From his treatment of dancers to his testimony during the McCarthyite witch-hunt, choreographer Jerome Robbins still has much to answer for, Yet there is also still much to celebrate.

Centenaries for artistes and composers are like parties to which all are invited. Yet the American choreographer Jerome Robbins, whose hundredth birthday falls on October 11, was so personally loathed that some of his colleagues joked during his lifetime that he was unwelcome at any festivities.

In her one-woman show, the comedienne Beatrice Arthur recounted how one dancer had trained his Yorkshire terrier accordingly: At cast parties, the door to the flat was left open and ‘at some point in the evening, [the dancer] would go to the doorway and look out and say, ‘Oh my God, here comes Jerry Robbins!’ And the little dog would fling himself against the door and slam it shut.’

Admitting that Robbins had substantial talent, Arthur, who performed in Fiddler in the Roof under his direction, added: ‘Actually, he was the only director who ever made me cry. He was a really dreadful human being. Everybody hated him.’ With such a guest, how to plan a centennial knees up?

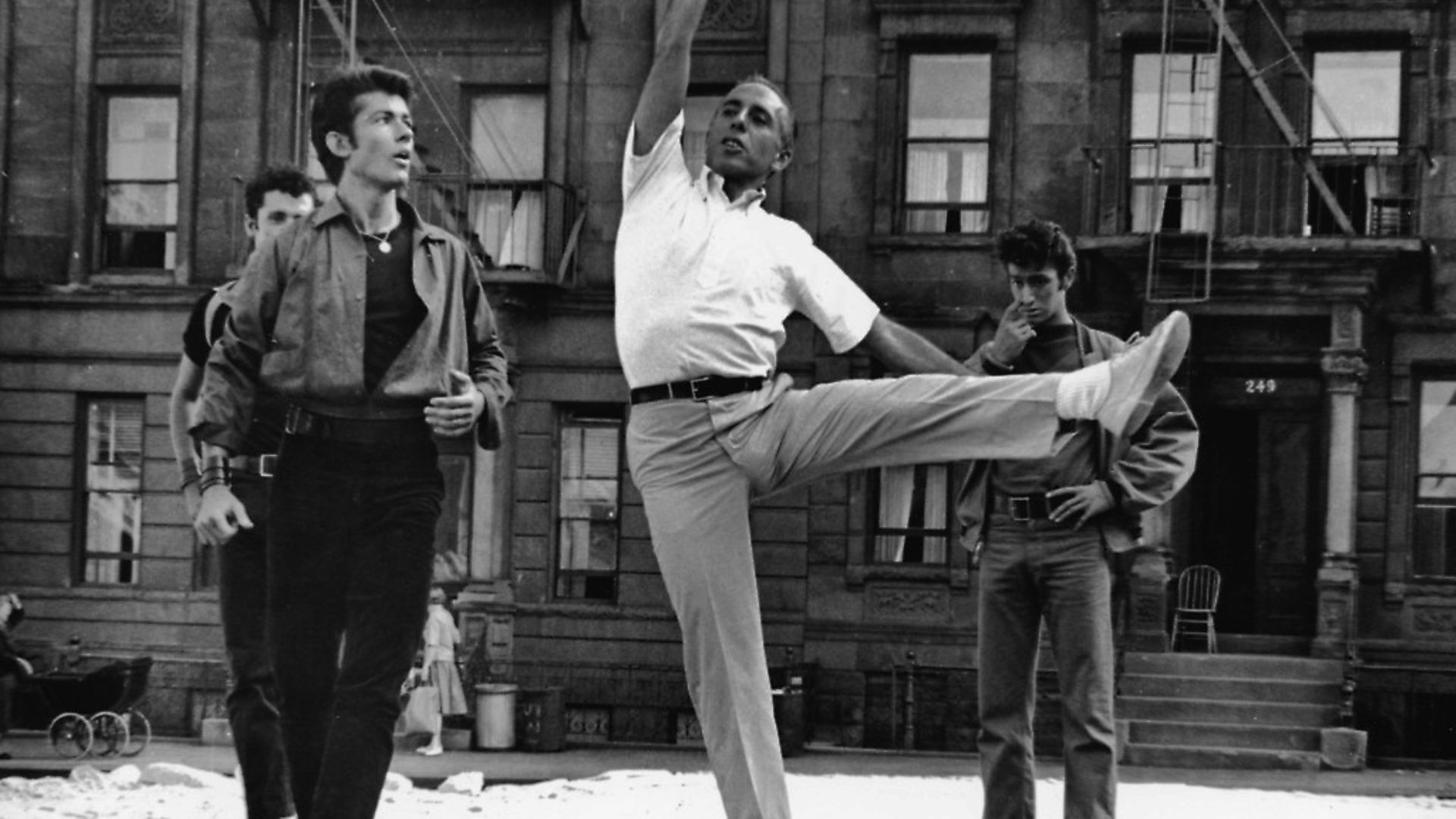

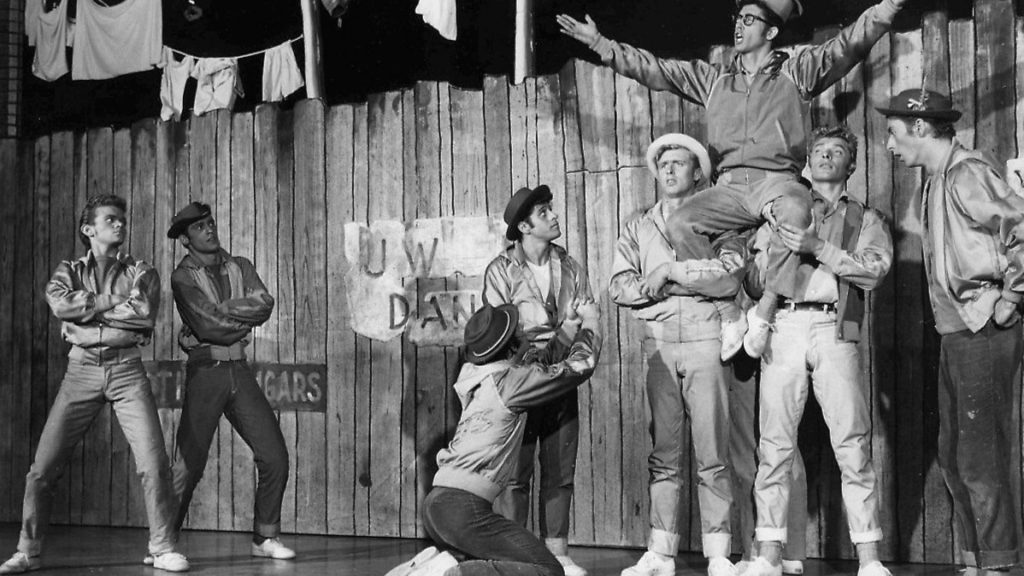

Surely some commemoration is due Robbins, who choreographed and directed the iconic American musical comedies On the Town, Peter Pan, The King And I, The Pajama Game, Bells Are Ringing, West Side Story, and Gypsy, among others. His dances conceived for Broadway were forceful, zesty, imaginative, forever