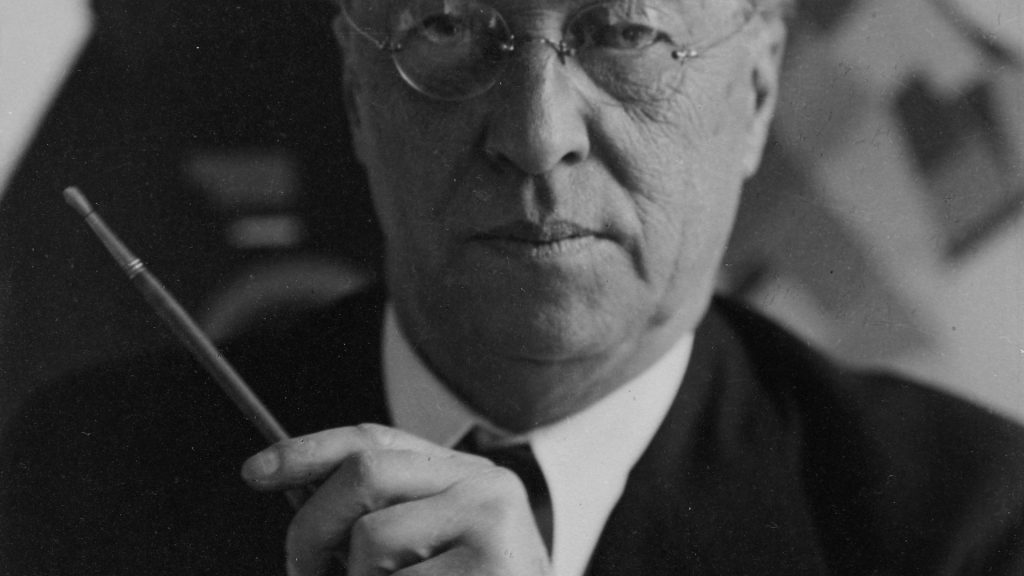

Colour was always at the core of Wassily Kandinsky’s art. Claudia Pritchard reports on a stunning exhibition which traces his creative journey as he was shifted around Europe by the events of the early 20th century

The career path from lawyer to artist is not often taken. Tchaikovsky managed to duck out of jurisprudence and into composition. But for his fellow Russian, Wassily Kandinsky, the circuitous route itself helped forge his distinctive painting style.

Born in Moscow in 1866, Kandinsky read law and economics in the city, and took an especial interest in the legal systems of rural communities. As an expert in this field he was asked to join an ethnographic survey of Vologda in the north, in 1889.

There he was captivated by the brilliance of traditional art, with its fearless reds and optimistic yellows.

These dramatic colours and the unashamed shifts from one side of the colour spectrum to the other were to become essential to his own artworks.

At 30 Kandinsky abandoned his legal career altogether and set up as a painter. Moving to the vibrant centre of the European art scene in Munich, his personal style quickly developed as he challenged accepted norms one by one.

