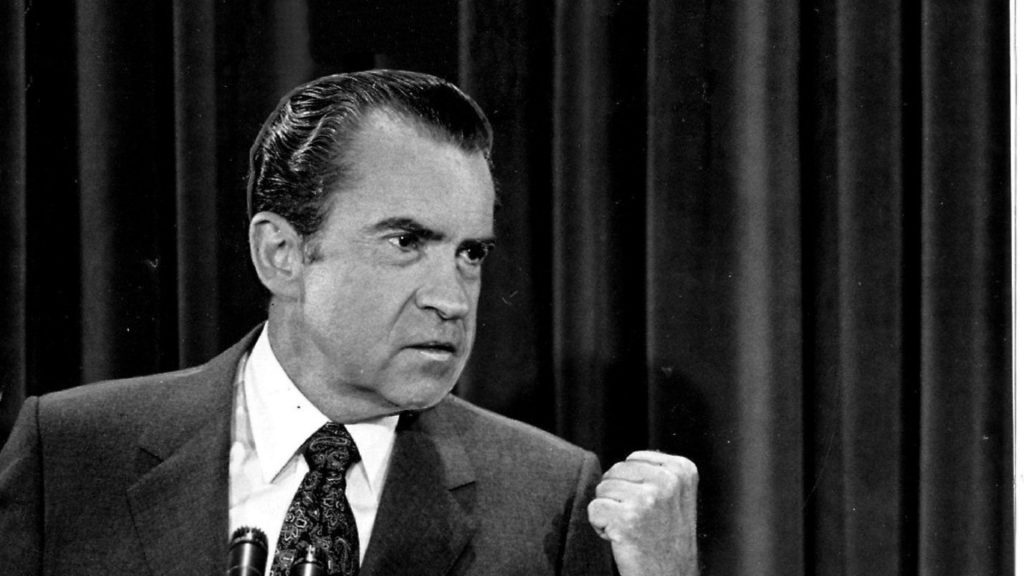

You can’t discuss Richard Nixon without mentioning his downfall. But on the 50th anniversary of his inauguration, IAN WALKER considers his other legacy, as the man who fired the first shots of America’s culture wars.

Monday January 20, 1969, was a cold, overcast day in Washington DC, for the inauguration of Richard Nixon as the 37th president of the USA. His address that day was epic stuff. A few weeks earlier the Apollo 8 astronauts had orbited the moon and become the first to see the earth as, in the description of poet Archibald MacLeish, ‘the bright loveliness in the eternal cold’. In his speech, Nixon quoted those words and, in poetic language of his own, juxtaposed the ‘moon’s grey surface’ with ‘the single sphere reflecting light in the darkness’.

The new president was using these metaphysical allusions as part of his statement of intent. He was going to be a great statesman, so great his ambitions could be measured against the scale of time and space. He would be the man who would try to bring peace to ‘the bright loveliness’, by thawing out the Cold War and ending the fighting in Vietnam.

Nixon also referred to the upcoming American bicentenary. If he were to be a two-term president, then he would be president in the summer of 1976, the 200th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Again, the president was projecting his ambition against the grandest gauge, this time against history and the unravelling of the future. In Nixon’s imagination, his aspirations and the ambitions of this 200-year-old experiment in human freedom and progress were the same. Nixon was America. Yet his concept was a particular idea of America.

In his address, Nixon may have been talking about the stars but he was positioning himself as a man of the people, a man of humble origins who had known poverty and suffering. He knew America, he claimed. He saw himself as the American Dream made flesh.

Nixon had made it. From a poverty-stricken, difficult childhood, here he was, on the east portico of the Capitol building, in front of the world, the new president of the USA; a populist with a philosophical bent, a politician with a poet’s understanding of the hidden patterns of history and destiny. He had beaten the naysayers. He’d shown all his enemies; all those East Coast, Ivy League sons-of-bitches, those Georgetown c**ksuckers, those liberal bastards at the NY Times and the Washington Post.

