While wealthier newspapers with larger readerships bowed the knee to the prime minister, this proud regional broadsheet refused to toe the line.

Few in academia will profess ignorance of “no-platforming”. This expression of ideological zealotry seeks to restrict debate to orthodoxies with which its supporters sympathise. It restricts freedom of speech upon which, since the Enlightenment, democrats have relied to test ideas and challenge assumptions.

It is a new way of describing the old sin of censorship which, in the UK, has more often been deployed in the interests of reaction than progress. Neville Chamberlain, Britain’s Conservative prime minister between May 1937 and May 1940, deployed it systematically – and sometimes maliciously – in his efforts to appease Hitler.

From the moment Chamberlain entered Downing Street he worked to make the press support his policy of appeasing the dictators. In his book Twilight of Truth: Chamberlain, Appeasement and Manipulation of the Press, Richard Cockett describes how this ideologically committed appeaser curbed the hostility of British newspapers towards Nazi Germany and converted most of them to his cause.

Chamberlain tamed parliamentary lobby journalists through his dedicated press officer, George Steward. Sir Joseph Ball, the chairman of the Conservative Research Department between 1930 and 1939, helped to cajole newspapers into supporting and promoting the prime minister’s approach.

Chamberlain himself maintained close friendships with Geoffrey Dawson, editor of the supremely influential Times, and also with the owners of the Sunday Times, Daily Sketch and Observer. Steward and Ball helped with the mass-market Daily Mail, Daily Express, News Chronicle and Daily Express.

To Chamberlain’s fury, there was one Conservative broadsheet that steadfastly refused to toe the line: the Yorkshire Post. This proud regional broadsheet was not simply aligned with the Conservative interest. It was published by the Yorkshire Conservative Newspaper Company and run to support the political and financial needs of Yorkshire Conservatives. Nevertheless, Arthur Mann, its editor between 1919 and 1939, performed with genius the role of a truly sovereign newspaper editor.

Mann believed fervently in fourth estate theory: his newspaper had a role to play in political society. It must act as a link between public opinion and government. Mann considered it his duty to follow the evidence offered by his reporters, correspondents and columnists.

These included Charles Tower, the paper’s chief leader writer – previously a correspondent in Germany. In Vienna they had LR Murray, who had met eyewitnesses to Hitler’s intolerant belligerence. John Dundas, a recent graduate of Christ Church College, Oxford, who had just completed his studies in Heidelberg, wrote on foreign policy.

His team gave Mann insight. Independence of mind and faith in journalism’s duty to democracy compelled him to advance arguments that infuriated his proprietors and many readers.

Wealthier newspapers with larger readerships bowed the knee to Chamberlain and depicted appeasement as the only realistic option. They portrayed the prime minister as the statesman who would make it work. Mann demurred assertively.