young. Robbins, who died 20 years ago, also delved into classical ballet, notably with Glass Pieces (1983), Afternoon of a Faun (1953), and Antique Epigraphs (1984). He also collaborated with George Balanchine at the New York City Ballet on such projects as Firebird (1970) and Pulcinella (1972). Robbins’ formal ballets were often forced and artificial, as if expressing his status as an inferior American version of Balanchine.

Yet Robbins may be most respected today as a ballet choreographer. International performances and mini-festivals have occurred this anniversary year, with Robbins’ slapstick The Concert (or The Perils of Everybody) (1956) scheduled for December 18 at London’s Royal Ballet. Jerome Robbins: A Life in Dance by Wendy Lesser, heavily focused on classical dance, has just appeared from Yale University Press.

But in the transitory world of musical comedy, Robbins’ legacy is evaporating alarmingly. An early warning sign occurred in 2016, when a Broadway revival of Fiddler on the Roof hired Hofesh Shechter, an Israeli-born, UK-based choreographer, to ‘update’ Robbins’ dances. Such legendary moments as the so-called Bottle Dance, in which top-hatted wedding guests balance wine bottles on their noggins, was retained. It had become, with time, a quintessential image of Robbins’ most legendary creative achievement. Even earlier, in 2015, a revival of The King and I, currently staged in London, gave carte blanche to the choreographer Christopher Gattelli to alter Robbins’ original dances.

