The film, which turns 50 this year, seems like the classic Brexit movie. But, says ROGER DOMENEGHETTI, there is another way of viewing it.

On the morning after the Brexit referendum in June 2016, as the shock result emerged, Daily Mail journalist Sarah Vine turned to her husband Michael Gove, who had been instrumental in the Leave campaign, and exclaimed: “You were only supposed to blow the bloody doors off!”

This invocation of the classic line spoken in The Italian Job by Michael Caine’s character Charlie Croker demonstrates both the film’s enduring appeal and the fact that at its heart lies an ambiguous depiction of Britain’s relationship with Europe.

At the time of its release in 1969, The Italian Job was just one in a long line of heist movies produced in that era. The popular and profitable sub-genre included films such as Topkapi, How to Steal a Million and even The Great St Trinian’s Train Robbery, whose title aped the real life robbery in 1963 that captured the imagination of the public and film makers alike.

However, over the last 50 years The Italian Job has risen above its contemporaries and has repeatedly been voted one of the best, if not the best, British film of all time.

Thanks to its bright paisley colour pallet and kitsch iconography the film has come to epitomise the Swinging Sixties, or at least an idealised version of the decade.

It was originally conceived by Ian Kennedy Martin as a television play set in London. When the BBC passed, he sold the rights to his older brother Troy, the creator of Z Cars, who re-purposed the script for cinema and moved the main action to Turin.

