IAN WALKER on what Notre Dame – and Europe’s other cathedrals – truly stand for in the 21st century.

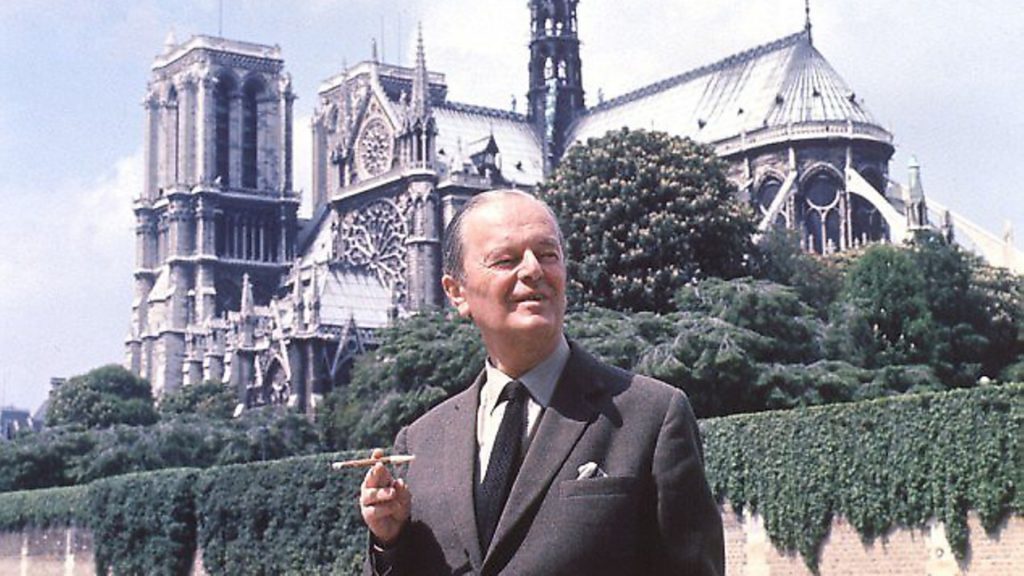

Near the opening of his 1969 television series Civilisation the art historian Kenneth Clark says: ‘What is civilisation? I don’t know. I can’t define it in abstract terms yet, but I think I know it when I see it, and I am looking at it now.’ He was looking at Notre Dame de Paris.

It is even harder to define what is civilisation now than it was half a century ago when Clark made his programme. Intellectual and political concerns about Western elitism and eurocentrism, the pervasive influence of cultural relativism, the horrors of the last century and the spiteful parochialism of populism, have all made a robust defence of Western European civilisation as an inherently good thing problematic. But despite that, it seems to me, that when the world was looking at Notre Dame in flames last week, the horror that millions felt had something to do with this question of civilisation. Something that is both of part of us and which also transcends the brevity of our lives and concerns was on the brink of disappearing. Something that should be permanent suddenly confronted us as being transient.

Clark’s series argued that Western civilisation exists in the permanence of its art, architecture and literature. Its origins lie in Greek and Roman culture, but then, for hundreds of years during what is sometimes erroneously called the Dark Ages, this civilisation almost disappeared. But then, around one millennium ago, it was reborn, and the form that rebirth took was the building of Western Europe’s great Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals.

Putting aside those modern concerns about Western elitism, eurocentrism and cultural relativism it is the case that if we can define civilisation as being the permanence of its art and architecture, then that is obviously true of these medieval cathedrals. From Durham to Salisbury, from Chartres to Cologne, these masterpieces of the medieval imagination still draw thousands upon thousands of visitors each year. They still mean something to us almost 1,000 years after they were built.

But why? Can it still be to do with Christianity? In 2007, the TearFund survey reported that only about 10% of the British population went to church regularly and that figure is now probably lower. In Europe’s Catholic counties it is different – and it was apparent to anyone seeing the gathered crowds singing hymns as they watched Notre Dame in flames that Christianity still holds great sway over parts of the collective French imagination. But, despite that, to argue that Christianity is still at the heart of 21st century France is a bit of a stretch.

