JASON SOLOMONS talks to the director of Radioactive, a powerful film not only about the pioneering scientist but her research that changed the world

Marie Curie is one of the most important women in European history. She was the first woman to win the Nobel Prize and still the only person to have won it in two different scientific categories, physics in 1903 and chemistry in 1911.

While working in Paris, she is most famous for discovering two elements, polonium (named after her native Poland) and radium, thus defining the phenomenon of (and term) radioactivity.

Her life and work are the subject of a new film, Radioactive, by Iranian French director Marjane Satrapi, best-known for award-winning animation Persepolis. In the film, Marie is superbly played by the English actress Rosamund Pike, while Sam Riley gets the less glamorous part of husband Pierre Curie. However, as one might expect with such an inventive visual director at the helm, Radioactive is not your normal, straightforward biopic.

Satrapi’s film is as much about the elements Marie discovers as it is about the woman herself, yet it’s also very much about a pioneering individual and the determination she had to exhibit to prove herself and her findings in the whiskery world of science.

‘I didn’t know the story at all,’ says Satrapi. ‘I thought I did but it turns out I only knew her name, you know, the Metro stop and the street and I remember how she was put in the Pantheon by [former French president François] Mitterrand but really these are the bare facts. Of course, what I didn’t know was the part of the story they want you to forget, the bit they don’t teach in schools – how she was demonised, the xenophobia against her, the demonstrations about her and her love life, even her contribution to saving lives in World War I.’

It’s clear from the start that Satrapi’s version of the Curie story will have magical and explosive properties, much like the director and her subject.

‘Yes, there was a spark between her and me, you could say,’ smiles Satrapi. ‘When I first read the script, I was on fire. I had to make the film.’

Initially, the filmmaker was reluctant to get involved with a story she felt had been told many times, a famous 1997 French film Les Palmes de M Schutz, starring Isabelle Huppert as Marie and based on a long-running play, being the key example. But the script this time was by the prolific Jack Thorne, he of projects as varied as This Is England, His Dark Materials and Harry Potter and the Cursed Child.

‘I found in it a very romantic and epic love story,’ fizzes Satrapi. ‘There were themes about the ethics of science and the thrill of discovery – it was so full of things, and that appealed to me as to how to bring it to life in my visual way.’

I wonder if there is connection with Marie Curie and the determined young girl punk growing up in Tehran in the last days of the Shah whom Satrapi turned into the subject of her iconoclastic 2007 animation Persepolis.

‘Well, I’m always for the oppressed one,’ she says. ‘I don’t like injustice, where and whoever it’s against, so I’m always on the side of that one. I would say I have an extreme sense of injustice, it drives me mad, so I was always going to tell a passionate story about Marie Curie. I think she felt injustice very deeply, too, that’s what I like about her.

‘So of course I am on her side, but it’s not a feminist film from that point of view. You know, when I talk about Marie to her granddaughter, Helene Joliot, she said my grandmother never was a feminist, it was all about not having enough money for research. She didn’t care about being a woman, she cared about being underfunded.

‘So yes, it’s about equality for men and women and that’s how things should be, but I don’t want to be the type of feminist who brings down men, or destroys anyone’s reputation. I am just standing up for Marie and her work.’

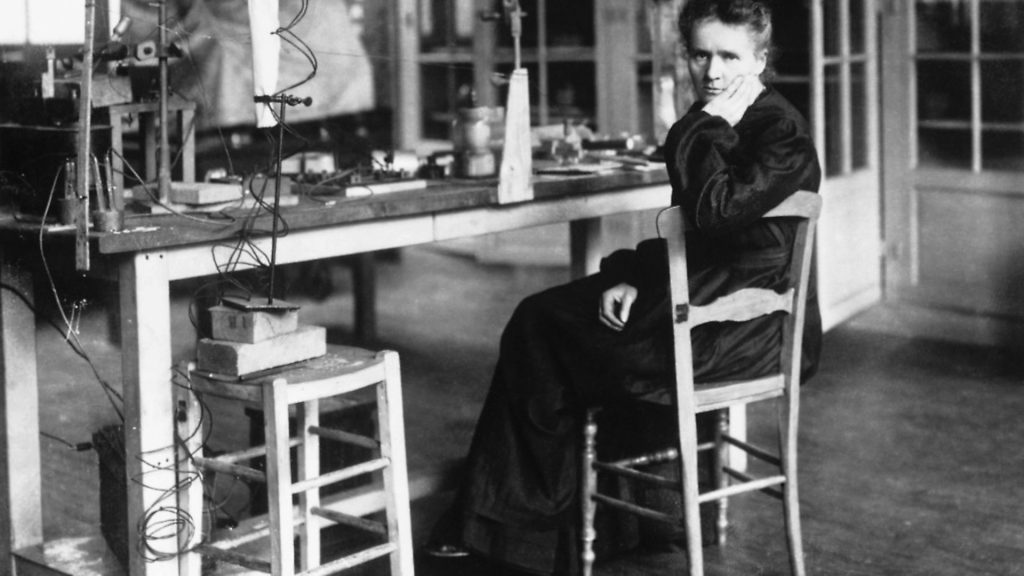

The film balances the biographical details and the scientific ones with a light touch. The ‘eureka’ sequences of the Curies ordering sacks of pitchblende – a radioactive uranium-rich mineral – and overseeing lots of bubbling away in their makeshift laboratory are real fun, much of it due to the, er, chemistry between co-stars Pike and Riley.

