MICHAEL WHITE discusses how populism has taken over the agenda across Europe.

Sitting down to write this article I left BBC Radio 4 on in the background. Always a mistake, it’s often worse than Google or Twitter in taking over good intentions. Start the Week was marking this week’s 75th anniversary of the RAF’s brutal fire-bombing of the beautiful German city of Dresden – ‘Florence on the Elbe’ – in the closing stages of the Second World War. No, I don’t propose to write about the past, but about leadership. Alas, Europe’s past is always about its present and future too, leaders included. Just look at the Irish election result.

Big picture first. The predictable fall of Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (AKK), Angela Merkel’s chosen successor as German chancellor, means that the leadership of the EU is again thrown into question at a critical time. It comes when the new Commission’s budget crisis, its ambitious climate change agenda, its unresolved immigration policy – the 27’s future relationship with the ‘third country’ UK too, of course – cry out for direction from Berlin, long the sheet anchor of the system. Emmanuel Macron is ambitious to lead, but Paris lacks the heft and Macron is under siege at home.

Authoritarian China, the emerging global power, is turned inwards grappling with the coronavirus epidemic which looks set to ravage the wider world’s health and economy. Russian leadership is negative and disruptive. Most painful of all, the United States is also now in the clutches of a dangerous disruptor, emboldened by his ‘acquittal’ by a rigged senatorial jury, the political opposition weakened by its own ineptitude, not just in Iowa. Under the unruly, incoherent populism of Boris Johnson, Britain does not feel so very different. Dresden’s history should remind us of the fragility of our civilisation.

Even under the communist GDR regime the Saxony capital maintained its long tradition as a high tech as well as cultural centre – from porcelain to cameras – and much money has been spent restoring both since unification in 1990. But cash and a proud culture are no defence. Just as it was an enthusiastic centre of Nazi savagery – from book-burning to the persecution of Jews and artists – so Dresden has since become a nest of neo-Nazi sentiment. Birthplace of the anti-immigrant Pegida movement in 2014, it is also a stronghold of the AfD party. Faced with weekly anti-migrant rallies in the city – its mainstream parties on the council declared a ‘Nazi emergency’ in 2019.

That did not stop the surge. After this month’s regional elections in neighbouring Thuringia a pro-business, centrist, Free Democrat candidate was elected to be minister-president with the votes of AfD deputies as well as some of Angela Merkel’s local Christian Democratic (CDU) team. That broke a post-war convention between the main parties, the CDU and Social Democrats, now in flagging coalition in Berlin, not to deal with far-right parties. German courts have deemed the AfD to be one. Chancellor Merkel hit the roof and the deal collapsed amid resignations, culminating in AKK’s. The saga isn’t over and Merkel’s power to dominate events – and her own succession – is fading.

Sounds familiar? It should.

