A new film about the touching relationship between the singer and writer and Marianne Ihlen, the muse he met on a hippy hideout in the Mediterranean, comes with an added twist- Director Nick Broomfield was also her lover. He talks to JASON SOLOMONS.

For a documentary film maker Nick Broomfield is a ubiquitous character. He’s always inserting himself into his films, becoming familiar in the 1990s for appearing in his white T-shirt and jeans, holding a boom mic, chunky tape recorder slung over his shoulder while confronting, say, a serial killer (Aileen Wuornos in The Selling of a Serial Killer and Life and Death of a Serial Killer), a volatile rock goddess (Courtney Love in Kurt & Courtney) or a Hollywood whistleblower (remember Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madame?).

His insertion into the love story of Marianne & Leonard, however, takes things to another level of personal involvement and results in Broomfield’s most emotionally powerful and beautiful film yet. I think it’s one of the year’s best films, too.

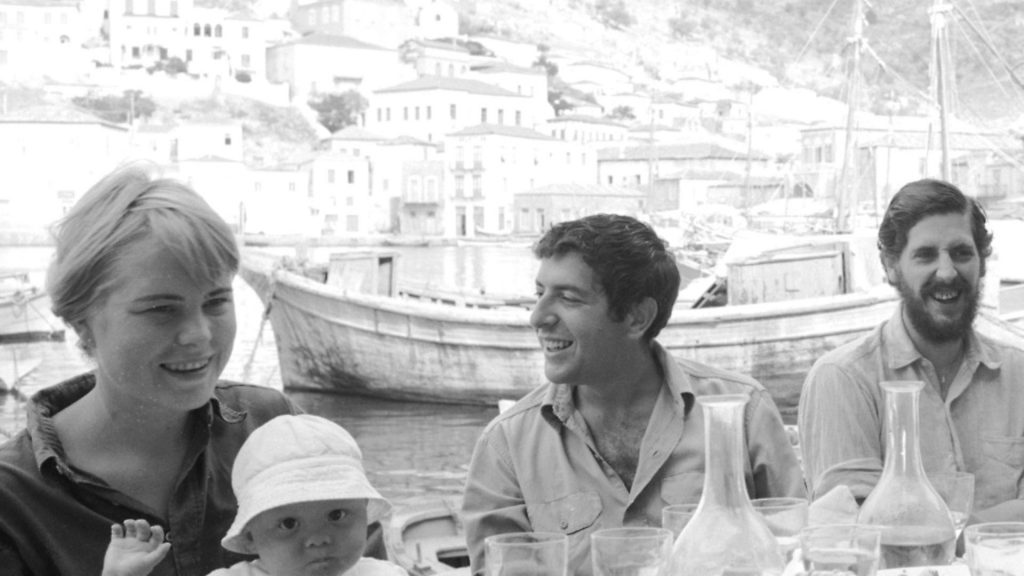

Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love charts a 56-year romance, between singer Leonard Cohen and a Norwegian beauty called Marianne Ihlen, a woman who became Cohen’s muse and the subject of one of his most famous and most tender songs, So Long Marianne. She was also, briefly, the young Nick Broomfield’s lover.

“It’s certainly the film I’ve been most personally involved in, from a romantic point of view at least,” says Broomfield who, in truth, has been making fewer on-screen appearances in his recent films.

“It wasn’t that I was desperate to get back on screen or anything but simply I didn’t really think I could tell the story of Marianne without mentioning my involvement. Because I was intimately involved with her and she spoke about him so much, I knew the story so well. I tried to leave myself out of it but then realised there’s an extra value for the truth of the film that the storyteller was actually there – it gives it an unusual dimension, something very intimate.”

