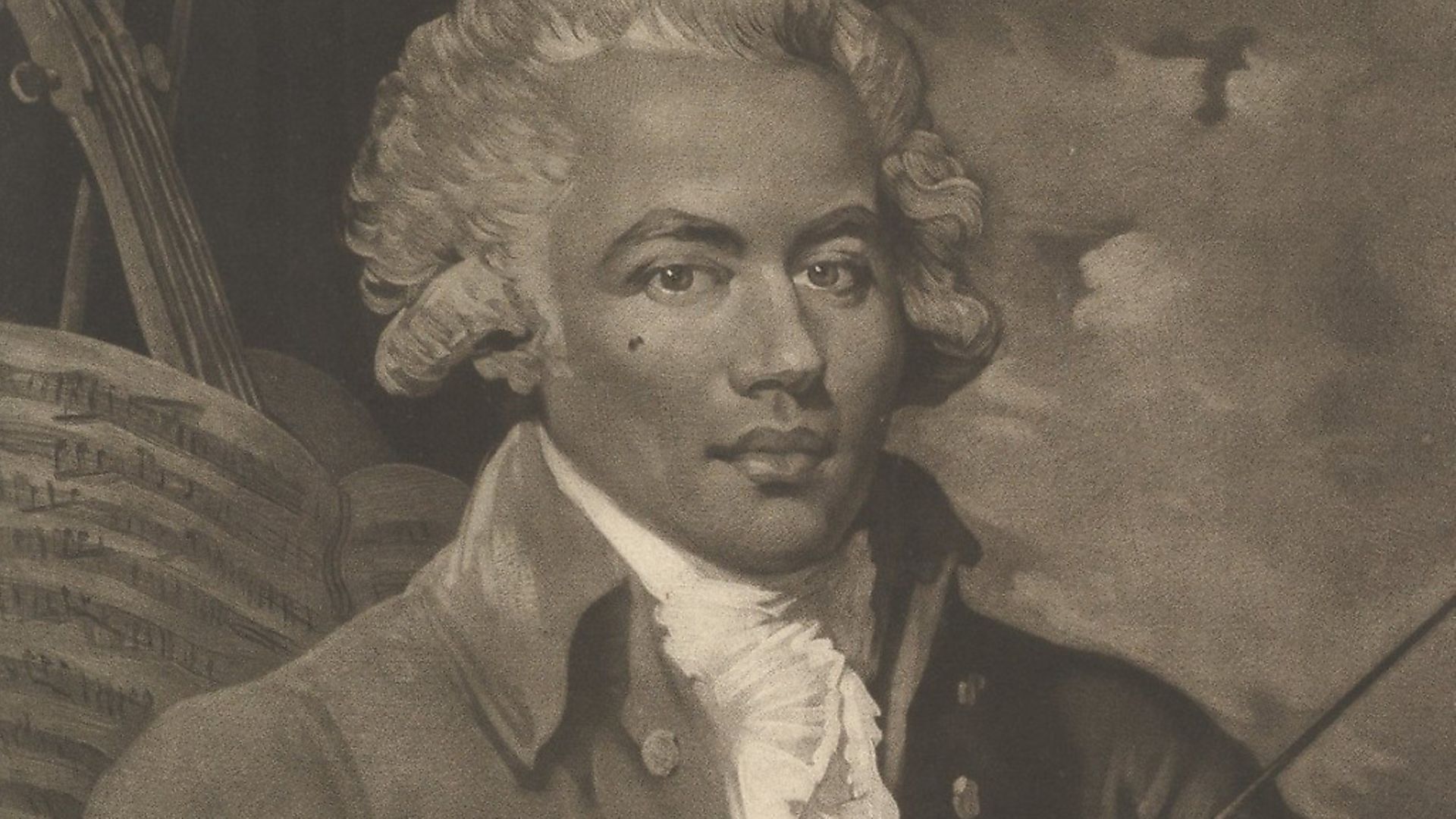

CHARLIE CONNELLY profiles the fencer, violinist and revolutionary commanded of the French Garde Nationale.

On April 9, 1787, at the behest of the Prince of Wales, an unusual fencing match took place in London between Mademoiselle d’Eon, a French former diplomat and spy who lived as a woman for decades, and Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-George, one of Europe’s finest fencers of the age.

‘The novelty of a lady in petticoats engaging the most able and experienced master of the noble science of defence excited universal pleasantry,’ wrote a spectator afterwards. ‘Even such as had formerly known her en culottes were not a little surprised at the skill she showed at fencing with Mr Saint-George.’

Strange as it sounds, the Mademoiselle, who had variously fought as a soldier during the Seven Years War and lived in Empress Elizabeth of Russia’s court as a woman, was the least remarkable of the two combatants. Her opponent was a man who lived an extraordinary life in extraordinary circumstances.

Joseph Bologne wrote three string quartets, two symphonies, six comic operas, three violin sonatas and 14 violin concertos that are still performed more than 200 years after his death. He was one of the finest violinists of an era that produced more than its fair share of virtuosi, was regarded as the best fencer in Europe and was a leading light of the campaign to abolish slavery in Britain and France. He performed for and with European royalty and drew considerable crowds to the concert halls and fencing pistes of the continent’s highest capitals of culture. John Adams, the president of the United States, described Bologne as ‘the most accomplished man in Europe’, yet there’s still a strong chance you’ve never heard of him.