Richard Nixon was an especially thin-skinned man. In private he would rage against his critics, especially the liberal ones, using exactly those epithets – and worse. And the leaders of liberal America did hate him. Nixon did not imagine the sleights and the brickbats; the East Coast newspapermen, Ivy League academics and politicians, all loathed Nixon, and they had good reason. He began his career by firing the first shots in what became known as the culture wars. In getting elected, he destroyed his opponents, and he made post-war American politics terminally divisive.

Nixon began his political career in 1946 by running for Congress in his hometown of Whittier, California. He had just returned from the Second World War as one of the generation of young men who wanted to shape a new America, emerging not just from war but also the pre-war depression. And if Nixon wanted to make a political break with the past he had a perfect opponent.

Jerry Voorhis, a five-term Democrat, had been elected in the wake of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s interventionist plan to kick start the American economy in the 1930s. Voorhis was an out-and-out New Dealer. He was hard-working and popular on the Hill, including with some Republicans. At first, Nixon struggled to make headway against the incumbent, so, as a way of putting put some bite into his campaign, he called on the services of Murray Chotiner. Chotiner was one of the first professional campaign managers in American politics. He had been a lawyer before the war. His clients were mostly bookmakers and others who were, according to Chotiner, ‘unsavoury, to say the least’. In the 1940s he sidled his way into public relations and in 1942 he helped the Republican Earl Warren win the governorship of California.

Chotiner was a political thug. His motto was ‘Hit ’em, hit ’em, and hit ’em, again’, and in the Nixon campaign that’s what happened. Nixon attacked Voorhis by claiming, just as the Red Scare was starting to get traction, that Voorhis was a communist. He wasn’t, but having put this idea in the electorate’s head Nixon just kept plugging away at the idea, using every sleight of hand and every trick available. Voorhis was destroyed. Nixon went to Washington.

Later Nixon would say that ‘Of course I knew Jerry Voorhis wasn’t a communist, but I had to win’. And in 1950 Nixon did it again, this time against Helen Gahagan Douglas in a contest for the Senate. Nixon accused the former actress of being a communist fellow traveller and nicknamed her the Pink Lady (not quite ‘red’ but close enough). This was all happening just as America was going to war against communism in Korea. Nixon won by a landslide. He also won himself the new nickname Tricky Dick.

Nixon’s virulent anti-communism as a career-building strategy won him two elections, but more significantly it raised his profile to a national level in a very short period of time. In early 1947, he became a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). In the immediate post-war period, the committee’s task was rooting out communists from public life. And with the Cold War was in its early days, it was a perfect platform for a young politician on the make.

Nixon’s triumph was the Alger Hiss case. Hiss was handsome, suave, an East Coast leftist and Harvard Law School graduate: everything that Nixon hated. Hiss had risen as an attorney through various New Deal political institutions. In 1945, his involvement in international relations took him to the Yalta Conference, and he played a part in the creation of the United Nations.

Whether or not Hiss was a Russian spy is still debated, but in 1948 he was accused of being one by Whittaker Chambers, a former member of the American Communist Party, and brought before the HUAC. Hiss denied the charge and for a short while – mainly because he had powerful friends – it looked as if he had beaten the accusation. But Nixon – supposedly infuriated by Hiss’s condescension (in an investigative interview Hiss had said ‘I attended Harvard Law School, I believe yours was Whittier’) – refused to accept Hiss’s denial and doggedly kept working to bring him down.

Nixon won. Hiss was never charged with spying offences, but he was charged for perjury because he lied under oath. Idiotically, Hiss had tried to distance himself from any involvement in pre-war communist circles. There may be some debate as to whether Hiss was a spy, there is little debate that he had moved in left-wing circles in the 1930s. Hiss headed to jail. Nixon headed towards the White House.

Five years after arriving in Washington, Nixon was named as Republican candidate Dwight Eisenhower’s running mate for the 1952 presidential election. His rise had been extraordinary, at times even leaving John F Kennedy, that other golden boy of post-war American politics, in its wake. But anyone who rises that highly that quickly is going to make enemies and now Nixon’s enemies came very close to destroying him.