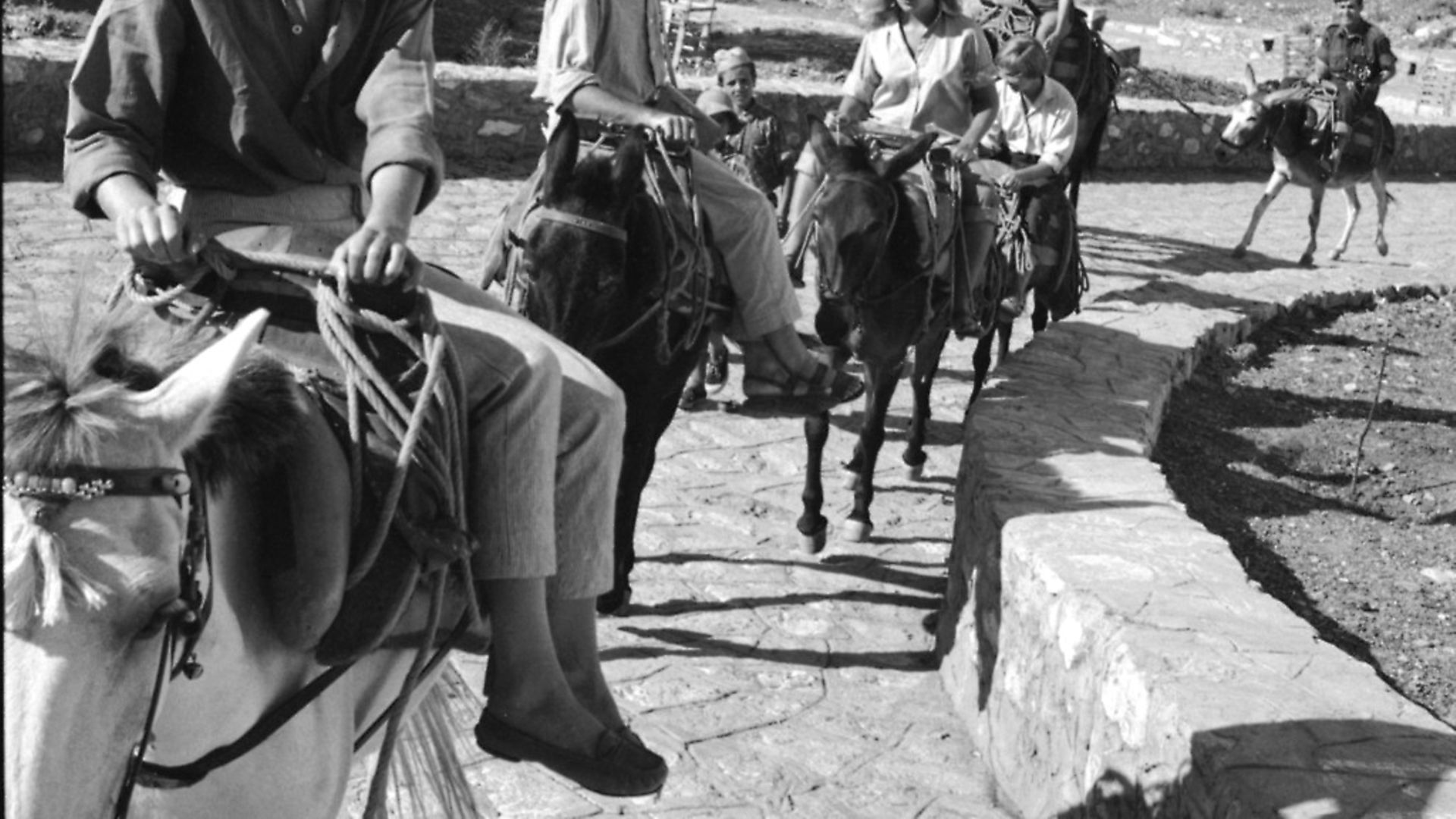

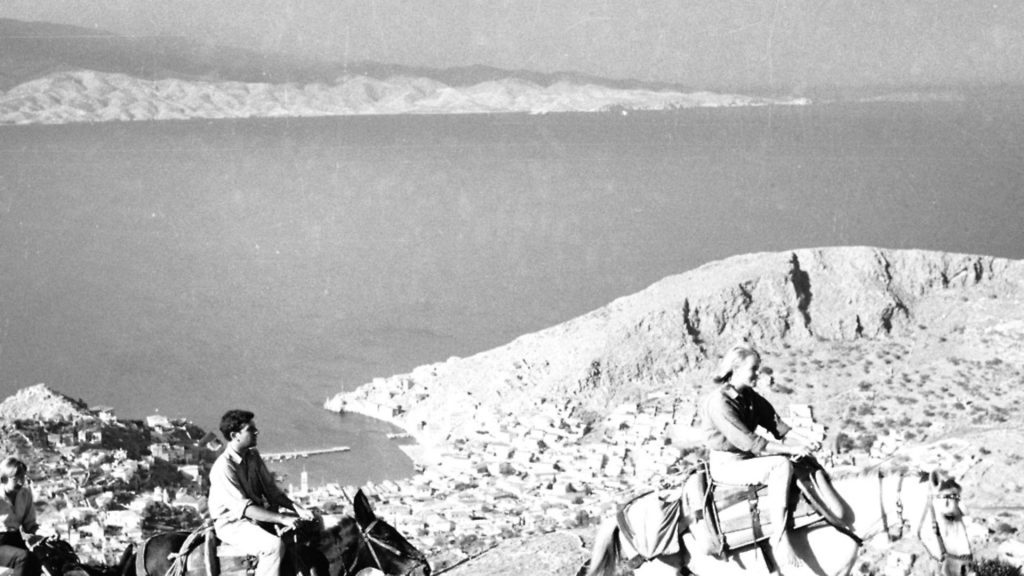

The film centres on the Greek island of Hydra, which in the early 1960s was colonised by artists and poets and hedonists who created a commune of free love, drink and drugs there. It was a brief utopia of, as a friend of Marianne’s, interviewed in the film, recalls: “Writing, lovemaking, bathing and drinking and talking in the sun.”

It was there that Leonard Cohen, fleeing the cold constraints of Montreal bourgeois life, met Marianne in 1964 and it was into this idyll that the young Nick wandered in 1968.

Broomfield narrates the whole story without actually straying into shot, although there are photos of him as a young man, personal reminiscences and clips of his early film work – work which, he confesses, he would not have made without Marianne as inspiration.

“Hydra and Marianne had such an influence of me,” he reflects, almost wistfully, that familiar, honeyed voice cracking slightly.

“I thought it was a model for living, that this was how I should live my life from now on. It was, for a while, total bliss.”

Broomfield reveals that it was Lindy Runcie, wife of the future Archbishop of Canterbury Robert Runcie, who sent him there. They’d met on a cruise Broomfield was taking with his parents on a break from his law studies. As he recalls now, with some surprise: “She was the life and soul of the party on a rather dull ship but she told me I must visit Hydra – she wasn’t very upright and Christian, as I recall but actually very defiant and radical and she seemed to know all about Hydra.”

What was the scene that met the young traveller, then? “Gosh, as soon as you got off the ferry you were greeted by someone from a particular pension (guest house) and if you were fancied, if they liked the look of you, their scout would choose you for their little pension.

“You didn’t have much say in the matter, I suppose. I ended up in one that was affectionately known as The Sin Bin, a place that was so full of people of both sexes having sex and doing whatever they wanted, that I had to sleep in the oven one night, an old baker’s oven in the kitchen.”