The latter, who starred as singer Ian Curtis in Joy Division biopic Control, says: ‘I knew my place in this film. Pierre was a generous man by all accounts and I knew my role here was to be more backseat – Marjane wanted to tell it from Marie’s perspective and from a feminist perspective and why not? I think Pierre was particularly good at supporting his wife and maybe for that time not all men were, but I think he admired her totally and was very much in love with her and I think he was much more romantic than her.’

Pierre and Marie married in July 1895 and went straight from the ceremony back to the lab, wearing the same outfits. They revealed their discoveries of polonium and uranium in 1898, and the film speeds up as they realise powerful uses their findings quickly become used for – from glow-in-the-dark effects in Paris dance halls, to matches, to a cure of baldness, a toothpaste or for the increasingly popular Parisian penchant for seances. You might even say there’s a tussle between seance and science.

Satrapi’s story-telling style is as inventive as its subject. She hops forward to tell the history of uranium in sketch-type flash-forwards: a child is given radium blasts to cure cancer, the atomic bomb is trialled in the Nevada desert, the nightmare of Chernobyl is briefly reconstructed.

‘It’s a biopic of radioactivity as much as it’s about Marie and Pierre,’ says Riley from the Berlin home he shares with his German actress wife Alexandra Maria Lara. ‘It’s about the moral consequence of what they discover and they’re both adamant that what they find remained open to all.

‘They didn’t take out a patent or anything, believing the elements they found were natural and therefore couldn’t be owned by anyone. But of course, that left their discovery open to exploitation, for good and for ill.’

For Satrapi, cramming in Curie’s achievements was the challenge. ‘I could have made a 40-hour film, the more I discovered about her and with what became of her inventions. But I had to have a point of view and idea and I had to follow it, from what I thought was one important moment to the next one.’

Curie in France remains widely known for her science – chemotherapy is still known as curietherapie. Curiously, Satrapi reminds me that they don’t have the chain of Marie Curie charity shops familiar on British high streets.

Of course, little of Curie’s Paris remains. The production was shot in Budapest, where Eiffel was a prolific architect and where Haussman designed the street layout. ‘It’s much easier to find the old Paris in Budapest than it is in Paris these days,’ remarks Satrapi.

Hers isn’t a rose-tinted view of that Parisan past, however. ‘No, because the past was terrible, always,’ she snaps. ‘It wasn’t better – if you were black, lesbian or gay, or a woman, you had s**t in your life. So I wanted to show a film about someone who shapes the future but cannot control it. It is about human nature – Marie unlocked an element of great power, she helped save lives with X-rays on the battle fields of World War One and she saw a cure for cancer. But 11 years after her death, you have the atom bomb – who’s fault is that? I wanted to think about that.’

Satrapi and I meet in the London offices of French-owned film company Studio Canal, who have recently moved to King’s Cross. Satrapi lives in Paris, not far from the Gare du Nord, so her back and forth to this spot has been regular, quick and easy. But we meet initially on December 31, as the winter evening closes in. Satrapi will be well out of London and back in Europe by the time Brexit formally happens. It’s a bitter irony for such a European production as Radioactive.

‘I tell you the past was bad,’ she continues firing. ‘We’ve had 75 years of no war. Now they want to go back to old ways. How stupid is that? Going back into the past is a terrible idea.

‘That’s what my film shows, even if the future can be frightening. Before this film, I was against nuclear energy but researching this, I learnt about the science of it and I think I’m converted to their view now. If it’s clean, I can listen to that.’

She veers off to talk about lithium batteries in electric cars, over-population, Game of Thrones and streaming platforms. You can see in her conversation the restless flitting and invention that appears on screen in her films. I always believe that directors reflect their films like a mirror. Satrapi doodles while she talks, neat, curves and straight line doodles, reminiscent of her graphic novel that become Persepolis. She even nibbles on a few plums in a bowl on the desk – she followed Persepolis with a movie called Chicken with Plums (Poulet aux prunes).

I hope she’s not going radioactive for this new film. Pointing out these details, I surprise Satrapi, as much as it’s possible to surprise this woman often described as a ‘force of nature’. I think that’s a rather disparaging phrase. So does she.

‘Ha! That’s what they called Marie Curie, too,’ she laughs. ‘So maybe we have an electric connection, me and her. Maybe it’s something spiritual. You know, I show in my film, that science was very interested in the electricity of the spiritual world and Pierre believed if you could unleash such power from an element in nature, that there must be something in the air.

‘It’s why I have electronic music in my film [the highly effective score is by Russian-born composer brothers Evgueni and Sacha Galperine], to capture the age of invention which all came so quick around Marie’s time – street lights, gramophones, cars, X-rays, telephone, plane, bombs…’

For all the romance of the era she puts on the screen – and before she takes the high-speed train to escape the curtain falling on Brexit Britain – I make sure once more that she wouldn’t want to return to that age. ‘Oh no, I like my washing machine too much,’ she explains. ‘I’m obsessed with doing my laundry and I love flying, travelling, getting away quickly. Plus, like Marie Curie, I hate long dresses and corsets.’

Radioactive is due to be released on March 20