Cosy crimes? The novels of Agatha Christie are dark and political– that’s why, almost a century after the first one was published, they appeal so much to modern filmmakers. LUCY SCHOLES reports.

Rian Johnson’s new film, Knives Out, is a glorious black-comedy romp of a whodunit, set in contemporary America but steeped in all the traditional elements of the genre. The wealthy, hugely successful crime novelist Harlan Thrombey (Christopher Plummer) is found dead, his throat gruesomely slit, the morning after his 85th birthday party. As far as the police – headed up by Lieutenant Elliott (Lakeith Stanfield) – are concerned, it looks like suicide, but why would Thrombey, a man at the height of his power, want to kill himself?

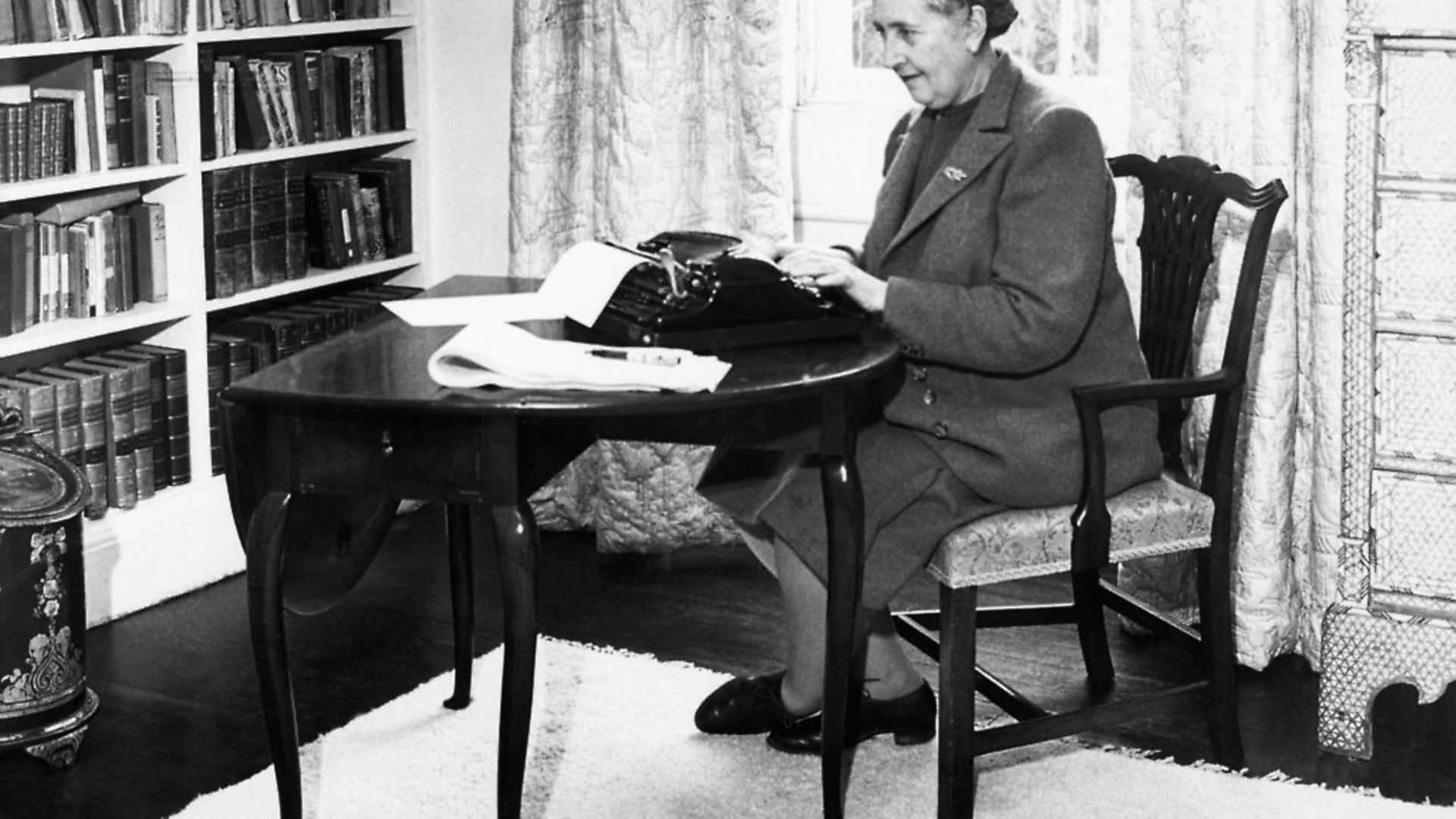

Like murder, Agatha Christie never goes away. Her books live on by themselves, of course, still selling in wholesale quantities. But they’re also supported by a steady stream of adaptations, such as the BBC’s forthcoming The Pale Horse, and quasi-adaptations, such as Rian Johnson’s current Knives Out.

He lives in a large, gothic Victorian mansion, all elaborately carved staircases, concealed doors and hidden passageways, the rooms resplendent with ornate, amazing artefacts, from suits of armour through baroque displays of antique daggers. As Elliott sums it up, “The guy practically lives on a Clue board.” Even before the appearance of the sharply dressed Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) – “the last of the gentleman sleuths,” according to a recent New Yorker profile – puffing on a cigar, his Louisiana drawl as smooth as the reputation that precedes him, the audience knows exactly what they’re watching. “I suspect foul play,” – Blanc twangs, and the game is afoot!

And what a cast of suspects Blanc is presented with. There’s Thrombey’s haughty daughter, Linda Drysdale (Jamie Lee Curtis), who insists on describing herself as “self-made” despite the million-dollar loan from daddy that launched her business; her devious idler of a husband Richard (Don Johnson); and their son Ransom (Chris Evans), a spoilt, rakish rebel without a cause and a foul mouth. Thrombey’s son Walt (Michael Shannon) supposedly presides over his father’s literary empire but is clearly little more than a gutless lackey who can’t even control his own teenage son (Jaeden Martell), a creepy neo-Nazi who spends all his time in alt-right chatrooms.