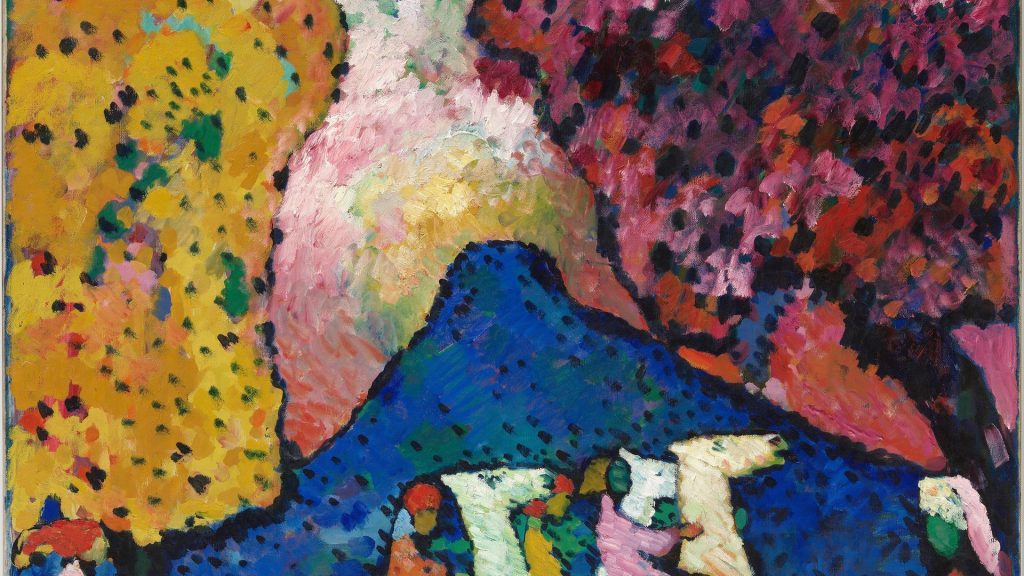

Observational scenes flattened and gave way to less representational forms. Colour no longer replicated real life, but showed instead the artist’s reaction to what he beheld, so that by 1908 and The Blue Mountain, not only is the hillside azure, but horses are yellow and human faces green.

Apart from the pivotal ethnographical tour, two other formative influences on Kandinsky echoed throughout his career. One was discovering on a gallery visit before leaving Moscow the Haystack pictures of Claude Monet.

This series, depicting the same mounds of hay at different times of day, amazed Kandinsky: here the stacks were red, here purple, then silvery grey. At the same time as these infinite possibilities for colour opened up, he heard the opera Lohengrin by Richard Wagner, with its vivid orchestral effects.

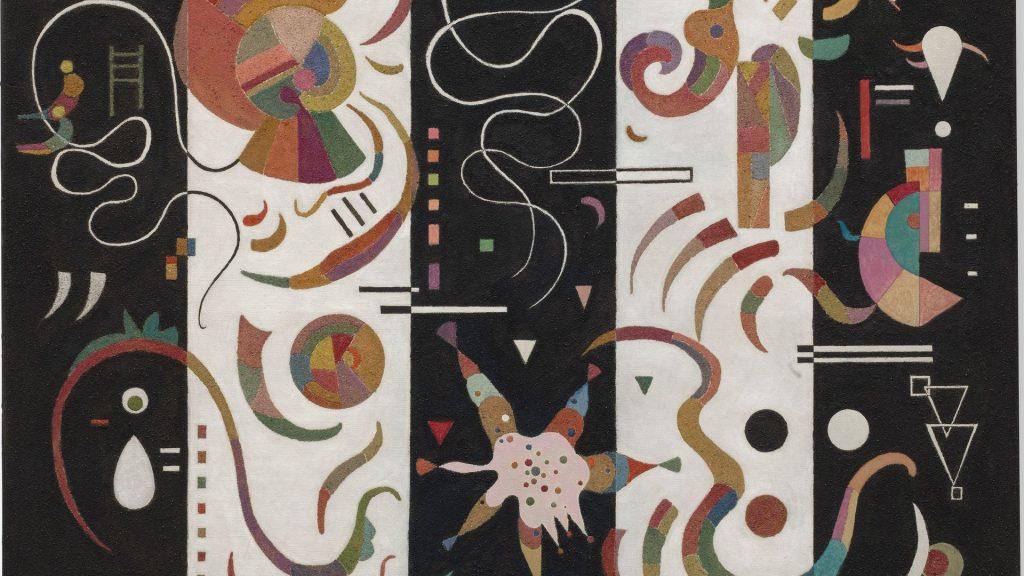

So began a lifelong endeavour to do on canvas what a composer does with sound – to create a world that is not figurative but yet coherent and that, without direct reference to any event or person, arouses emotions in the listener/viewer.

Kandinsky had synaesthesia, the condition that links sound to colour. In artists and composers such as Olivier Messiaen, who also had the condition, this crossover between the visual and the aural is like an extra sense.

The Russian went so far as to name his works, with reference to the musical world, Improvisations and those that he – and the world – considered his masterpieces, Compositions. There were 10 Compositions, of which three were lost.

It was a visit to Kandinsky in Munich by the American collector Solomon Guggenheim in the 1930, who had been buying his work since 1922, that was ultimately to bring Kandinsky to a wider public.

In 1939 Guggenheim opened New York’s Museum of Non-Objective Painting, forerunner of the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum. Today, the great Guggenheim collection, further enhanced by the gifts of other benefactors, includes some 150 works by Kandinsky.

Since October 1997, when the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao opened in Frank Gehry’s spectacular building, works have been loaned to by New York, most recently for a large-scale exhibition entitled simply Kandinsky, which can be viewed online.

