Brexit is only one chapter in the story of Britain’s retreat from influence, says JOHN KAMPFNER. We now face a marathon journey back to our rightful place

Compare and contrast two events, two eras. Mid-May 1999: amid the splendour of the City Hall in Aachen, the ancient German city that borders Belgium and the Netherlands, Tony Blair was receiving the Charlemagne prize, awarded for service to the unity of Europe. He was following in the footsteps of Jean Monnet, the brainchild behind the European Union, Vaclav Havel, Helmut Kohl and Winston Churchill.

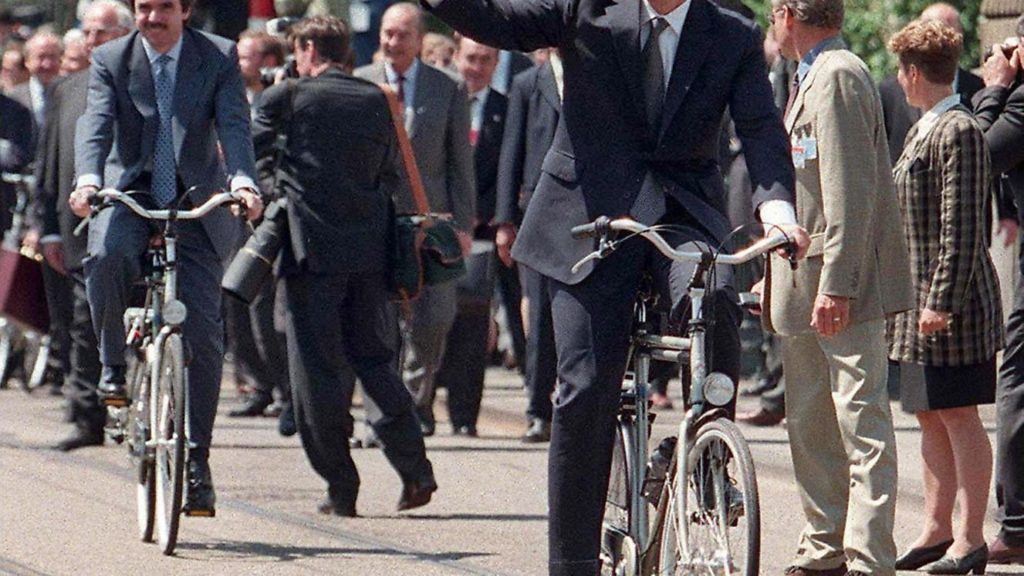

The UK, he declared, must shed its ‘ambivalence’ towards Europe. Europe, he said, must show greater steel in the face of dictatorships. Wherever the British prime minister went, he was feted. He was the new kid on the block, millennial man, de facto king of Europe. At his first summit, EU leaders were invited to set off down an Amsterdam street in unison for a photo call. They indulged Downing Street officials and let Blair go in front. The message was: the Brits have caught up with us, and are even setting the pace.

Now look. Brexit may be responsible in very large part, but the diminishing of Britain had started before. Iraq didn’t help – George Bush, with Blair by his side, dividing the continent into New Europe and Old Europe. As Blair’s enthusiasm for the European project waned, so business returned to usual. Gordon Brown slowed it down further. We retreated to our default position, the island nation, wagging our fingers, waving our plastic union flags and obsessing about past glories. Fog over the Channel, Europe cut off.

In 2014, one episode demonstrated our marginalisation with painful clarity. Russia had fomented an uprising in eastern Ukraine. In Kiev, the pro-Moscow leadership was being forced out by a pro-democracy uprising. It was time for the EU to step in and preside over crucial peace talks. Leading this were Germany and France – so far, so unsurprising – and Poland. Britain was nowhere to be seen. One might argue, with a certain justification, that the Poles had an important regional role to play, with their historical links to Ukraine. But that would be to ignore the bigger point: the UK was no longer seen as part of the engine room of Europe.