In attacking Voorhis, Douglas and Hiss, Nixon had been attacking the legacy of the New Deal, which had been, for millions of Americans, a necessary, even progressive, response to the failures of capitalism and the devastating Wall Street Crash. Its statist approach had also become the bedrock of America’s war effort against Germany and Japan. But as America geared up for its new stand-off with the Soviets, the New Deal’s statism looked, to some, a little too much like the collectivist approach of their new foes.

While commie-baiting played well with the electorate, and helped Nixon’s early political career, there remained a constituency of powerful, serious men and women who had steered America through a depression and war and who were revolted by the rabble-rousing and grandstanding of Nixon, McCarthy and the HUAC. They understood that it represented an attack on the New Deal and on progressive statism. Liberal America despised Nixon’s simplistic black and white – or red and white – view of geopolitics. So, right at the moment he was poised to become vice president, they went for him, wielding that most damaging of political weapons: financial allegations.

Nixon didn’t have any money behind him – all that stuff in his 1969 inaugural speech about being born poor was true. The home he lived in as a child was a self-assembly kit house bought from Sears. Without the wealthy background that sustains many ambitious American politicians, his Republican backers in California had set up a slush fund to pay for his travel, hospitality and other political expenses. Nixon also used it to buy a better house and a better car. The existence of the fund emerged in September 1952, as the White House race was intensifying, and Eisenhower came close to dropping Nixon from the ticket.

The running mate had one last chance, a television slot, where he would talk directly to the people and explain the slush fund. His subsequent appearance, which became known as the Checkers speech, remains a key moment in American – indeed, in western democratic – politics. It was perhaps the first time in the television age that populist emotion triumphed over facts. In this speech Nixon, talking directly into the camera, claimed that he had the same worries as the viewers: mortgage repayments, car repayments, buying a new winter coat for the wife. He was one of them, an ordinary man with ordinary problems. Yes, he received gifts, but one of these was a dog, named Checkers, for his daughters. What was he supposed to do? Give it back?

In this speech, Nixon left the newspaper editors, politicians and Ivy League academics with something they struggled to argue against. These serious men and women who had fought both economic collapse and the Axis were suddenly confronted with raw populism of the most devastating and insidious type. They were beaten by a dog. Facts meant nothing in the face of such emotive grandstanding. Nixon did not deal convincingly with a single accusation made against him but his approval ratings soared. Eisenhower kept him on the ticket. Nixon and Checkers were now an asset.

However, Nixon’s tenure as Eisenhower’s vice president, from 1953 to 1961, became the end of the first act of his political career. In 1961, Nixon was defeated by his Democrat rival John F Kennedy in the presidential race. The result was close and Nixon believed – with a fair bit of evidence – that Kennedy had cheated (there were accusations of ballot box stuffing in Illinois and Texas).

Following his defeat, Nixon spent much of the 1960s – the second act of his political career – trying to find a role for himself. He lost in an ill-advised run for the governorship of California (JFK burst out laughing when he heard news of his defeat); he moved to New York; he made a half-hearted attempt to start a law career; and he thought about running for the White House again in 1964. His only real achievement in this period was in assembling a team around him for when he did re-enter politics.

Otherwise, from 1961 to 1968, Nixon was irrelevant, which meant that during those years he played little part in the culture wars which tore America apart, and which he himself had helped to create. His 1946 campaign, with its vituperative anti-communist and anti New Deal language, had been a prologue to so much that followed: the Korean War, the Vietnam War, protests, riots, the Black Panthers, the Weathermen, the hatred at the heart of American political life.

What’s more, with his Checkers speech he had demonstrated that there was a silent majority, and that emotive populism could act as a bulwark against progressive politics. Nixon helped invent all that, and yet here he now was, an irrelevant laughing stock, shuffling about Madison Avenue, plotting, hesitating, prevaricating.

