The UK’s entry into Europe was as much the result of French politics as it was British, argues OLIVIER DUHAMEL. And it was his own father who ensured that it happened.

With Brexit now upon us, let’s look back, and reflect a little about ‘Brentry’.

It is of course well known that the UK’s entry into the European Economic Community (EEC) was not just once, but twice, refused by General de Gaulle.

The first application for membership was made in a letter from Conservative Prime Minister Harold MacMillan to German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard on August 9, 1961, six days after a favourable vote in the House of Commons (313 votes in favour, 4 against, abstention by Labour MPs). It spelled out precisely a wish ‘to open negotiations to accede to the Treaty of Rome’. The Council gave unanimous approval on September 27. It was only during the negotiations that France, and more particularly our president, General de Gaulle, raised numerous objections.

He was helped in this by the exemptions demanded by the British government on the Common Agricultural Policy and the Common External Tariff, two foundation stones of the EEC. And so, on January 14, 1963, at a press conference, de Gaulle made his first veto, which he justified by reference to la singularité britannique.

How interesting it is, today, bombarded as we are by the thoughts of Brexiteers, to compare his analysis of this singularité with their expressions of the same thing. England, said de Gaulle, is insular, maritime, bound by trade and markets often to distant countries, the US, the Commonwealth. The nature, attitudes and structures of Britain, he said, made the Brits ‘profoundly different’ from European mainlanders.

When it was Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s turn to send a letter, dated May 11, 1967, stating more clearly that the UK wished to ‘become a member of the European Economic Community’, de Gaulle’s arguments for his second veto were subtly different.

British insularity, yes, the Commonwealth, certainly, but this time with a greater focus on the special ties binding the United Kingdom to the United States. De Gaulle’s position is at once pro-European and Gaullist with regards to sovereignty. Pro-European because he does not want Europe to be reduced to a free trade area, forced to accept exceptions to its common policies. Gaullist and suffused with the importance of sovereignty, because he was determined to preserve the national character of French defence policy in particular.

Two years later, everything changed.

Recall the chronology: July 1970, reopening of the accession negotiations; successive reading by the Commons of the law of accession, a motion approving the principle passed by 356 votes to 244; second reading in February 1972, 309 for, 301 against; definitive adoption on July 13, 301 for 284 against; entry into the EEC January 1, 1973; Labour victories in the elections of February then October 1974; respect for the commitment made to give the decision to the people.

On June 5, 1975, two-thirds of voters voted (65%) and more than two-thirds of them voted ‘yes’ (67%). No 52%-48% close run thing back then. Interesting too that the English were most solidly in favour (69%) followed by the Welsh (65%), the Scots (58%), and, some way back, the Northern Irish (52%). How times change.

Again, much of this is well known. Much less well known, however, is the factor that led to the reasons for the lifting of the French veto, which thus allowed UK membership – Brentry as we might call it – to take place. That factor is all about French political life, not British, and more precisely it relates to the election of General de Gaulle’s successor, Georges Pompidou. Here, another referendum enters the story.

De Gaulle called a referendum on plans to reform the regions and the Senate. All very arcane, very French, of little interest across the Channel. But on April 27, 1969, de Gaulle lost that referendum. He took responsibility for the defeat. The president of the Senate, Alain Poher, a centrist who had been very engaged in the winning ‘no’ campaign, became acting president of the Republic. He decided to run for the top job. In the early polling, he was ahead of Pompidou, de Gaulle’s former prime minister, and predicted to be the winner. Pompidou needed support from the centre.