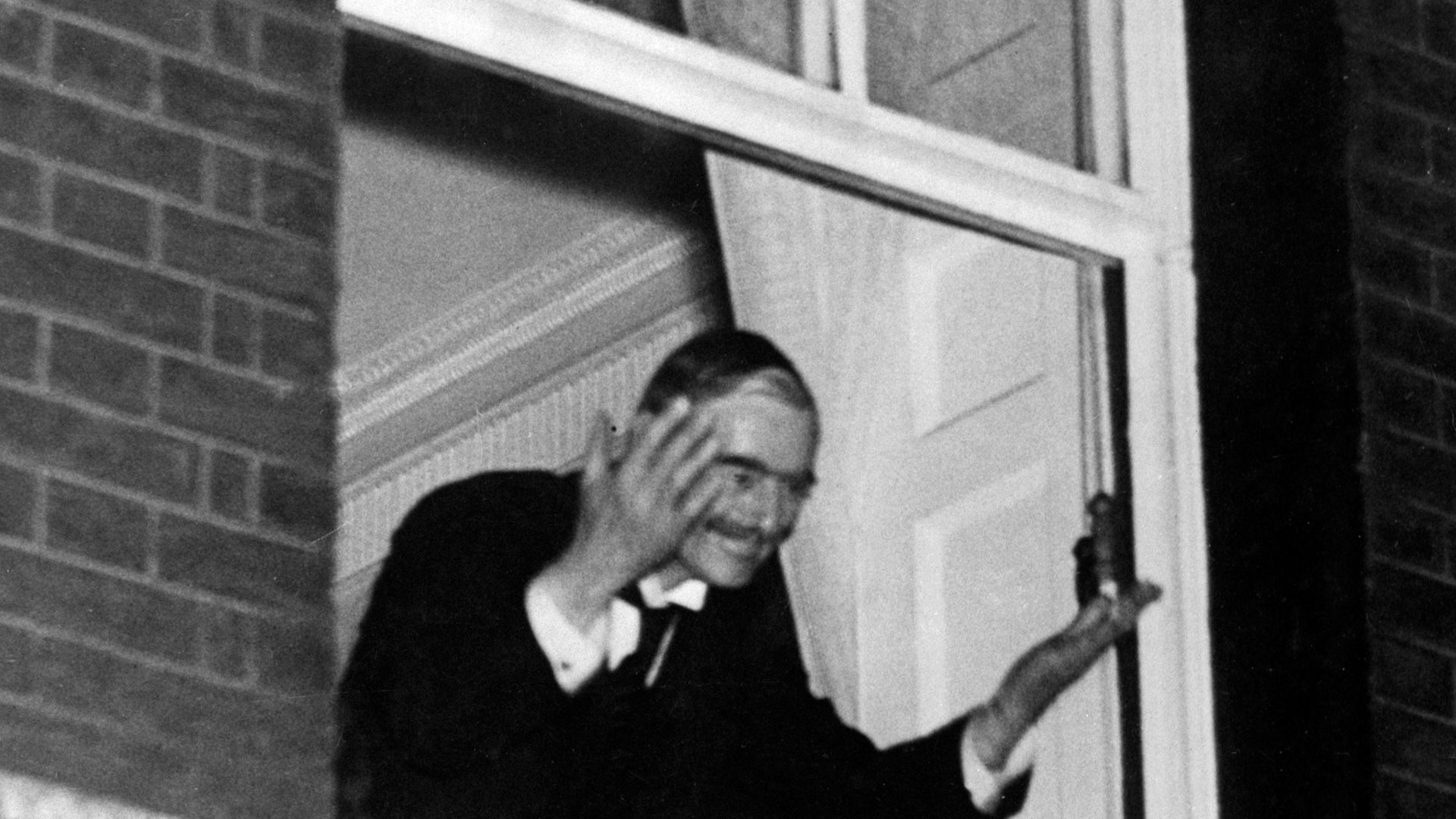

The prime minister and Rupert Beckett, then the chairman of the Yorkshire Conservative Newspaper Association, encouraged Mann to keep his opinions out of his newspaper and support the government. Instead, when the pair met briefly on the morning of March 21 1938, the editor encouraged the prime minister to be robust in his dealings with Hitler. Chamberlain’s response was exquisitely rude. He declined Mann’s advice and exited the room declaring “I’m afraid I have an appointment at 11.15 and it is now 11.14”.

Six months before appeasement’s nadir at the Munich Conference, a Yorkshire Post editorial accused British ministers of harbouring delusions about Nazi Germany.

Noting that “some of the worst Jew-baiters in Germany were even then arriving in Austria”, Mann deployed the Yorkshire Post’s leader column to express his fear that the British cabinet contained men who were “temperamentally unfitted to grasp the realities of the international problem and still less qualified firmly to deal with them”.

As German demands intensified in July 1938, and Hitler reserved the right to treat Czechoslovakia “as a thorn in the side of Germany which the Reich, accordingly, has a right in self-defence to rip out and destroy”, the Yorkshire Post insisted that appeasement was futile. Following the Anglo-French betrayal of Czechoslovakia at Munich in September, the Yorkshire Post described appeasement as “indistinguishable from a surrender to threats”. Its architects had a “tragic lack of conviction”.

Now under intense pressure from his proprietors and accused of endangering the nation and misleading the public, Mann pressed on. An editorial headlined: “Encouragement of Aggression” appeared in the Yorkshire Post on December 8 1938. This condemned Chamberlain’s foreign policy: by surrendering to force, the prime minister had “repeatedly encouraged aggression”.

A prime minister who was “by nature unfitted to deal with Dictators” had ignored advice from experts qualified to advise him. His policy was “threatening the safety of the realm”. It was “likely in the near future to threaten it with danger still greater”.

Newspapers rarely flatter their rivals, but the liberal Manchester Guardian, which agreed with Mann in his stance on appeasement, captured the courage and wisdom of Mann’s Yorkshire Post. It described “soundness of judgement, tenacity of purpose, loyalty to principle” and the courage to be unpopular “and even to offend the Party if the Party were not right”. High praise, but no less than Mann deserved.

He was an heroic editor and a beacon of excellence in journalism. As debates around freedom of speech animate Britain’s universities, we should celebrate the value of dissenting opinions and the courage of those who refuse to be silenced.

Tim Luckhurst is principal of South College, Durham University. This first appeared at theconversation.com