Partition was inherently wrong for the people of Ireland but that it was also a strategic folly in the Cold War environment of the 1950s; an Achilles heel in the Atlantic Pact, exacerbated by the Irish Republic’s policy of neutrality. Sixty years later, the border – which will be the UK’s only land frontier with the EU – poses a direct threat to the British government’s promise to deliver Brexit. As almost 56% of people in those six counties of Ulster voted to remain in the EU, one has to ask if there is any further legitimate argument to support the continued partition of Ireland.

The courthouse in Monaghan town still bears the British royal coat of arms on its façade; and on the street in front of the building, a pillar box still sports the monogram of King Edward VII, albeit the original red now painted green.

These fossilized relics of the British empire stand testament to the success of the IRA of the 1920s in liberating 26 of Ireland’s counties, and are a lingering reminder that six of her counties remain part of the UK.

As the British government rejects the backstop and commits to leaving the EU by Halloween, it also commits to sabotaging the Peace Process, reneging upon commitments made in Belfast in 1998. In a further twist, in Belfast itself on Monday the Home Office won its appeal in the DeSouza case, an Upper Tier Immigration Tribunal ruling that – despite what is explicitly stated in the GFA – Irish nationals born and bred in the six counties are, by default, legally British subjects. Such an environment stokes the anger and grievances not only of ‘dissident’ Republicans, but ‘mainstream’ Republicans too.

The red-brick Palladian villa at Bellamont Forest – purported to be the finest architectural example in Ireland – still stands today. Originally built as a testament to the English Protestant ascendancy of the 18th century, then bought by my Irish Catholic great-great grandfather in 1874, over the past century Bellamont has been the backdrop to a war of liberation, partition, two campaigns to smash the border, and a peace process based on the principle of consent and enshrined in the GFA.

Bellamont now faces down the spectre of Brexit; but of all the ghosts which haunt this 300-year-old building, the border is surely the most persistent. And as the rumble of an explosion once more echoes over the drumlins and loughs of a partitioned land, the British government must recognize that the GFA is the only stop-gap solution to this century-old problem, and that continued peace in Ulster now hinges upon the backstop.