Here the artist’s journey from figurative to abstract painter is traced in 62 works showing the influence of his travels not only through his native Russia and adopted home of Germany but also France, and the impact of two world wars.

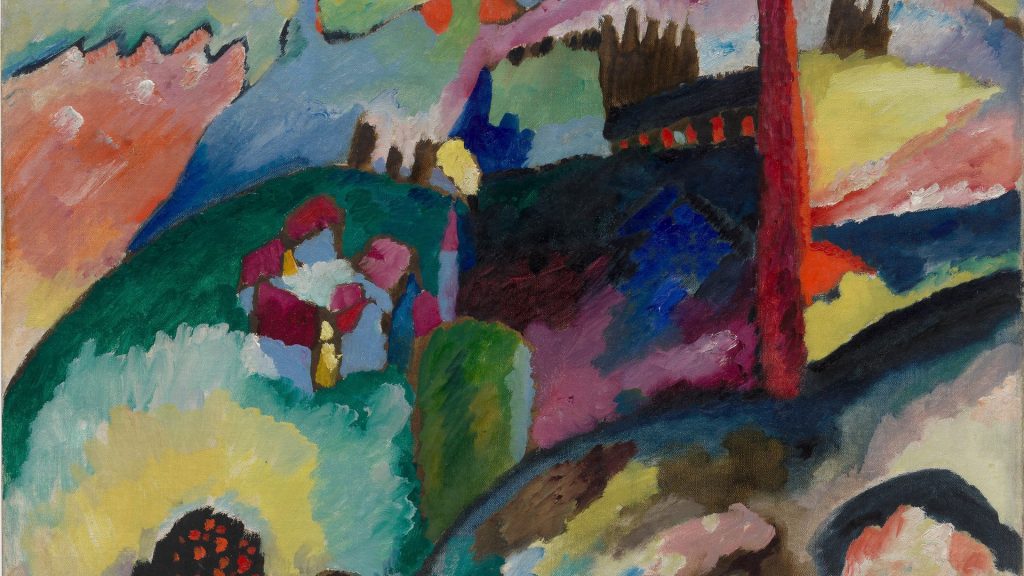

While dismissing as merely decorative art that were merely pleasing arrangements of forms, in Landscape with Factory Chimney (1910) Kandinsky began to fragment scenes.

Within two years, works such as Improvisation 28 (Second Version) and, in 1913, Small Pleasures, were marked by recurring but detached elements – hillocks, towers, questing lines.

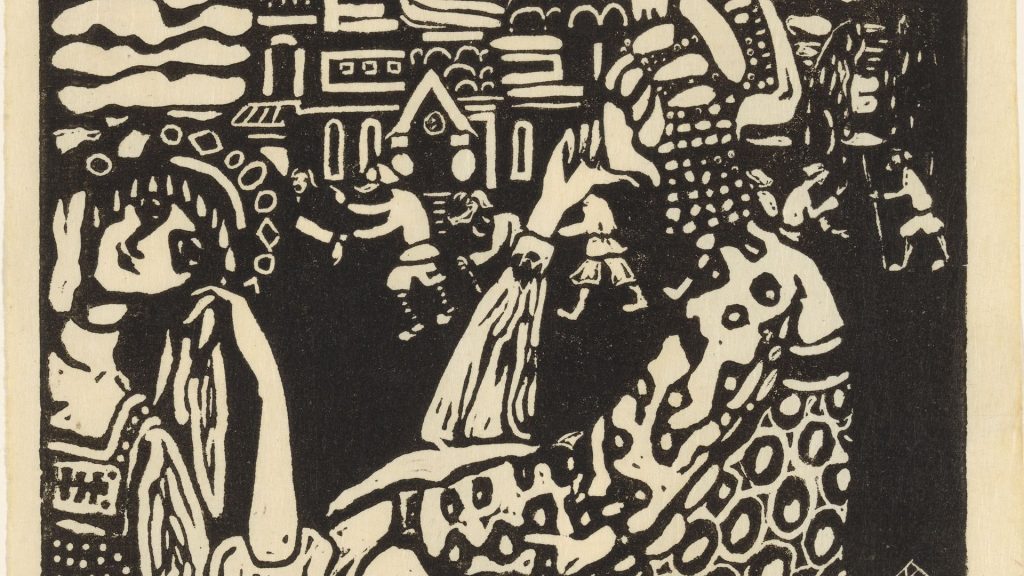

A familiar motif is the horse and rider, representing Kandinsky’s own crusade against convention.

