Post-virus politics might look very different, says John Kampfner, and there are signs that the centrists are fighting back

The leader of the free world dismisses it as a hoax. Then he blames it on foreigners. Then he declares a national emergency ‘two very big words’. Then he tries to bribe the Germans to give him exclusive access to antibody research. Over the past four years the world has got used to the dangerous buffoonery of Donald Trump. Will coronavirus bring to an end this ugly era of populists and rehabilitate the less colourful but more thoughtful type technocrat?

The Americans have that choice shortly before them with the presidential election in November, assuming everything takes place on schedule. Until the outbreak of the current emergency it had become axiomatic to assume that voters would continue to embrace irrational emotion over common sense and give Trump a second term.He talked a good talk – if brash nationalism is your thing. The stock market was high. Jobs were in plentiful supply, even if many were in the gig economy. America First was making his base, and just enough floating voters, feel better about themselves.

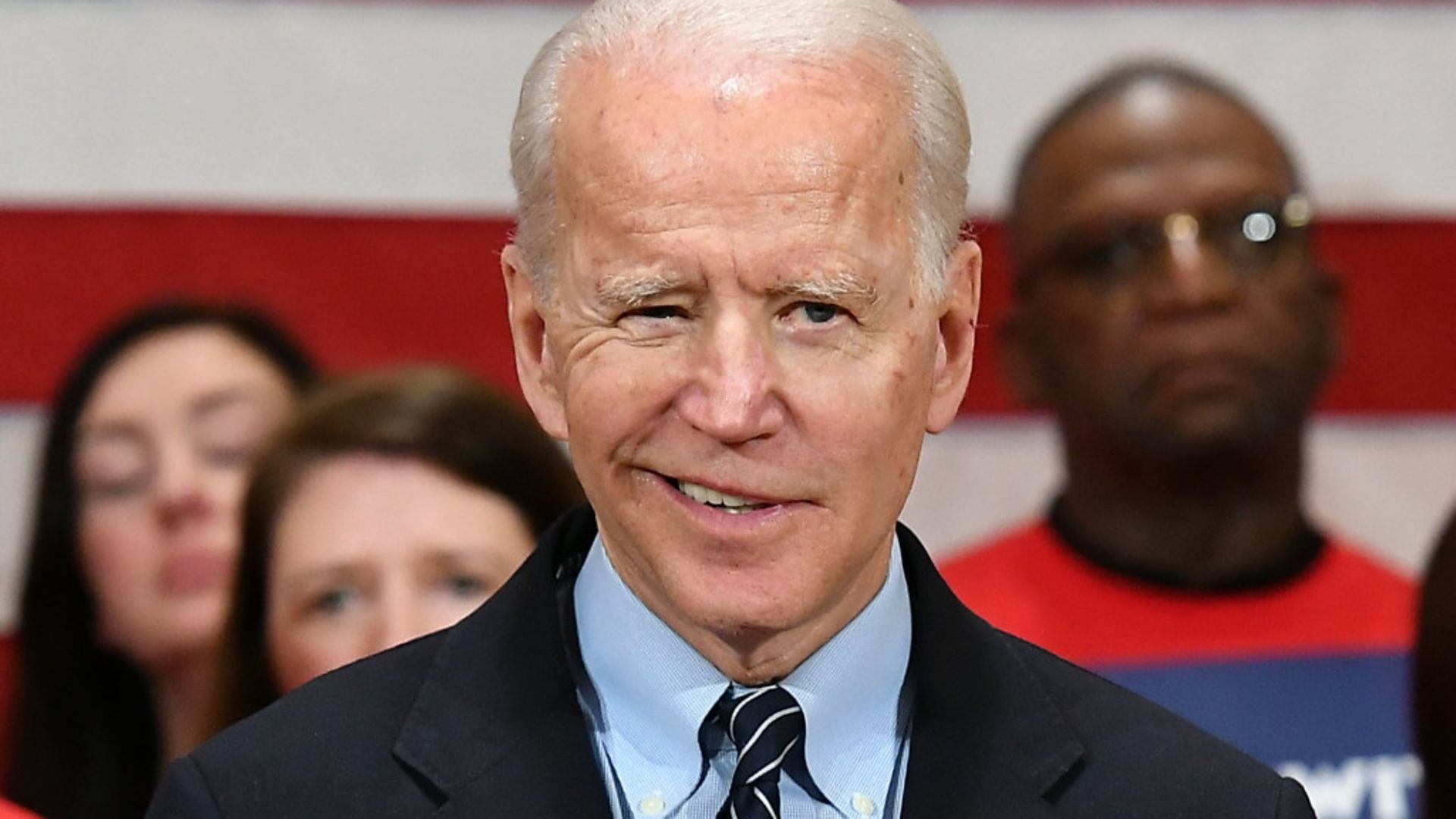

Meantime, the Democrats were tearing strips off each other. None of the candidates was cutting through until the choice was whittled down to two septuagenarian men (three if you add Trump) – the radical socialist in Bernie Sanders and the centrist Joe Biden.