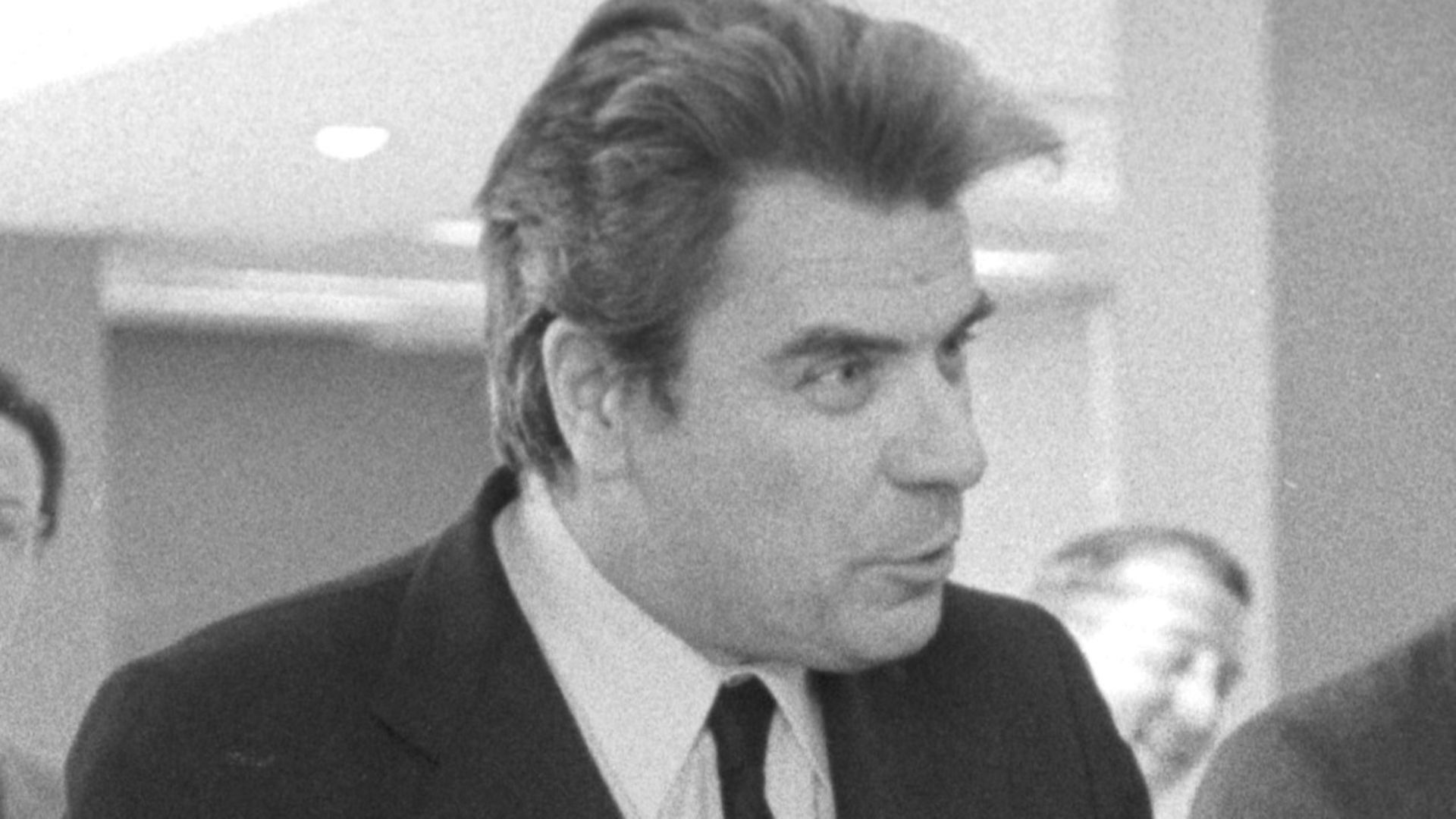

At the time, the centrist opposition group in the National Assembly was chaired by Jacques Duhamel. If I know this story well, it is because he was my father. By rights, given where they were on the political spectrum, he would be expected to support Poher. But he thought his election would be damaging, and plunge France back into the machinations of the Fourth Republic. Yet when it came to the question of supporting Pompidou, he could only do so on the basis of demanding and obtaining certain concessions.

At midnight, April 27, de Gaulle resigned. Hours later, Georges Pompidou and Jacques Duhamel met in secret over breakfast in the apartment of a mutual friend, a business leader called Françis Fabre, in rue de Grenelle, not far from the National Assembly.

My father put forward two conditions as the basis for his support for him. The first was easily met: it was to set out plans for a less authoritarian exercise of power, less focused on the individual who became president, more centred on the development of civil liberties.

This was not unimportant, but vague enough for Pompidou to be able to accept it. The second condition was significantly more weighty. Duhamel demanded the lifting of France’s veto preventing the UK’s entry into the EEC. Pompidou reflected a little, and then agreed.

And that, readers of The New European, is how a major turning point was born in the history of the old Europeans, and what is now called the European Union.

We will never know if Pompidou, though certainly less rigid and nationalist than de Gaulle, would have reached this point by himself. But what is certain is that he did it, at the time that he did it, not out of any great vision for Europe, or any great friendship with the UK, but to obtain the support of Jacques Duhamel and to give himself a better chance of being elected president.

How often does history go like this – decisions of huge importance, changing the future of a country and a continent, made for immediate political reasons. Plus ca change, we might say, looking at British politicians now.

With Pompidou installed as president, in forming his first government, he had to include centrists of the small party founded by Jacques Duhamel, the CDP (Centre, Democracy and Progress). It was widely expected, not least by Pompidou, that Michel Debré, historically as Gaullist as they come, would be Minister of Foreign Affairs.

That was a red line for Duhamel. He told Pompidou that if Debré was appointed, he would not participate in the government. He refused point blank that someone so defined by sovereignty should be in charge at the French foreign ministry, the Quai d’Orsay. Once more, Pompidou yielded, Debré was made Minister of Defence instead, and the door was opened for the UK’s entry.

De Gaulle and Pompidou apart, I doubt these names of past French politicians mean that much to either you, readers, or indeed to the British politicians now trying to make sense of the vote on June 23, 2016 to leave the EU. Yet they were a major part of the story now so dominant in British politics and the development of British history. The great irony to ponder, however, is that the Gaullists opposed Brentry because of their fear it would weaken Europe, reduce it to a large market, overly subject to the interests and habits of the United States.

The pro-Europeans, on the other hand, actively wanted Brentry, and saw it as the way to strengthen Europe. Some of those arguments are still live today, but as the UK prepares to leave, there is perhaps a consensus developing on the European mainland that the UK came in, then acted more as a brake than a driver of the European project.

Olivier Duhamel is professor emeritus in public law, president of the National Foundation of Sciences Po (Sciences Po). He has just published, with Laurent Bigorgne and Alice Baudry, Macron, et en même temps…, (éditions Plon)