But if Christianity doesn’t hold sway over our collective imagination in the way it did in the past, cathedrals still do. They are still part of our civilisation. They still seem to hold meaning for us, even if is just something to gawp at while we are on our holidays. Before the fire, an average of 30,000 people a day visited Notre Dame. These numbers have transformed the ancient centre of Paris into a place of tourists and school parties, of selfies and souvenirs. It’s easy to sneer at that, but having 30,000 people a day gathering to gawp at something ancient and beautiful really isn’t a bad way for the world to be. Paris has seen much, much worse than selfie sticks on the Pont Neuf.

But while it is clear that these buildings mean something to us, trying to get to the bottom of why isn’t always obvious. For some, the reason lies in the Bible – but that doesn’t explain the 30 000 people a day. To try and make sense of that figure maybe we can look to another book, not the Bible, but a secular masterpiece written almost 200 years ago.

When Victor Hugo’s novel Notre-Dame de Paris was translated into English in 1833 by Frederic Shoberl it was retitled The Hunchback of Notre Dame. It was not surprising that Shoberl did this; Quasimodo, the cathedral’s hunchbacked bell ringer, is as vivid a character as any found in literature. With Quasimodo, it was as if Hugo had transmogrified stone into words; that he had written one of the cathedral’s gargoyles into life.

But Hugo disliked the English title because while Quasimodo was a key character in the book’s melodramatic plot, the real star of the novel, if not the very point of the novel, is the cathedral itself.

The novel Notre-Dame de Paris, as well as being a rip-roaring yarn about thieves and gypsies, a wayward priest and grotesques, is a metaphysical treatise on time, imagination and meaning, and the full weight of these themes is found in Hugo’s description of the stones, windows, arches and towers of the cathedral.

The novel makes for quite an odd read if you only know the story from any one of the dozen or so film versions that have been made. The book opens in 1482 at the Epiphany celebrations in Paris. It is typical Victor Hugo fare. Amid big crowd scenes in grand squares and in fierce little dramas played out in Parisian back streets and garrets, many of the key characters are introduced: Gringoire the playwright, Frollo the cathedral archdeacon, Captain Phoebus, Esmerelda the Gypsy, the Truands (the thieves and outcasts of Paris) and Quasimodo himself. In the lives of these people, the story begins to come into focus around those good old themes of death, desire and crime. So far, so good.

And then, about 25 pages into the book – in a section that never made its way into the Disney cartoon – Hugo suddenly stops with the story and instead starts describing Notre Dame in precise detail, not as it was in medieval Paris but as it was during his own time.

He describes how it has fallen into disrepair and how it has been constantly renovated and changed by generation after generation, each with their ‘miserable gewgaws of a day’. Hugo is cross about this but then seems to change his mind about these architectural affronts. He argues that this cathedral – this ‘great edifice’ – is like a mountain, a work of centuries. He argues that time is the architect, the nation is the builder.

Reading on, and anyone bemused by Hugo’s diversion into describing the metaphysical qualities of architecture is in for a second, even odder, diversion. As soon as he stops with this description of stained glass, sculptures, pillars and pudgy cupids he gets stuck into describing Paris as you would have seen it in the 15th century from the top of one of Notre Dame’s towers.

At length, he describes a city of bridges and gates, turrets and spires, roofs and gables and ‘the capricious ravine of streets’ all spiralling out from this cathedral that sits on the island – Île de la Cité – in the middle of the city.

In these two sections, Hugo is making huge claims for the power of fiction and of art. He is placing the book, like the cathedral, at the centre of Paris. But even more than that he is claiming that the book is Paris.

Hugo’s novel is his attempt to transmogrify all stone into words, not just a gargoyle into Quasimodo. He is trying to render the whole of the cathedral – the towers, the flying buttresses, the windows – and the whole of Paris – the roofs and the gables, the alleys and the spires, and all the residents from the king down to the sewer rats – into phrases, sentence and paragraphs.