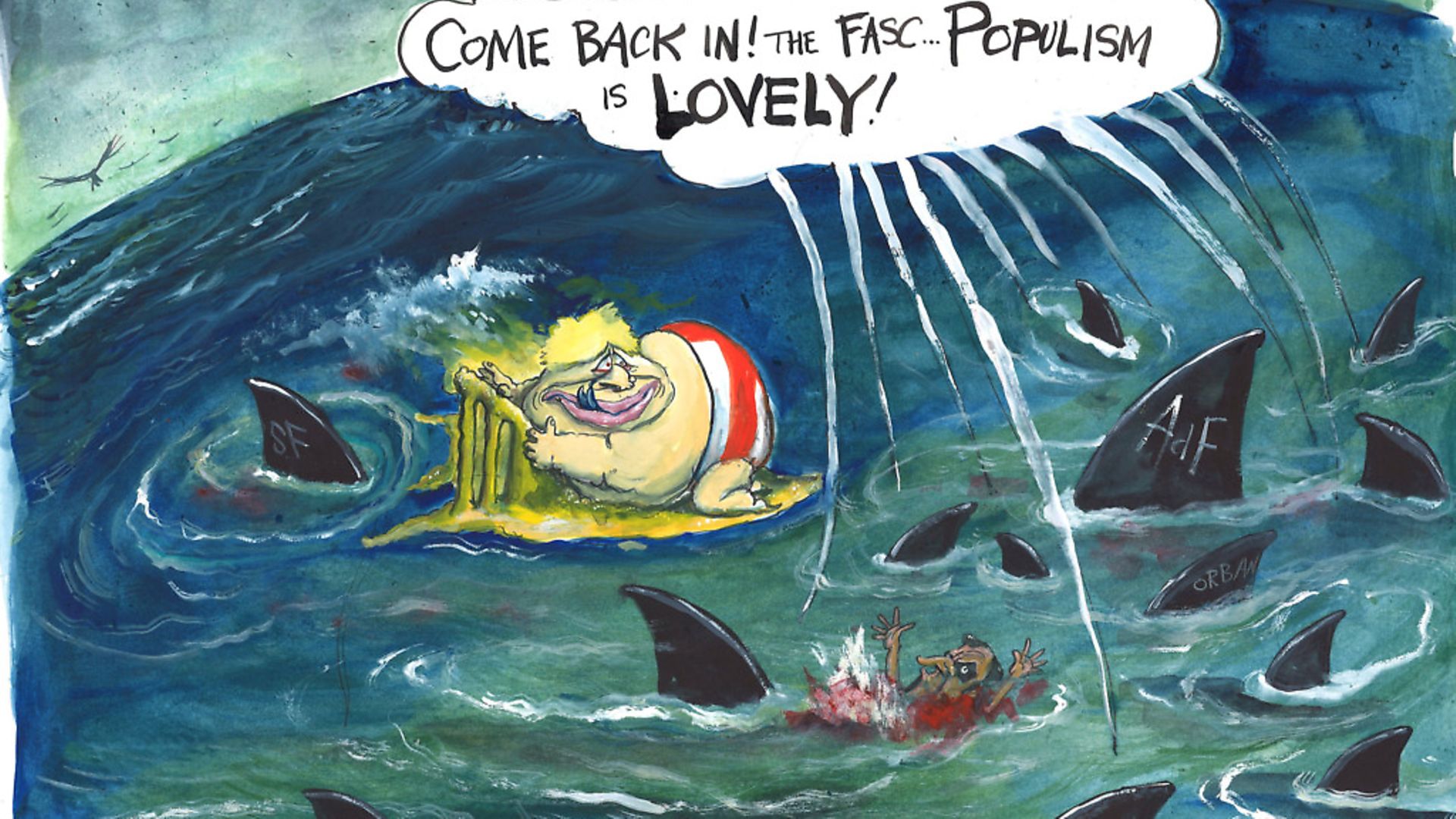

Everywhere we look the once-solid foundations of the post-war order are under attack. More than a decade after the financial crash the mainstream is still not providing answers which will persuade disaffected voters that their protest votes for populists – nominally left as well as right – are a faster road to disillusionment (and worse) than they can yet grasp. When populism fails it can only ratchet up the dial and offer more populism. Things can quickly get ugly. Just look at Donald Trump’s brazen, bullying behaviour since the senate gave him the all-clear.

The latest example of disruption, so conspicuously under our nose that even insular Fleet Street has noticed, is Sinn Fein (SF)’s unexpected – even by itself – success in winning the popular vote (25%) in Ireland’s general election. It helps that the Irish speak English, I suppose. But not even Jason Walsh’s lively report in last week’s TNE expected it to happen in still-conservative Ireland. Whatever Fine Gael’s (outgoing?) Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, has been saying since Saturday’s upset about not dealing with the gunmens’ proxies, a three-way split in the Dail is hard to ignore. Everyone knows that something emerging from its tortuous single transferable voting (STV) system is going to have to give. Fianna Fail leader, Micheál Martin, who condemned SF’s “omerta” towards the IRA only last week, may soon be the man to give it.

It is egotistical of Brits to see Brexit as the driver of this political – possibly constitutional – upheaval, though Brexit played a part. Preoccupied with the issue and EU27 solidarity since taking office in 2017, the relatively inexperienced Varadkar took his eye off domestic issues. Among young voters – Ireland is a demographically young country – and the “left behinds” – often the same people – high rents and housing shortages (just a decade after a crazy housing boom bust Irish banks) was voters’ number one concern. Not far behind was a flagging health care.

Bustling Dublin and the middle class have recovered from the bankers’ crash. Purporting to be a party of the left and belatedly pro-EU, SF tapped into resentment of inequality. It is a debate that sounds very Dresden, which has been part-colonised by West German Wessies to the frustration of left behind and patronised locals who feel Ostalgie for the all-encompassing social network of the old GDR, its youth clubs and day care more than its secret police. AfD revisionists have even tapped into a “bombing holocaust” which tries to equate the RAF with Auschwitz.