With the German artist Franz Marc, Kandinsky founded the Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), an unstructured group of artists interested in the expressive potential of colour and the spiritual power of form.

Sometimes Kandinsky’s horseman was represented by his weapon, as in Painting with White Border (1913), where the busy world contained by the ribbon of white is pierced by a ghostly lance.

Other motifs were similarly refined – rolling hills were suggested by arching curves, trees are replaced by purposeful verticals.

At the outbreak of the First World War, the artist was obliged to return to his home country. There Kazimir Malevich, Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov were among the ground-breaking artists who were also experimenting with untethered forms – geometrical statements floating and clustering across the canvas.

From 1917, the year in which he married, until 1922, he was influential in teaching and curating posts until his work fell out of favour with the rise of Socialist Realism.

Returning to Germany in 1921, with his wife Nina, he continued to experiment with his visual lexicon, devising a loose vocabulary of form and colour.

The triangle embodied feelings active or even aggressive; the square stood for peace and calm; the circle was the supreme form, spiritual and cosmic. In the Black Square (1923) has echoes of Malevich, but Kandinsky’s quadrangle frames a symphonic explosion of fast-moving rhythmic forms and bold colour.

The following summer Kandinsky began teaching at the Bauhaus, where his work chimed with the rationality of geometric form.

He shared, too, with its other teachers, a belief in the transformative power of art in society. When the state-funded school fell victim to the Nazi government in 1933, its artists and architects scattered. Some, such as Josef and Anni Albers, sought a safe haven and new creative and teaching opportunities in the United States.

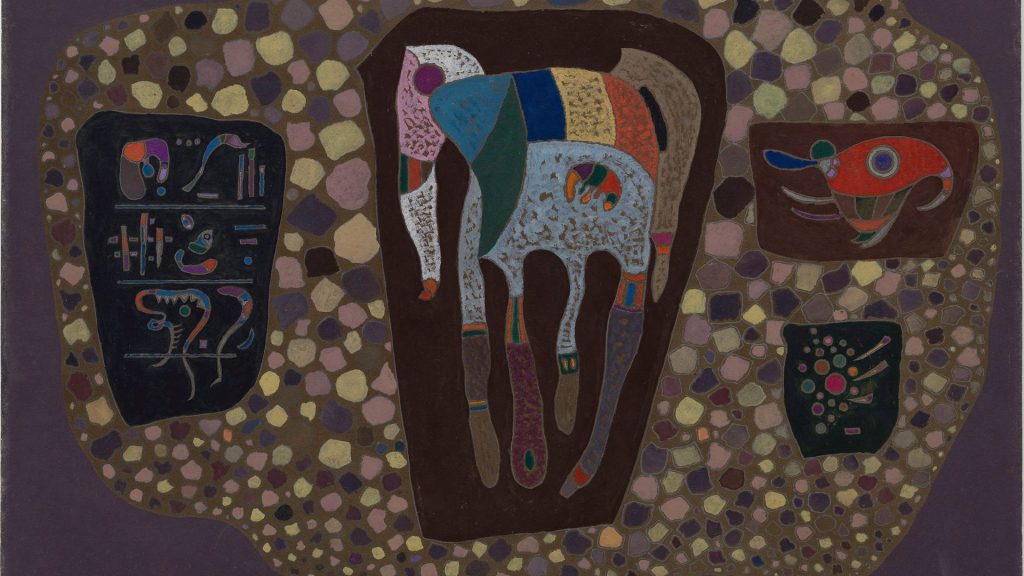

Kandinsky resettled in Neuilly-sur-Seine on the outskirts of Paris, where over his final decade fellow artists drawn to or resident in the capital included Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Fernand Léger, Joan Miró and Piet Mondrian.

Against the backdrop of a vibrant, urban arts life he further developed a growing interest in natural forms. He had collected natural specimens and scientific encyclopedias while at the Bauhaus, and now works such as Dominant Curve (1936) began to suggest a living world of living world with fleshy organisms and simple, soft-edged moving cells.

The final movement of his life’s composition had come full circle, from the natural world to an intellectual utopia and back again.

Kandinsky is at Museo Guggenheim Bilbao, until May 23 2021, and online