Then there’s Thrombey’s widowed daughter-in-law Joni (Toni Collette) a wannabe wellness guru in the vein of a wide-eyed Gwyneth Paltrow, with wildly expensive tastes and a daughter (Katherine Langford) whose exorbitant university fees need paying. Everybody is dependent on Thrombey’s generous handouts, which, coincidentally, the much put-upon patriarch had suggested were about to cease. Given his family’s greed, and enough backbiting and one-upmanship to make the Logan clan in Succession look like the Waltons, everyone has a motive for the old man’s murder.

These cornerstones of the genre – the country house; the crime that’s clearly an ‘inside job’; the celebrated professional sleuth; and a big theatrical reveal that involves a final, gasp-inducing plot twist – were all established back in the 19th century with the publication of Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone (1868), the book that is now widely considered to be the first modern detective novel. But if there’s a novelist who deserves credit for ensuring these elements are now eponymous with the genre, it has to be Agatha Christie.

It’s one year short of a century since Christie published her first work, The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), a novel that, despite having started life as something of a joke (a dare proposed by her sister, Madge), set the gold standard for the genre. It has all the key ingredients, plus it introduces us to Christie’s most famous creation: the private detective extraordinaire Hercule Poirot, a Belgian ex-police inspector, recently arrived in England as a war refugee. A fictional character of such fame that the New York Times published his obituary in the summer of 1975, slightly ahead of the release of Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case, a film which sees both the super sleuth and his old friend Hastings come full circle, back to Styles, where’s there’s one last murder to solve. (Blanc’s New Yorker profile is surely director Rian Johnson’s nod to this rather fun bit of Poirot trivia.)

The Mysterious Affair at Styles was just the first of Christie’s many closed-circle mysteries set in a large family home. Over the course of her long and prolific writing career, it was a model she would return to again and again, always extremely successfully. Novels like Crooked House (1948), They Do It With Mirrors (1952), A Pocket Full of Rye (1953), and 4.50 From Paddington (1957) were second only to the likes of The Murder on the Orient Express (1934) and And Then There Were None (1939), both of which are inspired twists on the set-up.