David Cameron was left to issue a statement praising the work of his EU partners. That was one year before the general election and his foolhardy decision to commit himself to a referendum. The rest, as they say…

The notion of Britain going it alone, without Europe, was always based on two fallacies. The first was that we would rise again as a Singapore or Dubai on the Thames. That might be all well and good, except that even for a Conservative government promoting the virtues of austerity, such a model would have required a dismantling of the last vestiges of the welfare state.

Theresa May demonstrated no inclination for that. Rather the reverse: her little-heralded Red Toryism suggested a move away from low-tax libertarianism so beloved of right-wing think-tanks. The other fallacy was the so-called special relationship with the United States.

I have lost count of the number of US diplomats who would give me a wry smile at the very mention of the phrase. That’s our favour to you guys, was the message. It’s all nonsense, but we’ll do what we can to make you feel good about yourselves.

Blair’s post 9/11 alliance with Bush was a last-gasp attempt to keep alive an idea that was long past its sell-by. Barack Obama pivoted towards Asia and just about made it over to cook burgers with Cameron on the Number 10 barbecue. As for Donald Trump, he doesn’t think much of the present incumbent – for all her faults, Theresa May is not the kind of dictator and human rights abuser that the president has a soft spot for.

Hence not just sadness, anger and frustration in European chancelleries, but consternation. The manner of the agreement by the EU27 spoke volumes. Annoyed that their Sunday had been disturbed, they spent less than an hour approving it last weekend. Desultory was perhaps the most appropriate adjective.

What did we Brits think we were playing at? We have good intelligence, an admired cadre of diplomats, so how come we chose – to coin a phrase – to give up on the worst alliance, except all the others that were available?

The chronology of Britain and the EU has been one of discomfort and threats. No sooner had we joined in 1973, we were wondering whether to head for the door. No sooner had that been settled in 1975, Margaret Thatcher started to throw the toys out of her pram. She achieved the rebate, she said up yours to Delors, but still we weren’t happy. Even outside the euro and Schengen, we wanted more. The biggest irony of all was our insistence on broadening to the former Communist countries of the East, who would flock over to us, leading to the fears about freedom of movement about which the PM so obsesses.

Now, even if the stars aligned – the Withdrawal Agreement was voted down, a People’s Vote was held, and the country voted to reverse the 2016 decision – what would be our relationship with Europe? Why would they want us back? There are reasons to suggest they would. Even with the rebate, our financial contribution is significant. Our military and security roles remain important.

We are still, thanks to quirks of history, a permanent member of the UN security council. We are a key player in NATO. Our intelligence gathering is highly respected. Even in the midst of Brexit chaos, the government achieved a significant victory over the Kremlin by bringing the rest of the West alongside in its response to the Skripal case. And economically and culturally, we provide a counter-balance to the countries of the south.

Yet our withdrawal has already been factored in. The EU budget has been adjusted. Although France and Germany remain the hub, with or without Macron and Merkel, the geometry of the union is constantly shifting. Populist governments in Italy and Hungary and beyond pose a more pressing threat to European harmony than sulking from Britain. As for security, mutual self-interest suggests that cooperation will continue, no matter how fraught relations might become.

The early Blair era is already taught as history in schools. It belongs to a different era, when Europe dared to hope that we had moved on from our Dad’s Army days. Over the last decade, we have retreated back into the margins.

For those at the heart of 21st century Britain – people involved in science, or academia, or culture or tech – the divorce is made all the more painful by the tone of our interlocutors. Every speech or conversation from the visiting delegation begins with a lament to ‘our British friends’. The tone is in part patronising, in part genuine and caring. Would they bring out the bunting if we applied a handbrake turn? European chancelleries would have us back, but it would be the wariest welcome. They would want reassuring that we had finally reconciled ourselves, long-term, as a nation to a life in the heart of Europe. And the chances of that happening? Think second referendum victory and multiply that by a factor of hundreds.