The reason why can possibly be found in an item that appeared in British newspapers during December 1786 that noted how Saint-George was ‘superior at the sword’ and praised his peerless abilities as a dancer.

‘He plays seven instruments beyond any individual in the world,’ it gushed, ‘and speaks 26 languages, maintaining public theses in each.’

Then came the pay-off.

‘He walks around the various sciences like the master of each,’ it read, ‘and, strange to be mentioned to white men, this Mr St George is a mulatto, the son of an African mother.’

To this day Joseph Bologne is more often than not referred to as the ‘Black Mozart’ when by rights his achievements deserve neither qualification nor comparison. He lived through some of Europe’s most tumultuous times, often finding himself at the heart of them, and overcame a number of obstacles to succeed in a variety of fields. If the polymath traditionally struggles to achieve the respect they deserve, a black polymath in late 18th century Europe had to struggle more than most. He would always remain an outsider.

Bologne was born on Christmas Day, 1745, at Basse-Terre on the island of Guadeloupe in the Caribbean Sea. His father was George de Bologne Saint-Georges, a 34-year-old slaver and plantation owner, and his mother Ann, a 16-year-old slave in the service of George’s wife.

Unusually for a time when slaves of African descent were regarded by their owners as savages, George was not only willing to acknowledge his paternal responsibility but act upon it too. When Joseph was seven years old his father took him to France and placed him in a boarding school, returning two years later with Ann and installing mother and son in an apartment in the Saint-Germain district of Paris.

Bologne showed early promise as a violinist, harpsichordist and particularly as a fencer, entering the elite fencing academy of Nicolas Texier de La Böessière at 13 and emerging six years later as a swordsman so accomplished, he became a member of the king’s guard with the title Chevalier de Saint-Georges. Agile, intelligent and skilful, he was the most highly sought-after name at fencing events on both sides of the English Channel, rarely allowing opponents to even score a hit let alone win a match.

Yet it would be as a musician and composer that Bologne would make his name. By 1769 he had become such an accomplished violinist with the Parisian orchestra Le Concert des Amateurs that he was elevated to concert master. Three years later he became a soloist and in 1773 Bologne was appointed director of the orchestra. The influential L’Almanach Musical wrote in 1775 that the orchestra under Bologne’s direction was ‘the best orchestra for symphonies in Paris and perhaps in Europe’.

His own brilliance as a performer was such that leading contemporary composers wrote violin concertos specifically for him and he filled concert halls and salons wherever he went, often performing his own compositions. Before long he was tutoring, performing for and performing with Marie Antoinette at the palace in Versailles.

It wasn’t all plain sailing, however. On a visit to England he was confronted in the street by a man armed with a pistol demanding his valuables. When Bologne disarmed the man, according to one report ‘four more rogues hidden until then attacked him and he put them all out of commission. M. de Saint Georges received only some contusions which did not keep him from going on that night to play music in the company of friends’. It’s probable that this was an assassination attempt at the behest of supporters of the slave trade.

Bologne had been criss-crossing the Channel regularly at that time, partly to perform concerts and recitals but mostly to lend his support to the increasingly powerful anti-slavery lobby in England. He met regularly with abolitionists like William Wilberforce and John Wilkes and assisted in translating British abolitionist pamphlets into French for the Société des amis des Noirs, the Society of Friends of Black People, that he’d helped to establish in France.

When revolution broke out in 1789 Bologne, despite his aristocratic connections, immediately sided with the revolutionaries. In the manifesto of the revolution he saw a perfect opportunity to end both the French slave trade and the inequalities and injustices experienced by black people in France. For all that he’d raised himself to the highest echelons of French society there were always barriers and humiliations. As a black man he was barred from inheriting his father’s titles and forbidden to marry a woman from the higher classes.

When the revolution broke out, Bologne became one of the first to volunteer for the new Garde Nationale. By 1792 he was a colonel in command of the 1,000-strong Légion franche de cavalerie des Américains et du Midi, the first regiment of any European army to be made up entirely of black soldiers (including the swashbuckling Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, father of Three Musketeers novelist Alexandre Dumas).

So successful a leader was Bologne that before long the unit became known simply as the Légion St-Georges. But despite leading his troops with distinction, Bologne’s extracurricular musical activities – he even formed a small orchestra of military men – contributed to accusations that he was not giving the revolution his full attention. In November 1793 he was arrested under the new French Law of Suspects and imprisoned without charge as part of the Great Terror until after almost a year the Committee of Public Safety found that Bologne had been removed from his command without cause. He was released from prison but would never regain his command.

While it must have come as some consolation that while he was in prison the National Convention abolished slavery in the French colonies, for all his achievements, for all his brilliance in music, fencing and as a military leader, Joseph Bologne was tainted by prejudice throughout his life. Tropes still familiar today were whispered and sometimes expressed openly, such as this snippet from the Times in September 1789 referring to his conduct on the fencing piste.

‘Mr St George acquired his ‘war whoop’ in excursions against the Cherubee Indians,’ it said inaccurately of his occasional exuberant yelps during fencing. ‘It may be a very proper accompaniment for a tomahawk or scalping knife, but it surely is very unbecoming in the elegant exercise of the sword.’

Never mind he composed some of the most exquisite violin concertos ever written. To the ignorant, he would always be a savage.