PETER TRUDGILL on how some unlikely connections between European languages emerged after 2,000 years

The Albanian word for king is mbret. You might think that this has got nothing to do with any word in any language that you have ever come across before. But it would be slightly surprising if you were right. Albanian is, after all, an Indo-European language, distantly related to English – and to most other European languages – although, like Greek and Armenian, it has no close linguistic relatives. Also, it has been spoken in the Balkans for a very long time indeed – probably at least as long as Greek – and has come into contact in that southern European peninsula with many other languages which it has been influenced by and borrowed words from.

From about 200BC, the Romans started becoming interested in the Balkans, partly because they were disturbed by acts of piracy carried out in the Adriatic from the western shores of the Balkan peninsula, and they invaded and gradually took control of most of the area.

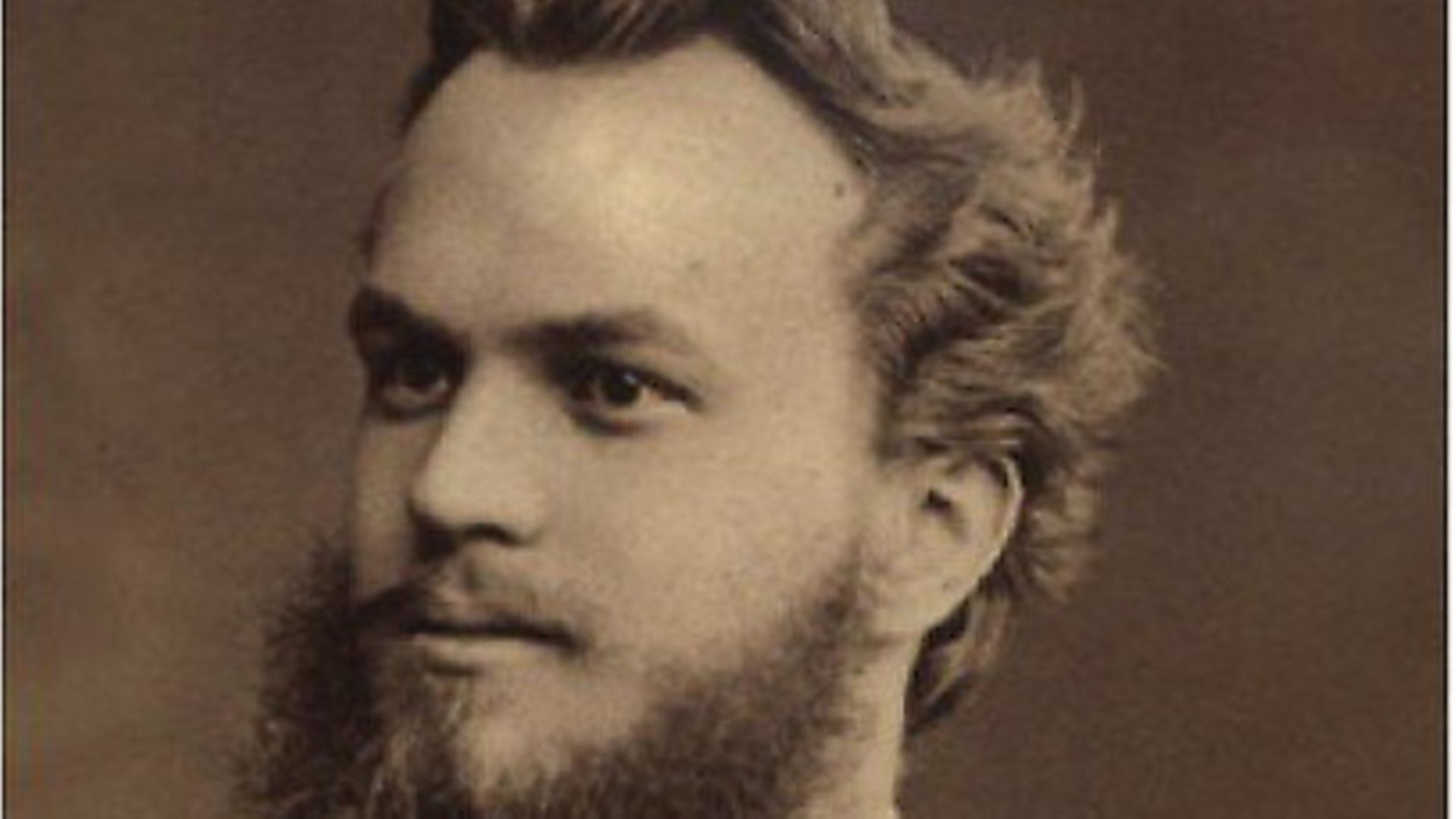

This eventually had interesting linguistic consequences. The Jirecek line, named after the Czech historian Konstantin Jirecek, pictured, divided the Balkan peninsula into a northern half, where the Latin language and Roman culture came to achieve dominance, and a southern area where the Greek language and Greek culture remained dominant in spite of Roman military and political control.

In modern geographical terms, the Jirecek line ran west to east across Albania, through the area of Skopje in North Macedonia, to Varna on the Black Sea coast of Bulgaria. The archaeological evidence which permitted Jirecek to locate the whereabouts of the line included the fact that most of the classical inscriptions that we are aware of in the northern area are written in Latin, while those to the south of the line are mostly in Greek.

The local languages in the zone to the north of the line were gradually replaced by Latin, which survives there to this day in the form of Romanian. But Albanian lived on, perhaps because some of its speakers lived in more mountainous or otherwise inaccessible regions – just as it survived the much later incursions from the north by the South Slavs, the linguistic ancestors of the modern Serbs, Croats, Bosnians, Montenegrins, Bulgarians and Slavo-Macedonians.

Not surprisingly, however, Albanian was still very much influenced by the Latin language, and even though it is not directly historically derived from Latin like French and Portuguese and Romanian, it now contains large numbers of words which were borrowed from the language of the Romans starting as early as about 100BC.

Some of these early loans have been altered so much in Albanian over the ensuing two millennia that they are difficult to recognise as such, and indeed were not widely recognised as Latin loans by linguistic scientists until the 19th century.

For example, the Latin word amicus, ‘friend’, has come down into modern French as ami, into Spanish and Portuguese as amigo, into Catalan and Rumanian as amic, and into Italian as amico. We, too, have borrowed this word into English in forms such as amicable. But speakers of Old Albanian borrowed amicus very much earlier than we did, and it has subsequently been radically transformed by sound changes in Albanian such as the loss of the first syllable. The modern Albanian word for ‘friend’ is mik. When we have been alerted to what has happened here in terms of sound change, we can see the word’s connection to, say, Romanian amic, but the link is not immediately obvious.

Similarly the modern Albanian word fqinj means ‘neighbour’. It was originally borrowed from Latin as vicinus, and so is related to the Romanian word vecin and to Spanish vecino, as well as less directly to English vicinity.

But what about mbret, ‘king’? Well, that’s easy once you know. Mbret is simply the Latin word imperator – ‘general, emperor’ – as borrowed into Albanian 2,000 years ago and transformed by natural processes of sound change in the language over the intervening centuries.

Emperor

In the 1200s AD, English borrowed the word emperor (from Latin imperator) from French. To the Romans, it had originally signified ‘senior military commander’. In modern English, it implies a particularly important kind of monarch. When Queen Victoria was declared ‘Empress of India’ in 1876, it was a kind of promotion.