In the former, an American tycoon is stabbed to death in his compartment on the world’s most famous train, while it’s trapped in a snowdrift, high in the mountains, thus Poirot’s pool of suspects is limited to the other passengers. In the latter, ten people – each of whom is hiding a dark secret – are invited to an island just off the south coast of England. Once there, however, they find themselves marooned, cut off from the mainland and with no means of escape, reminded of the sins they’ve committed, before they each meet a grisly death, picked off one by one, the dwindling group of survivors driven mad trying to work out which of them has appointed themselves judge, jury and executioner.

Christie’s record-breaking is common knowledge. Her books still sell more than 600,000 copies a year – outranked by only the Bible and Shakespeare – and have been translated into over a hundred languages. Her play The Mousetrap is the longest-running show in the world, having never left London’s West End since it premiered in 1952. She isn’t just the Queen of Crime, she’s also a cultural touchstone. (Earlier in the autumn, Coleen Rooney, wife of footballer Wayne Rooney, won the inspired moniker “WAGatha Christie” after she took to Instagram to explain the complex sting operation she’d orchestrated in order to unmask the person close to her whom she believed was selling stories about herself and her family to the media.) The fact that Christie’s books have been the subject of more than a hundred TV adaptations, and 30-plus feature films, only adds to her extraordinary legacy.

While Knives Out isn’t a strict adaptation (fans of Christie’s work will recognise some similarities between Johnson’s plot and that of Christie’s Crooked House), it is both loving homage to her and a work that’s crying out for a famous ensemble cast, something that Christie’s novels offer up, again and again. The most famous example is Sidney Lumet’s 1974 adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express, which featured, amongst others, Lauren Bacall, Ingrid Bergman, Jacqueline Bisset, Sean Connery, Albert Finney, John Gielgud, Anthony Perkins, Vanessa Redgrave and Michael York.

This star-studded cast was repackaged for contemporary audiences when, in 2017, Kenneth Branagh directed – and starred in – his own adaptation of the novel, alongside Olivia Coleman, Penélope Cruz, Willem Dafoe, Judi Dench, Johnny Depp, Derek Jacobi and Michelle Pfeiffer. That same year, Gilles Paquet-Brenner’s adaptation of Crooked House featured Gillian Anderson, Glenn Close, Christina Hendricks, Max Irons and Terence Stamp.

Yet, while Christie’s a world famous, bestselling author, beloved by readers of all ages and of all backgrounds, there’s long been a strange disjunction between the darkness of the plots of her novels, and how she and her work is portrayed in popular culture. For years, people have been using the description “cosy crime” to refer to Christie’s works, especially her Miss Marple mysteries. The image of a dainty white-haired old lady with her knitting and a pot of tea, solving crimes instead of Sudoku seems impossible to dispel.

However, although “fluffy and dithery in appearance”, Christie takes pains to make it clear that Miss Marple is “inwardly as sharp and shrewd as they make them”. She’s someone who knows all there is to know about jealousy, greed and hatred. I’m not the first person to suggest that the key to Christie’s success lies in her ability to pinpoint truths – and often extremely unpleasant ones at that – about human nature. And the universality of human nature is what Miss Marple, with her quiet proficiency in the ebb and flow of rural life, has spent her life observing. “One does see so much evil in a village,” she murmurs tellingly in The Body in the Library (1942).

This brings us to one of the most important elements of Knives Out. It might well fall back on traditional murder mystery tropes, but the particulars of the story couldn’t resonate more truthfully. There’s a biting contemporary political agenda bound up in its comedy stylings. I’m not just talking about the inclusion of the neo-Nazi grandson, nor the fight various family members end up embroiled in one evening about whether Trump’s border policy is sadistic or not.

Johnson cleverly uses the structure of the whodunit to examine what happens when a rich, white family suddenly finds their power and privilege under threat. The more we learn about each of the family, the more we see them for the money-grasping, morally dubious fakes they really are, specifically when it comes to their treatment of Thrombey’s nurse, Marta (Ana de Armas), whom Blanc quickly engages to help him with his enquiries.

She’s practically “one of the family”, everyone is quick to explain, but the reality, of course, couldn’t be further from the truth, evidenced by the fact that, when asked, each and every family member names a different Spanish-speaking Central American country as her homeland, not to mention the countless times she’s reassured by various family members that, if it had been up to them alone, she’d definitely have been invited to Thrombey’s funeral.