He believes Marianne knew the owners of The Sin Bin and heard about the new arrival, the new young Englishman. “Before I knew it, I was sort of summoned, or visited upon…” Broomfield re-enacts a shocked double-take: “I was 20 years old and this drop dead, beautiful blonde is showing some interest in me and I thought: ‘Wow, me? really?’ Honestly, it was like Christmas had come. I couldn’t believe my luck so, you know, I sort of got on with it, went with it.”

Didn’t he mind that she was known to be Leonard Cohen’s girlfriend? “Well, nobody seemed to mind that out there. It wasn’t an issue.”

And didn’t he mind that she kept going on about Leonard the whole time? “Ha, not a bit – it was like ‘words from the great man’, you know? His first album had come out in 1967 and it was now 1968 and suddenly I was given this entree to a very connected, international crowd of artists and poets and drugs and I was reading about RD Laing and thinking about things in a totally new way. People seemed to be always popping off to India and coming back from India with more drugs.

“Hydra was a key stop off on the hippie trail and, without doubt, it changed my life. This hedonistic, intoxicatingly beautiful place that was so simple: No cars, only mules, all whitewashed under this amazing sun and amazing swimming spots…” Again, Broomfield drifts off, as if in reverie.

So this is a good place to return to the actual finished film which, far from sticking with the Zelig-like Broomfield, tells it through the eyes and mouths of many others who were also there.

Cohen, like many, found on Hydra the flip side to his life, refuge from a respectable Jewish family from Montreal. Somehow he found himself on this sun-drenched, time-forgotten isle and plunged into the micro-world of artists and lotus-eaters who had gathered for an alternative lifestyle.

If it all sounds rather insufferable – a sort of 1960s Love Island, only with people who can actually read – Broomfield’s film does convince you of its magic and capture the idyll, the allure of the waters and the beauty of the skies. It looks, and feels, like the best summer holiday ever.

Cohen wrote his novel Beautiful Losers there, tapping away in the scorching sun through the summer of 1966 while Marianne took care of the lunches and the drinks. She was with another man when Cohen arrived, and had a son who every one called (and still calls) Little Axel, but her previous life seems to have been easily shed when she took up with Leonard, who was clearly charming and bright and reasonably handsome, although not yet any sort of singer.