But, if twentysomething German voters have no memory of the Stasi, what do their Irish counterparts know or care about the Troubles which all-but-ended in the 1994 ceasefire, before most of them were born? Should socially progressive young Ireland wonder about allegations that former Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams protected his paedophile brother, Liam? Apparently not, historic abuse cover-ups apply only to priests and the ‘elite’. Haven’t the party been power-sharing at Stormont for years? Isn’t SF’s new president and aspiring Taoiseach, Mary Lou McDonald, a Trinity College Eng. Lit. graduate and wholesome mother of two?

All true, but breakaway IRA men tried to bomb a Brexit night ferry on January 31 and Sinn Fein continued to justify an historic IRA murder (the victim was involved in “drugs and criminality”) during the recent campaign. Kevin Toolis, who wrote Rebel Hearts, a gripping account of the Provisional IRA, claimed this week that McDonald is just a brand-cleansing “poster girl” for the Provos shadowy Army Council which still pulls SF’s strings and makes no apology for its past. It sounds a bit like the sentimentalised brutality of BBC TV’s Peaky Blinders.

Whatever Dublin insiders in politics and the media say to dismiss the party’s demand for an all-Irish border poll within five years as their price for cooperation, it is now more firmly on the agenda than a week ago. Johnson’s EU withdrawal deal which leaves Northern Ireland effectively inside the single market – the border down the Irish Sea – is working to further integrate Ireland economically. In the 1921 split, Belfast was the industrial powerhouse. The high tech boot is now on Dublin’s foot.

See what odds on a united Ireland you can get at Ladbroke’s. The paradox of Nicola Sturgeon’s renewed demands for another Scottish referendum is that – at a practical level – Brexit makes an independent Scotland economically much harder, as does the SNP’s increasingly threadbare record after 13 inglorious years in power at Holyrood. For the pro-EU majority in Northern Ireland – also feeling thwarted by Brexit – the logic increasingly works the other way, even if many in the 26 county south don’t want the burden of Unionist dissent.

All that is another way of saying that, at a time of acute geo-political challenge, governance over the British Isles lies in thrall to competing visions of nationalism – Irish, Scottish and English, the latter dressed up as Global Britain, but English and parochial for many. No amount of Boris pipedreams about building a £20 billion bridge across 28 miles of stormy water between Larne and Portpatrick in Scotland – the route strewn with old explosive dumps, as with Boris Airport in the Thames – can disguise the centrifugal danger. Which side would the customs posts be built, prime minister? Michael Gove has just admitted there won’t be “frictionless trade” at Dover either.

Typical of the Johnson era, Tuesday’s controversial announcement that HS2 – the ‘Adonis Line’? – will go ahead over Johnson’s instincts (did Tory donors in the construction industry clinch it?) involved a headline distraction or two: the Irish bridge and a promised £5bn over five years to improve out-of-London bus (and even bike) services. More buses? Excellent, but where’s the money coming from when few now dispute that Brexit will cause a hit to the economy – “only temporary” – and thus to tax revenues? Good question, but I am told that, when Boris unveiled last week’s gimmick – I mean strategic policy statement – on getting rid of “dirty” cars by 2035, officials were specifically told not to produce costings on the cash or carbon.

Even Corbyn Labour made a figleaf attempt to cost its over-reaching ambitions. But that is not how government-by-column works. Ministers have promised to solve the crisis in elderly care. Ker-ching on the till. They want to keep more serious offenders – not just unreformed teenage jihadis – in prison, but have built few of the costly extra prison places promised to house them. Ker-ching again. They want to build more houses and flats, not with Grenfell cladding, and all that infrastructure in “red wall” areas. Not to mention recruit 20,000 more police which won’t be easy even if the pay is improved. Public confidence in poor clear-up rates has dived. Ker-ching, Ker-ching.