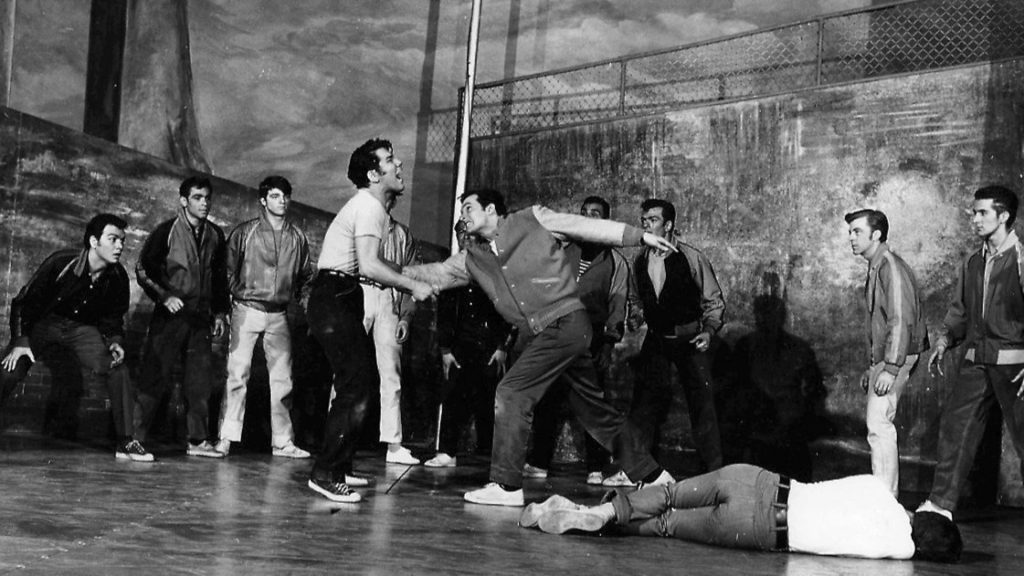

In July, further news arrived that Robbins’ second most acclaimed innovation, the dances for West Side Story, would be obliterated entirely in a new production directed by the Belgian Ivo van Hove. The van Hove version, to open on Broadway in December 2019, will instead feature choreography by van Hove’s compatriot Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. This wholesale eradication of Robbins’ work has gone unexplained, apart from van Hove’s mild claim of wanting to present a ‘new reading’ of the show.

Even the severest critic of Robbins as a choreographer might wonder at these new developments. Most agree that he was hell to work with on a personal level, but the results on the Broadway stage were brilliant. In classical dance, part of the challenge was Robbins’ indecisiveness.

Preparing a ballet, he might develop four versions of each sequence of steps, and dancers were expected to remember each version in the proper order for rehearsals stretching over a year or more, or risk his wrath.

The biographers Deborah Jowitt, Amanda Vaill, and Greg Lawrence have implied that Robbins would erupt into rage because of his insecurity in the lofty domain of ballet. Enabled by years of psychoanalytic treatment, Robbins became skilled at diagnosing personal weaknesses of performers. In Lawrence’s Dance with Demons: The Life of Jerome Robbins (Putnam, 2001), Tony Mordente, who was in the Broadway and West End casts of West Side Story, explained that when Robbins was in a choleric mood, he ‘not only attacked you, he attacked your family, your background, where you lived, how you lived, who you studied with’.

Robbins abominated his own origins and identity. Born Jerome Rabinowitz to a Jewish family and raised in Weehawken, New Jersey, he was convinced that being Jewish, gay, and from New Jersey was a cursed identity that he must always publicly flee. The critic John Gruen alleged in a 2008 memoir that Robbins’ ballets contained the ‘seeds of fear – fear on the part of the dancers still in the throes of Robbins’s deliberate cruelty and seething fury’.