As the film tells it, it was only in 1967, on a return to Montreal, that Cohen suddenly re-invented himself as a singer, fitting the words of a poem, Suzanne, to music. He originally wanted Judy Collins to sing. But once he’d overcome his nerves and reservations about his own voice, Cohen was an instant success, up there with Bob Dylan and Paul Simon amid the Jewish folk heroes.

Broomfield’s arrival doesn’t alter the course of the film as much as it did his real life. The story remains focused on Leonard and Marianne, even as they drift apart and the skies darken.

Using faded photographs, bleached out home movie footage and the recollections of some Hydra survivors, Broomfield summons up that atmosphere of indulgence and bliss, but soon ushers in clanging notes of despair.

As Broomfield notes now: “It was Leonard himself who said ‘Once you’ve lived on Hydra, you can’t live anywhere else, including Hydra’.

“The lotus-eating takes its toll. I went back there a few weeks ago to show the film – they have an amazing open air amphitheatre where you can screen after dark – and there are a few survivors of that time.

“Only the very disciplined came out well, those who had a strict schedule. Actually, as I recall, Leonard was very dedicated to work. Even when out of his mind on acid or Mandrax, he’d have the typewriter in front of him and let it pour out in words.”

Cohen’s long absences take their toll on Marianne, just as the drink, drugs and free love have an impact on almost everyone on the island. Cohen seems to have taken the promiscuous mindset of Hydra on the road with him and he is shown with women in every city. As an associate puts it: “He had an appetite for the sexual expression of friendship.” Once, in Amsterdam, he invited the whole audience back to his hotel room for a love-in. Someone rightly sighs: “Thank god it was the 1960s, you know?”

Darkness and depression seep in. Cohen holes up with Janis Joplin in the Chelsea Hotel and won’t allow Marianne to even visit. There’s a cruelty to it all and yet, her heart on the verge of breaking, Marianne clings to her idyll, to Hydra. Leonard Cohen does too, even on his 23-day-long acid trips, as detailed by band member Ron Cornelius. How reliable a witness anyone is to some of this is, of course, debatable.

Marianne doesn’t look like a victim, although I confess I felt for her in her various muse guises – hurt muse, spurned muse, even abused muse? But as Cornelius remarks in the film: “Leonard was on some kind of quest, chasing something. But I don’t think he knew what he was looking for. He lived in darkness and depression and he wrote songs for the quasi-depressed.”

The film follows Cohen into a tumultuous period recording with a cracked Phil Spector in LA, a time of guns, drink and madness that resulted in the notorious album Death of a Ladies Man (1977) and then a period of withdrawal that saw Cohen exile himself in a Buddhist monastery without ever releasing his most famous song, Hallelujah.

It’s very skilfully put together and Broomfield never loses sight of the love between Marianne and Leonard, tracing its continuation right through to both of their deaths, only a few years ago. (Ihlen died in July 2016, Cohen little over three months later.)

It’s impossibly romantic, which isn’t the sort of thing one usually says about a documentary, but you never feel he’s straining to make the point.

Was it a better life, back in the free love 1960s, back on Hydra? “It’s an unsustainable one,” says Broomfield. “Free love eats you up – both parties, I think. But it’s very poetic. You watch the film and all the great loves come back to you – it’s evocative of all those things for many people, and it’s satisfying to make a film about that and I’ve found people end up sharing very intimate thoughts with you after seeing it, telling you about affairs they had.”

What does Words of Love say, then, about the nature of love? “Well, that’s what I set out to examine,” he says. “This is a love affair where both hurt each other – so what sort of love is it? I would say it’s an enduring love, and recognition of a profound love you’ve shared even if it’s in a different chapter to when it was red hot.

“I think Marianne saw Leonard through transition from a failed writer to someone who found an incredible career putting music and words together. She helped him find disparate parts of himself that he didn’t believe in and that she encouraged – and he cared for her and her son when she needed it. They had deep respect for each other’s hearts and that’s what is so beautiful.”

I don’t want to spoil the ending of the movie, but you won’t find many more moving passages in documentary-making. Leonard and Marianne, even through the heartache, clearly had a pure and true love and this gorgeous, reflective, sunlit movie will prompt anyone who sees it to look back and re-evaluate their own love stories – from long marriages to holiday romances that can last a lifetime.

Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love is released in the UK on July 26.