It feels a different Treasury than the one the new Lord Spreadsheet – formerly Phil Hammond – ran, though officials there are fighting a rearguard action against the Magic Money Tree economics of Dominic Cummings and other “unelected, unaccountable bureaucrats” as we might call the Johnson kitchen cabinet if it was European. After a Times report that he is losing more turf wars than he wins – HS2 being only one example – the People’s Dom boasted elsewhere in the paper that he’s taking back control of NHS England from its formidable CEO, Simon Stevens. A bad idea and we’ll believe it if it happens. Stevens is a much better politician than Dom and a pal of Dom’s boss at Balliol College, Oxford. Dom has reportedly managed to fall out with First Girlfriend, Carrie Symonds. Not wise.

All of which frames Sajid Javid’s March 11 budget, a fact that keeps him in his job through the reshuffle. Not even Dom the Disrupter dare push the chancellor under the bus this month as the Sun disposed of Holyrood’s finance minister and Sturgeon’s tipped successor. Derek Mackay quit on his budget day for deplorable private behaviour towards a 16-year-old adolescent – or voter, as the SNP usually calls them.

It is no surprise to New European readers, though clearly a shock to those at the Mail and Daily Borisgraph, that a government that wants to spend more must either cut spending elsewhere or raise taxes and borrowing. As Sunday Times economics pundit David Smith wittily puts it, ones that want “to increase spending and cut taxes have to borrow even more.” Wriggle as they may, Jeremy Corbyn, Mary Lou McDonald, and arch credit card splurge, Donald Trump, can’t escape this pretty basic fact.

Boris Johnson, who appears to know as much about economics as my cat (the one that got run over), may denounce and even sack the “gloomsters”, along with half his cabinet. But he can’t sack the facts. So his vassal chancellor is scrambling around for projects to cut – benefit claimants who don’t vote much are always a safe target – as well as taxes to raise. Alas, his red wall election strategy means he must risk offending his heartland voters. Revive Vince Cable’s mansions tax on what are mostly not mansions at all? Slash pension tax relief to a fairer model? Renege on that pledge to cut corporation tax and raise the higher rate threshold from £50k to £80k? He’s already done the last two. The Borisgraph is furious.

All of which should be a field day for a competent and focussed opposition. But for the third time in a decade Labour is distracted by a divisive leadership contest which – unlike 1983, 1992 or 1994 – offers no certain prospect of relief if the best candidate wins, as he looks likely to, campaign dirty tricks against him not withstanding. It’s not just us. In Germany, France, Italy and beyond incumbents hang on by their finger tips and the mainstream opposition are enfeebled. The populists – from Berlin to Dublin via Mario Salvini in Rome – are making the running. In Vienna the Greens have just risked a coalition deal to govern with Sebastian Kurz’s hardline OVP.

In Washington, even more than in the Johnson Tory party, the populist wing has captured a major party. In South Africa the familiar combination of economic distress and glib populist remedies are now eating away at the once sacred memory of Nelson Mandela, the ANC liberation hero a puppet for white power, say agitators in the townships. Why is it happening? Where has moderate leadership gone, where are the alternatives that offer difficult choices, not panaceas?

Mainstream failure to address growing inequality has been part of the story since Reagan-Thatcher gave it a big shove in the 1980s. Not everyone turned out to be a winner after all. The prestige of politics suffered further from bad calls on Iraq and bank regulation. It’s also easy – and right – to blame the savagery of unmediated 24/7 social media which so increases the personal cost and political difficulty of rational public dialogue without rancour and hovering violence.

But media abuse, usually from the right, has long been a constant. What’s changed from my experience and perspective are two critical components. One is the relative financial sacrifice which talented people have to make – lawyers are a good example – to enter politics compared with soaring rewards they can obtain in top public sector jobs as well as in business and finance. Why be a cabinet minister for £140k – a weekly pay cheque in Premier League football – and have the tabloids at your door and in your bins?

But the democratisation of leadership procedures is, alas, a factor, I fear, especially when populism and open selection rules hold sway. Who exactly picked Johnson or Corbyn? Who exactly voted in Iowa to promote 38-year-old ‘Mayor Pete’ Buttigieg and 78-year-old Corbynista, senator Bernie Sanders from the Democrats lacklustre pack? Ditto New Hampshire. Is self-funded billionaire Mike Bloomberg really the best the party can do to defeat a self-styled billionaire? Do you feel that sense of hopelessness many Germans felt in the low, dishonest 1930s? On Sunday, Hollywood surprised itself by giving the Best Picture Oscar to South Korea’s Parasite. It’s a dark and bitter satire on inequality – brutally funny but with no answers.