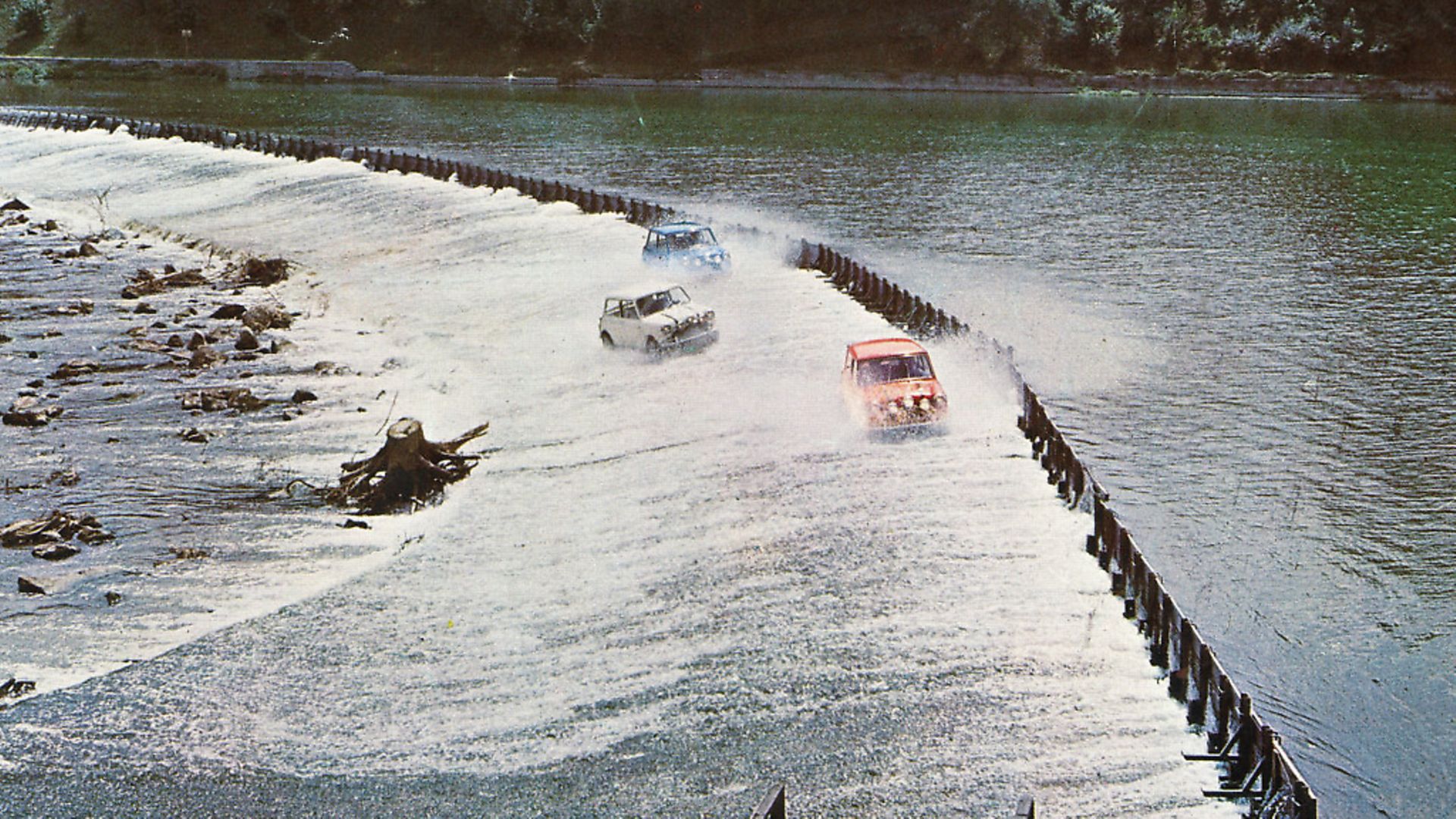

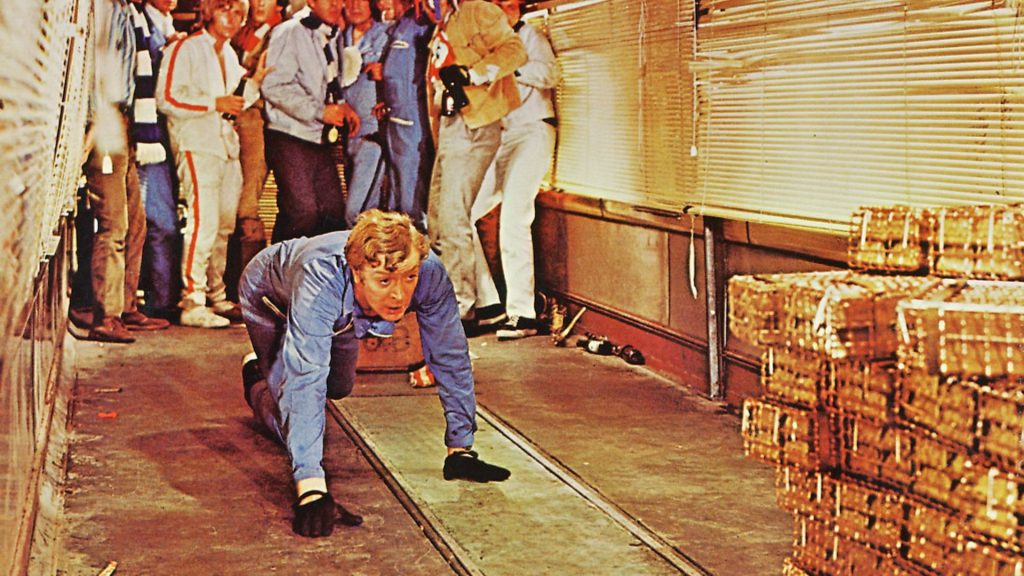

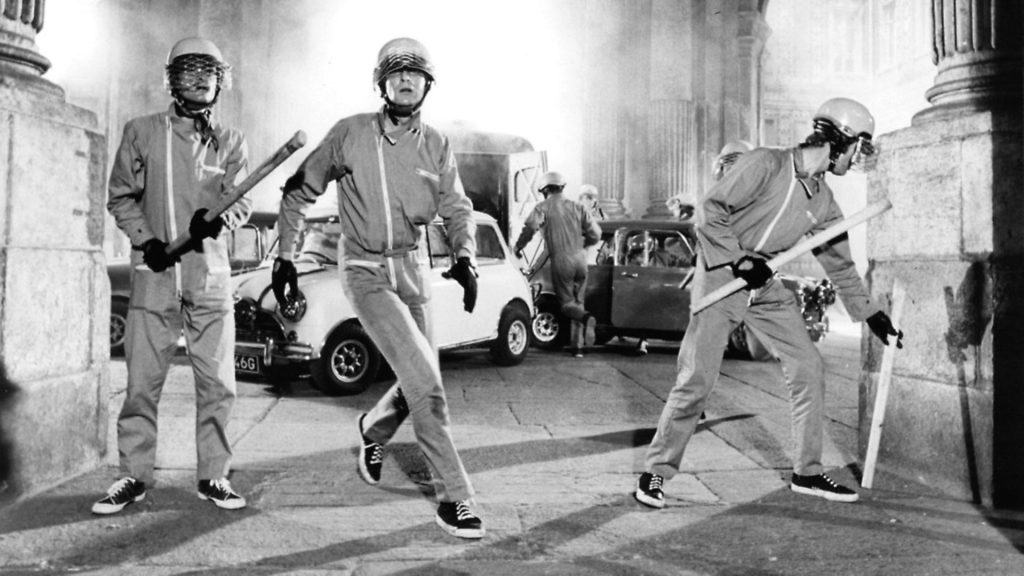

The new iteration saw Croker’s gang steal $4m worth of gold bullion from under the noses of both the Italian police and the Mafia, before creating a traffic gridlock and escaping the resulting chaos by driving through shopping centres and sewers.