But the more desperate the second act reversal the more dramatic the third act denouement, and in 1968, Nixon’s return to politics was so dramatic it seemed almost staged. That year the culture wars were at their fiercest, with riots, military setbacks and political murders. Against this backdrop, Nixon saw his chance. He may have helped to usher in an era of ruptured politics, but he was not tainted by any of the consequences which raged throughout that tumultuous year. At the end of it, therefore, he emerged victorious in the election. Arms spread wide as he flashed the V for victory sign, Nixon was on his way to the White House.

Which brings us back to his inauguration and to the day where, as his chief-of-staff, Bob Haldeman, described it, it was as if Nixon ‘had light bursting from his eyes’. Nixon had an ideal of what a president should be, a grand ideal, which, in that inauguration speech, he measured against time and space.

He was a man who had made his own place in a country that had made its own place in the world. It was heroic stuff, here was his chance to be a great leader and a man of destiny. After the defeat to JFK and his wilderness years, he would do anything to take that chance. And that is where his troubles began.

For Nixon was not only a divisive politician who probably did more than any other to create the culture wars, he was also shaped by another division: one in his own head.

Nixon was obsessed with control – over himself and over the circumstances around him. Right from the beginning of his political career, he would fill up yellow legal pads with plans, insights, to-do lists and ideas. These notes would range from the quotidian (in one compiled for the 1946 congressional election he listed such things as having to get office furniture and bumper stickers) through to the big vision stuff, as he tried to define the kind of person and leader he wanted to be.

Nixon wanted to be a leader whose actions were born of consideration and reflection. It would be overstating it to describe him as an intellectual, but he had an intellectual way about him. There are descriptions of him as a socially-awkward young man who could stand in a crowded room, ignoring everyone, while lost in deep thought. One of the first things he did when he arrived in the White House was to timetable what he called ‘braintime’, which were his periods to think and plan.

This quasi-intellectual, measured, ‘big-stage/big-solutions’ vision that Nixon had for himself as president produced results. There was much about his time in the White House that was successful, and those successes came in ways that were not expected.

The Cold War warrior worked towards thawing the conflict as brought the USA and the USSR closer together. He also brought the USA and China closer together. (Indeed, you can trace the origins of China’s current economic dynamism to its being brought back into the international community by Nixon). In his first term, he oversaw demonstrable improvements in civil rights; he introduced unprecedented environmental policies, and he founded the Environmental Protection Agency; he invested heavily in research to combat cancer; he oversaw the reduction of the voting age to 18; he ended the draft; he used the money saved from reducing troop numbers in Vietnam on welfare; he gave Native Americans the right to tribal self-determination.

And he was as popular as almost any president had ever been. His landslide re-election in 1972 is still by was by the widest popular vote margin of any presidential race, nearly 18 million. He won every state bar one. This success was, in part, because his opponent, George McGovern, was hopeless (and was perceived as leading what was left of the counter-culture), but Nixon was undeniably a popular and, at times somewhat surprisingly, progressive president, who appealed to the centre ground.

But, of course, Tricky Dick isn’t famous for any of these things. He is not one of history’s good guys. Another factor in his greatest success – that resounding re-election – was his cheating. Fearing that Maine senator Edmund Muskie would be a strong Democratic candidate in the 1972 campaign, Nixon’s Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP, or CREEP, as it became better known) forged a document, the so-called Canuck letter, suggesting that Muskie had a prejudice against French-Canadians. Muskie’s reaction – he was said to have been cried – as he rejected the contents of the letter and separate allegations about his wife, destroyed his chances of becoming the Democratic candidate. It was just one example of a pattern of cheating that would later emerge.

This was the other side of the division within Nixon. The visionary politician with an idealistic belief in the USA and in the role of the president and in himself, was also a pathologically paranoid, brittle man. His instinct to always be in control, which drove his ambition and shaped his success, had a dark side.