And right at the centre of all this is the cathedral. Not a palace or a castle or any other site of obvious political power, nor a tavern or a guild or any other place of lowlife intrigue and ambition. It’s the cathedral, it’s this masterpiece of the medieval imagination that Hugo places at the heart of his attempt to recreate Paris. And the reason he does this is because the cathedral is the thing – the art – that Hugo wants to measure his book by.

The 11th and 12th centuries saw a period of relative stability in Europe. The Viking raids stopped and power throughout Western Europe was consolidated into the Capetian dynasty in France, the Hohenstaufen dynasty in Germany, Burgundy and Italy and the Norman dynasty in Normandy and England. Alongside this, Cluniac monasticism gave Christianity a new spiritual and intellectual vigour. As Christianity moved into its second millennium this political stability and religious vigour shaped the aesthetic impulse behind the building of the Romanesque churches and cathedrals.

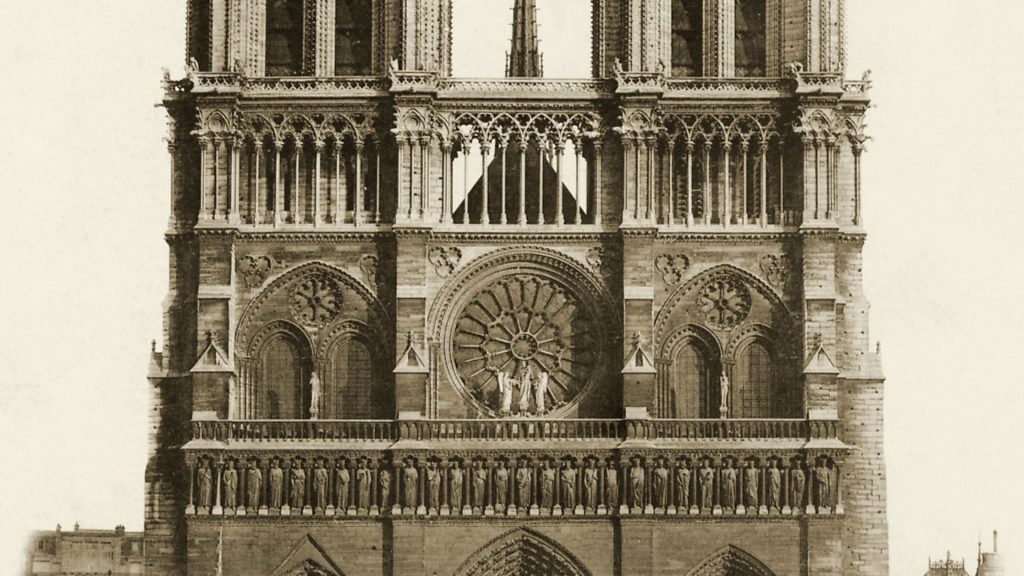

As the name implies, Romanesque architecture looked back to Rome for inspiration. It aspired both in form but also in spirit to the idea of permanence; to the idea of civilisation. Throughout Western Europe, churches and cathedrals were built of solid, heavy stone. Tiered arches and giant pillars carried the weight of huge vaulted ceilings.

These buildings were solid and imposing; they contained within them something of the quality of geology, of the earth itself, in their weight and scale. There are still many extraordinary Romanesque churches and cathedrals in Europe, including in the UK where they are usually described as being Norman.

But if these buildings were to become the solid and permanent basis of what became Western civilisation, what followed – the Gothic – elevated that civilising impulse to build something permanent, to the level of something sublime.

In Paris, some time around 1135, Abbot Suger, the Abbot of St Denis, wanted to rebuild the Basilica of St Denis. The working brief he gave to his masons (who were, in effect, the unknown and unnamed architects of these buildings) was that he wanted the place to be full of light. At this time masons were starting to incorporate architectural and engineering ideas from Armenia and from the Arabic culture. Instead of tiered arches stacked upon each other, they were now able to build single huge arches, which, along with rib vaulting, could carry the full weight of the vaulted ceiling. Even more weight could be held when flying buttresses were added to the outside of the building. These architectural devices meant that the nave that runs through the main vault could now be illuminated by huge windows without the light being blocked by giant pillars.