With enough swing states coalescing around Biden in the primaries, the assumption was that he would win the nomination – and then would stumble to a debilitating defeat.

Wherever you looked around the world there appeared to be little counter-narrative to the autocrat or his (and they are all male) nationalist-populist friend in the West.

Viktor Orban was doing nicely in Hungary. The Law and Justice party was enjoying continued power in Poland. Jair Bolsonaro was doing fine in Brazil… we all know the list.

At the same time, the few beacons of reason – Jacinda Arden in New Zealand, Justin Trudeau in Canada and Germany’s Angela Merkel – were stumbling from one crisis to another.

And what of the UK? Last December’s general election gave voters an unenviable choice between two hapless figures.

Boris Johnson’s victory was far less a vote of faith than a vote with gritted teeth.

But win he did, resoundingly, suggesting that the party-that-loves-to-lose, Labour, was in for another 10 years in the wilderness.

With Johnson’s handling of coronavirus coming under intense scrutiny, and with polls predicting that Keir Starmer will be voted in as leader of the opposition, could Johnson’s foppish manner be misplaced?

Are character and solidity set for a return? When the pandemic eventually ends – and nobody can predict how deeply or how long it will affect each nation – will priorities have changed?

Johnson is trying already to make that transition to statesmanship rather than joker, reinforced by surrounding himself with two experts in the chief medical officer and chief scientific officer.

But any discerning observer knows that he doesn’t look the part or sound the part.

In the US, the mismatch is considerably starker. Of all the people you might want to guide you through a crisis such as this, the loud-mouthed Trump would not feature highly on your list.

The White House has felt no need to pull together other countries for a coordinated global response.

Nowhere was that more obvious than in Trump’s out-of-the-blue announcement banning all travellers from the Schengen Area – except the plucky Brits – before adding the UK a few days later.

As Gordon Brown wrote recently, contrasting the present situation with the coordinated response from global leaders during the 2008 financial crash: ‘This us-versus-them nationalism has spawned a blame culture, with under-pressure governments holding everyone but themselves responsible for anything that goes wrong. And yet an ideology of ‘everyone for himself’ will not work when the health of each of us depends so unavoidably on the health of all of us.’

Biden’s responses to the pandemic have deliberately highlighted a difference in tone. His message to voters has been that he is the man with experience; he may not be the most charismatic person in the world, he may stumble a bit, as he is getting on.

But he can lead America back into normality – post-virus and post-Trump.

Biden would – as virtually all US presidents, Republican or Democrat, have done – work closely with other countries.

A traditionalist on foreign policy, as on much else, he believes that close friendships with Europe and elsewhere are vital for US security.

If, as I suspect they will, voters will, post-virus, want less of the macho and more of the reasoned, then Biden and Starmer will get a better reception.

The one lesson they, and others like them, will have to learn from the populists is to be more tenacious.

Tony Blair’s government in 1997 had such a majority it could have been truly transformative. It did, of course, make some changes, but they were a fraction of what could have been achieved.

Barack Obama made some progress in his first two years, but not nearly enough. Then he was effectively blocked when the Republicans took back Congress and blockaded major legislation.

In other words, more centrist governments should abandon caution. On paper, even though not as revolutionary as Bernie Sanders or Jeremy Corbyn promised to be (Labour’s 2019 election manifesto was an extraordinary wish-list), Biden and Starmer are promising radical reform.

Biden is promising $750 billion to accelerate Obama’s health care changes, a staggering $17 trillion in clean energy investment and tighter regulation to bring emissions to zero by 2050; a combined $2 trillion in new spending on early education, post-secondary education and housing, a $1.3 trillion infrastructure plan, and a $15 minimum wage.

To pay for it, to raise $4 trillion over a decade, he would increase taxes on the rich, making it – if enacted – one of the largest wealth transfers in American history. Yet even then, the 1% richest would see their annual income drop by only 10-15%. As for gun control, he promises stricter measures – but that always seems to be the toughest nut to crack in US politics.

Starmer’s 10 pledges have been criticised by some as a variant of Corbyn’s list. He has recommitted Labour to public ownership of rail, mail, energy and water, outlined plans to abolish universal credit, pledged the abolition of tuition fees and promised to introduce the party’s Green New Deal.

He would raise revenue in part by increasing income tax for people earning over £80,000, alongside reversing cuts in corporation tax and clamping down on tax avoidance (something all governments promise but seldom follow through).

In among all the uncertainty with Covid-19, some broad predictions do not seem misplaced. Health systems will not have to fight as hard as they have done for better funding.

The role of the state will not be so disparaged as it has been during the three-decade hegemony of the ultra-free marketeers.

Alongside that, will society really become more community spirited and less selfish?

Perhaps it will, but only in part. What it will prize is no-nonsense reliability. It is time for the technocrats to show their colours, radical but rational. The message from voters will be: don’t hold back.

Defy your detractors and show more courage than the likes of Blair and Obama did.