That Marta’s mother is an undocumented immigrant who faces deportation if her daughter finds herself caught up in the police investigation is something the entitled Thrombey heirs quickly try to weaponise in their favour. Johnson allows us to laugh at the family’s avaricious phoniness, while at the same time acknowledging the all to real threat they pose to characters like Marta and her mother. It’s equal parts hilarious and horrifying.

While it would be a stretch to describe Christie’s works as quite so politically engaged, it would be foolish to see her novels as completely set apart from the broader social, political and historical contexts in which they were written and set. Indeed, when it comes to the acclaimed screenwriter Sarah Phelps’ recent BBC adaptations – which, over the past few years, have become a stalwart of the Christmas TV schedule in Britain – these contexts have been absolutely central to her vision.

Phelps has spoken often about wanting to rescue Christie’s “cosy” image, allowing the darker side of the novels to shine through. When it was announced earlier this year that the final of her five adaptations will be the 1960s-set The Pale Horse, Phelps explained that, as far back as when she was working on the very first, And Then There Was None (2015), she heard “a little voice in my head saying that I could write a quintet and cover 50 years of the tumultuous blood-soaked 20th century within the genre of the murder mystery”.

Situating her adaptations in the time periods in which the original novels were set is an integral part of this; Phelps wants the weight of the darker elements of 20th century history to hang heavily on the stories.

Take And Then There Were None, for example, a story Phelps described as “genuinely terrifying… nobody is coming to save you… no dapper Belgium detective, no twinkly-eyed and steely spinster is going to arrive and unravel it”.

That Christie wrote the story in 1939, only months before the Second World War was declared, was, Phelps felt, key to the disturbing portrait of psychosis in its pages. The characters, she perceptively argued, “are products of the First World War, of that madness… and the loss of status – the posturings of empire are over and they are the last gasp of it”.

And last year, in The ABC Murders, she introduced viewers to a more maudlin, melancholy Poirot (John Malkovich) than we’d ever seen before; a far cry from the dapper, rotund and rather comically neurotic figure made famous by David Suchet in the famous ITV adaptations that ran from the late 1980s to 2013. So too, Phelps infused the broader story – which was originally written in 1936 – with dark political undertones, inviting her viewers to draw informative parallels between the rise of fascism across Europe in the 1930s and the xenophobia and racism running riot in Brexit Britain today. One mustn’t forget, of course, that despite making his way into the heart of the English establishment, Poirot himself is an immigrant who originally arrived in the country as a refugee. “Having been this celebrated Belgium detective,” Phelps explained to the Telegraph last December, “suddenly, being from another country is not a good thing to be. It taps into now. It’s genuinely chilling how similar it is.”

This supposed politicisation of their cosy crime story inevitably had some viewers up in arms, but return to Christie’s original books, and you’ll find plenty of characters – both those who find themselves in need of Poirot’s services, as well as suspects in his investigations – being at best snippy, and at worst downright rude, about having to answer to a meddling “foreigner”. It’s not, then, that these elements were absent from Christie’s original novels; they just weren’t as pronounced as Phelps has chosen to make them. Indeed, even Christie’s own great-grandson, James Pritchard, has praised the screenwriter for helping him appreciate a new element of his great-grandmother’s works. “I now read it differently,” he told the Radio Times in an interview at the end of last year.

What, precisely, is the enduring appeal of Agatha Christie? This is a question that’s asked so often it’s become as predictable as the inevitable arrival of a new adaptation of one of her novels. The answer is a simple one: she’s both a master plotter, and the sharpest of observers of the dark side of human nature. What’s more interesting right now though is the fact that both Johnson and Phelps have found their own cunning ways of upending this genre, of turning what’s staid and familiar – whether it’s the traditional murder mystery structure, or a classic story or character – into something both contemporary and unexpected. Perhaps this shouldn’t surprise us, though. After all, they learnt from the very best.

This story was first published by Tortoise, a different type of newsroom dedicated to a slower, wiser news. Try Tortoise for a month for free at www.tortoisemedia.com/activate/tne-guest and use the code TNEGUEST.