The Basilica of St Denis is usually regarded at the first extant Gothic building (‘Gothic’ is a misnomer. The style has nothing to do with the Goths). Light floods into the structure and the stone seems to take the properties of everything it isn’t – it seems weightless. For the Christian sensibility this combination of light and stone reproduced the majesty of heaven or God, but a more secular and humanist take on these building is that mankind had built something where the physical laws of light and mass had created something sublime.

The Gothic cathedrals were – are – triumphs of the human imagination. And this was not just at a technical level. In the way they made stone seem light, and light seem eternal. They created meaning and pushed physical law to create something that was both beautiful and which seemed to stretch out beyond us. The construction of these cathedrals involved not just acts of devotion, but also expressions of the unique capacity of humanity to elevate its existence to something beyond itself. Civilisation is not just permanence, civilisation is also imagination.

Notre Dame soon followed the lead of St Denis, and the contest wasn’t entirely to do with aesthetics. St Denis and Notre Dame were rivals in the struggle to be at the centre of religious life in Paris – and the struggle was for cash as much as was to do with souls. These centres of religious life were also centres of commercial life and St Denis and Notre Dame, like shopping centres, were always competing for footfall.

So St Denis’ sublime Gothic redesign that transformed all that architecture was capable of was also a commercial makeover to increase market share – and Notre Dame fought back. The Romanesque cathedral was demolished and a new Gothic one – the one that still stands, albeit in blackened, damaged form – was built to replace it. However, while Notre Dame is a Gothic cathedral (it certainly has traces of the Romanesque) and while it is one of the masterpieces of the medieval imagination, its beauty and power does not come from its purity of form. Architecturally, it is a bit quirky. However, we can safely say, 900 years on, that while St Denis should be a ‘must-see’ on any trip to Paris, it is Notre Dame that won the footfall competition.

But getting back to Victor Hugo’s book, Notre Dame had, in the early 19th century, fallen into a set of disrepair. The secular spirit of revolutionary France and the endless instability of the decades of republicanism, Bonapartism and the Bourbon restoration had left the cathedral in a tatty state.

Hugo wrote the book, in part, to remind Paris that this extraordinary cathedral sat at its heart. And it worked. One of the consequences of the book was that Notre Dame was renovated (as were huge parts of Paris). Much of this restoration work at Notre Dame was carried out by Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc an architect who restored much of France’s medieval buildings (though the first thing he was known to have built was a barricade during the 1830 revolution). Notre Dame’s collapsing spire, that made the front of the world’s newspapers last week, was designed by Viollet-le-duc.

In Hugo’s book, the swirl of human life – that mixture of boredom, desires, appetites, ambitions, industry, thrills and idiocy (and he is one of the great dramatists of all that blather) flows around the cathedral.

And the flow of that blather alters the cathedral; additions are made, things get worn away, damage is done, ropey repairs are carried out. For Hugo, Notre Dame seems to be in a state of permanent flux. But at the same time for Hugo it is also the opposite to all that. It is solid and permanent and fixed.

This is a powerful metaphor, not just for Paris but for our idea of civilisation. Kenneth Clark believed civilisation lies in permanence – but when we see something that should be permanent in flames we are suddenly confronted with the idea that civilisation is also a process of transience; it is fixed and unfixed, immutable and ever-changing, broken and repaired.

And this is why Hugo succeeded in his book being as great as the cathedral itself, which was always his ambition. Both this book and his other masterpiece, Les Misérables, are monolithic in the way they sit in European culture or European civilisation. They are slab-like and solid but yet are also – with the endless adaptations, cartoons and musicals – mutable. ‘Everything is fixed and everything changes’ is at the heart of how Hugo saw the cathedral and how he saw Paris. It’s how his books are.

Western Europe’s glorious medieval cathedrals remind us of this. They seem to have the permanence of physical law, but that status can be delicate. Victor Hugo wanted his book to be as important a part of Paris – and of civilisation – as Notre Dame. In the way, he described the sublime glory of the cathedral and the endless flux of Parisian life he succeeded. Civilisation is permanence and civilisation is imagination.