From there they planned to head to the Alps and across the border to (neutral) Switzerland. However, hubris gets the better of them and their coach skids off the road and becomes perilously stuck on the cliff edge balanced between the weight of the gold at the rear and the robbers at the front. There they are left as the credits roll.

At the time, the bus wasn’t the only thing in the balance. As Troy Kennedy Martin was starting work on the new film script, British identity was in flux. That identity had long been defined in contrast to Europe. An imperial world view that often treated its continental neighbours with aloofness, even belligerence, was only reinforced by that empire’s solitary resistance to the Nazis in the early days of the Second World War.

By the late 1960s, the empire was dissolving into the Commonwealth and Britain’s economic and political status was on the wane. By contrast, the European Economic Community, a forerunner of the European Union, was on the up and as Britain made several, initially rejected, attempts to join, the country was starting to have to think of itself not on the edge but as part of Europe.

It was a change of mindset that would not come easily and one that is seemingly resisted in The Italian Job. The soundtrack speaks of “the Self Preservation Society” suggestive of a nation determined to remain independent, while the ship that takes the gang across the Channel is called The Free Enterprise. Most obviously, the getaway cars were iconically British Minis painted red, white and blue, which the film’s producer, Michael Deeley, said “obviously made a statement about ‘us’ and ‘them'”.

Some 30 years later, when lamenting that a 2003 remake was to be set in Los Angeles, Deeley went further, arguing: “It misses the entire point of the 1969 film, which was about us kicking European ass. It was the first Eurosceptic film.”

But that is not how it was originally conceived by Kennedy Martin when he was building on his younger brother’s idea. Heavily involved in left-wing politics, he saw the story as both a satire on Britain’s relationship with the Common Market and a hard-edged political and social commentary. “Europe was kind of in flames in 1968,” he would say later. “Revolution was happening everywhere, especially among young people like myself.”

That this more subversive side to The Italian Job has been long overlooked is down to Peter Collinson’s light-touch direction, which obscured the more biting satire of British chauvinism in the script, allowing the film to instead become a celebration of British superiority.

Thus, to fully understand The Italian Job the creative tension of Kennedy Martin’s and Collinson’s competing visions must be considered. It reflected the antagonism between the Europhile and Eurosceptic approaches to Britain’s relationship with the EEC in the years immediately before membership, antagonism that continued through to the 2016 referendum campaign and has only become more stark since.

And while Leavers, like Sarah Vine and her husband, might claim the film for their side of the argument, you don’t need to scratch too much below the surface to detect Kennedy Martin’s critique. Look beyond Collinson’s focus on capering and it becomes a somewhat different film. Mr Bridger, the criminal godfather played by Noël Coward who ultimately bankrolls the robbery, is a patriotic isolationist distrustful of Johnny Foreigner.

Strains of Rule Britannia! can be heard whenever he is on screen, his cell is decorated with photographs of the Queen and he expresses displeasure that some of the younger prisoners are not standing for the national anthem. Yet he spends the whole film behind bars. He is imprisoned, isolated from the outside world.

Croker, unlike Bridger, is not motivated by xenophobic patriotism. On the contrary he wants to break free of the rigid class-based strictures of British society any way he can. Indeed, when his appeal for backing is initially rebuffed by Bridger, Croker considers taking his plan to the Americans who, he says, “recognise young talent and give it a chance”.

The plan for the robbery is not Croker’s. Instead it is the brainchild of an Italian criminal, Roger Beckermann, who is murdered by the Mafia in the opening minutes. Croker has no qualms in fully embracing his European colleague’s plans.

Ultimately Croker exploits Bridger’s bluff xenophobic Euroscepticism to gain his support. He offers him the chance to take back control by imploring: “This is important; four million dollars, Europe, the Common Market, Italy, the Fiat car factory!”

Furthermore, the film’s production belies the notion of the independent ‘self preservation society’. Far from a wholly British endeavour, it was actually the result of a union of European talent.

The Minis were designed by Greek-born émigré Alec Issigonis and were driven by the Belgian stunt team L’Equipe Rémy Julienne. While the cars’ manufacturers, the British Motor Company, offered no support, backing from Turin-based Fiat was fulsome.

Kennedy Martin’s original ending had the gang making it to Switzerland only to find the Mafia waiting for them. However, Deeley conceived the cliffhanger to cut costs and facilitate a sequel which was ultimately never made.

In so doing, he had unwittingly created a denouement which is a perfect metaphor for the current state of the Brexit process.

As the camera pans away and the credit music kicks in, Croker and his gang are left teetering on a cliff edge with no Plan B and the gold tantalisingly beyond their grasp. If they get out of the vehicle and return to safety, they will lose their prize. However, the more they reach for it, the more likely they are to go tumbling with it into the abyss.