It wasn’t just that he had to beat his political enemies, Nixon had to destroy them. To do this, he had to know what they were thinking and pre-empt their attempts to get at him. This is why Nixon sanctioned the bugging of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate building, and this is why, once the Washington Post began investigating the story, following the arrest of those who did the bugging, Nixon made things much worse as he fought his enemies with lies and deceit.

Much later, right at the end of the third act of Nixon’s political career, as everything was unravelling in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal, Caspar Weinberger, who had served as his director of the Office of Management and Budget, would say of him: ‘All that talent – all those flaws.’

So where did those flaws come from? One theory is that it went back to his traumatic childhood. Nixon’s father was a failure and a bully and his five sons were terrified of him. His mother, a Quaker, was a kind but distant woman who was never quite there for her sons. But the real trauma of his childhood came with the death of his younger brother, Arthur, who was just seven when he died of meningitis. Nixon was 12. He had been protective of his younger brother; his fraternal love had intensified as he instinctively tried to compensate for something lacking in a house devoid of paternal love and full of paternal violence. But that protection meant nothing against the random disease that killed Arthur.

Nixon was raised as a Quaker and never renounced religion, but his view of God settled on what is sometimes described as a cold Deism. God created everything but after that we are on our own. Left alone, all that can happen in this universe – including the death of a child – is arbitrary. So you don’t leave it alone. Human agency, ambition, planning and politics is the struggle to impose order on all that is random in an indifferent universe.

That was Nixon’s worldview. He believed that our values and our civilisation – the very existence of the USA – was humanity imposing order on the chaos. It’s no wonder that he was so thrilled by Apollo 8: it was the literal, physical act of meaning being created in the void. And it was no wonder that he was so thrilled by the ideal of the presidency which he saw as the creation of meaning in the face of an unknown future. But while this instinct to impose control and order was the source of Nixon’s idealism, it was also the source of his undoing – because there wasn’t much he wouldn’t do in service of it.

The final unravelling of Richard Nixon began with the so-called Pentagon Papers, an official report detailing America’s political and military involvement in Vietnam in the 1960s, and showing how the American people had been lied to by the White House.

In 1971, documents from the report were handed to the New York Times and the Washington Post by a man named Daniel Ellsberg. Initially, Nixon was indifferent to the leak, since it discredited his predecessors. But the Pentagon Papers exposed something else too. Suddenly, the American people had a glimpse of the ugly, cynical, inner workings of power. Nixon, a man who had a genuine and idealistic belief in the presidency (and also scores to settles with the Times and the Post), grasped that point quickly. So he acted and in doing so he made everything much worse.

As the scandal over the Pentagon Papers broke, Nixon’s staff created a covert unit known as the Plumbers. These were a group of political operatives, former CIA men and Cuban exiles whose job it was to protect the White House by plugging all leaks and ensuring there was no Pentagon Papers equivalent under Nixon.

Yet like CREEP (the two bodies were pretty much the same people), they disastrously overstepped their remit.

This is where the divisions that lay within Nixon become more historically significant than the divisions that he had helped create within American politics. His instinct for order and control just intensified as everything collapsed around him. And the more that order and control failed him, the more he railed at the East Coast, Ivy League sons-of-bitches, those Georgetown c**ksuckers, those liberal bastards at the Times and the Post. He also, in his paranoia, in this, his final third act collapse, railed against the Jews. All of Nixon’s idealism, all of his achievements were undone. He destroyed himself. On August 9, 1974, Nixon resigned in disgrace.

He deserved his fate. If anything, he deserved greater punishment than he received (he was pardoned by his successor, president Gerald Ford). But there is certainly something tragic about the man. Nixon’s greatest qualities – and he had great qualities – and his worst qualities came from that same place, from that desire to impose order and meaning on events. His fatal flaw was that as this driven politician, with dreams of greatness, fought to shape history, this psychologically-damaged man could not tell the difference between what was a lie what was true, what was right and what was wrong. He could have been a great president but the man got in the way.