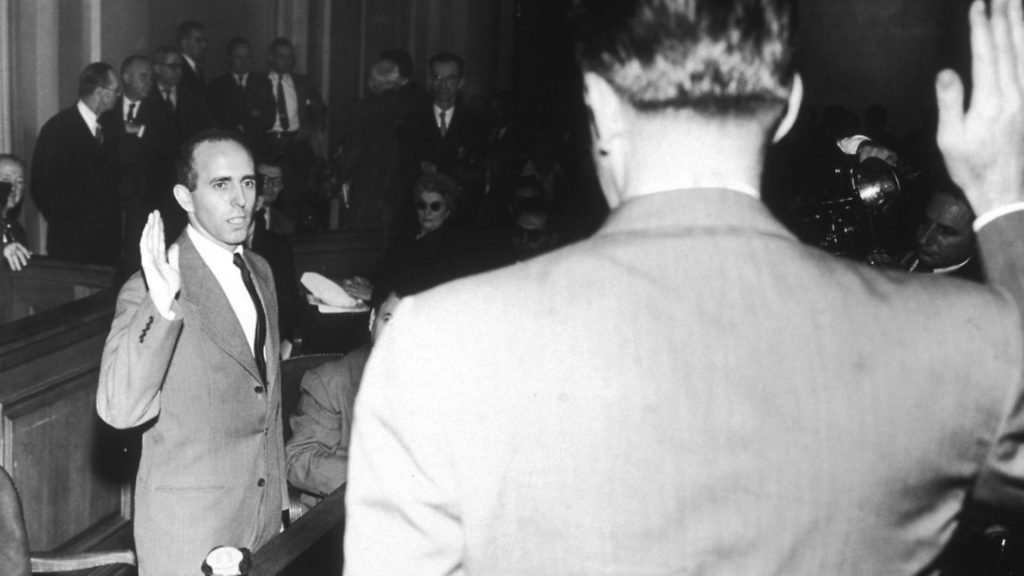

Beyond personal insults to underlings, Robbins was notorious for his testimony in 1953 as a former member of the Communist Party before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Ostensibly to ensure that his career would never be impeded, he appeared before an investigative group of the United States House of Representatives and named acquaintances as fellow communists. Among the supposedly dangerous radicals he informed upon were second-string actors who promptly became unemployable for years in the witch hunt atmosphere of the time.

Arthur Laurents, a colleague of Robbins on several projects, epitomised his former friend in a play, Jolson Sings Again (1995): ‘You’re not evil because you informed; you informed because you’re evil.’

Laurents diagnosed Robbins’ willingness to damage unoffending bystanders as proof of a lack of humanity. This flaw motivated the way Robbins treated colleagues throughout his career. Like Shakespeare’s Iago, Robbins never convincingly explained his malignity, although he floated some excuses. Decades later, he privately ventured that he had feared being outed as a homosexual. Yet in truth, public knowledge of his sexuality would hardly have impeded his career as a choreographer on Broadway or in the ballet world.

A more plausible explanation was offered by Bob Currie, stage manager for Fiddler on the Roof, as cited in Dance with Demons. At the opening-night cast party for Fiddler, Robbins told Currie that for the first time he saw the performers as human beings. Before then, ‘he’d thought of them only as obstacles in the way of his work’. Seeing other human lives as impediments characterised Robbins’ professional approach. Privately, he was capable of kindness, generosity, and other such virtues.

Yet onstage, unlike Balanchine’s glorification of the female dancer, Robbins’ quintessential expression of womanhood is The Cage (1951), which has been described as depicting the ‘feral instinct compelling the female of an insect species to consider its male counterpart as prey’.

This insectification of human relations aside, what remains of Robbins’ ballets? Balanchine, an accomplished pianist, knew precisely which musical scores begged to be complemented by dancing and which did not. Robbins chose to add steps to Bach’s Goldberg Variations, an entirely self-sufficient work, if ever there was one. Robbins then imposed impossibly slow tempos upon the pianist to fit the movements of his dancers, thereby deforming the musical score. The results were graceful, stately, and dignified, and won critical praise. Yet Robbins’ Goldberg Variations could not compare with Balanchine’s profound understanding of the piano, dance, and emotional interactions, in Robert Schumann’s Davidsbündlertänze (1980), for example. In August 2004, the dancer and writer Toni Bentley wrote in the New York Times: ‘Robbins was Salieri to Balanchine’s Mozart, and we all knew it.’

Rather than trying to rival Balanchine’s profundity of understanding of the classical and Romantic traditions, Robbins was better suited to modern idioms. His Glass Pieces (1983), to music by Philip Glass, energetically broke the tedium of the American composer’s minimalist monotony. Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun (1953) to Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune by Debussy, is a fresh, ironic rethinking of a ballet about a faun meeting nymphs, originally choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky in 1912. Robbins’ mordant update is set in a ballet studio, with male and female dancers capturing the narcissism and self-obsession required by the art form.

Another Robbins ballet inspired by Debussy’s music, Antique Epigraphs (1984) was a further high point, with ballerinas assuming positions echoing the angularity of dancers represented by Edgar Degas. Critics who complain about the artificiality in these dances overlook that classical ballet in the mid-to-late 20th century was necessarily a self-aware, self-referential art. By contrast, Robbins’ choreography to Chopin’s piano music in Dances at a Gathering (1969) and In the Night (1970), although praised at the time, amounted to watered-down Balanchine, with dancers posing as if in a mystifying mating ritual.

Unequivocal admirers of Robbins who praise these and other dances tend to justify even his cruellest rehearsal methods. They rationalise that he was just as critical of himself as he was of the performers who worked with him. This rather misses the point. Other modern choreographers, including Anthony Tudor and Martha Graham, were reputedly difficult to work with. Robbins was always seen as a more fanatical, frenzied case.

That vehement precedent might be one reason why the Jerome Robbins Foundation, which controls the rights to his works, has opted for an alternative approach, amenably accepting alterations or even supercessions of his work. His posterity looks likely to include further annihilations of the van Hove/ De Keersmaeker ilk.