Many Remain voters have expressed frustration at the lack of an electoral pact between pro-EU parties. Barnaby Towns argues they need not worry.

As we prepare for European elections the government said would never happen, support for the UK’s EU membership is at record highs. Remain is backed by 58% of voters compared to 42% for Leave, the latest ComRes poll finds. This lead is a 10% swing from the referendum result three years ago – higher than for any general election since 1997.

Remain stands at 61% compared to the government’s Withdrawal Agreement and 57% against no-deal, YouGov finds. And more than half back a new referendum, versus about a quarter each who either oppose or don’t know, BMG research reveals.

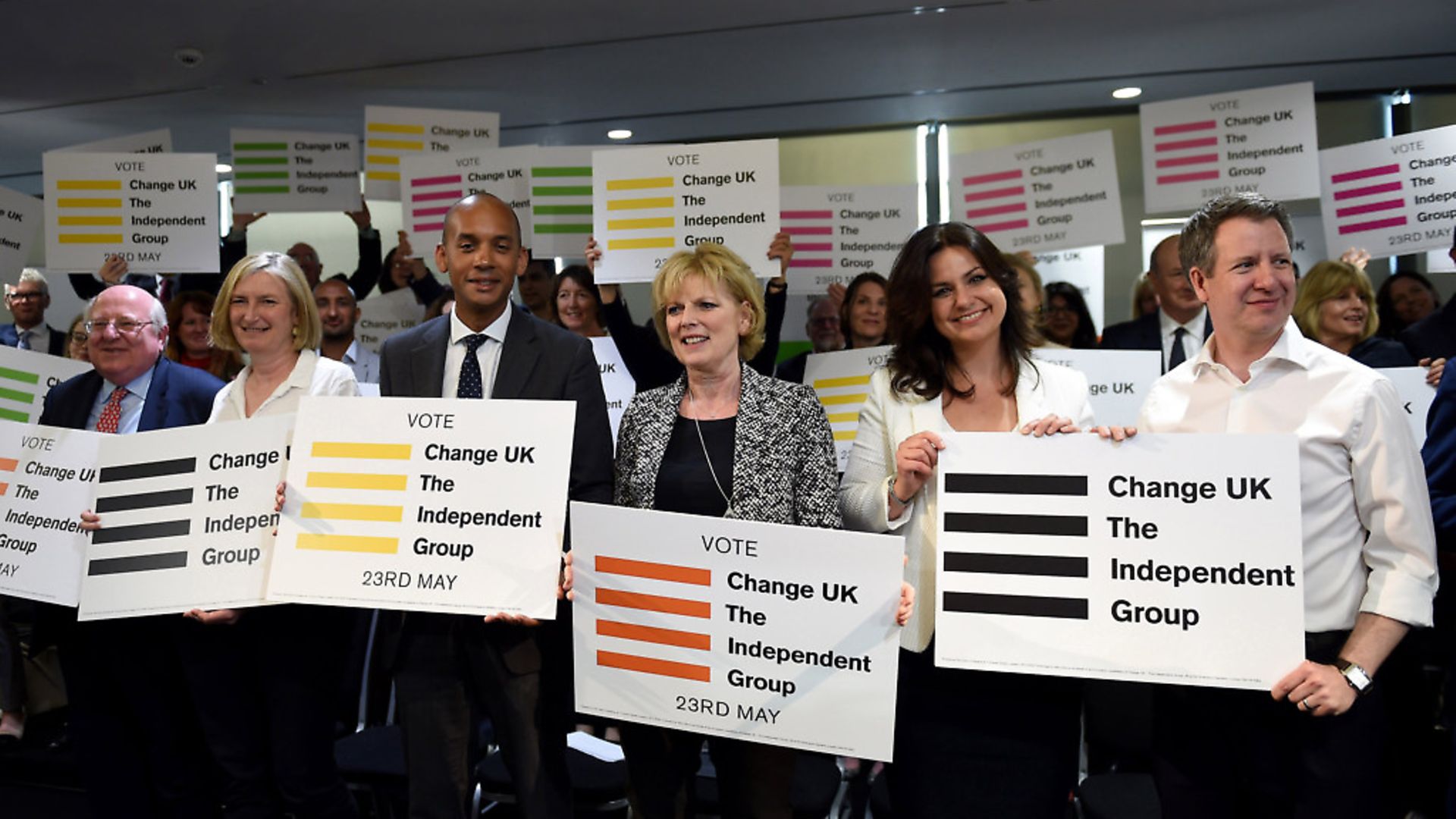

Despite these majorities and this momentum, some Remainers fret that the lack of an electoral pact between newly-minted Change UK and the Liberal Democrats, the Green Party, the Scottish Nationalists and Plaid Cymru will harm the pro-European cause by splitting the Remain vote and European parliament seats. But electoral facts don’t support this interpretation.

In this election, a single-candidate slate requires the creation of a new party with its own unified donations and election spending reporting – hard enough even without the short notice – or each party selectively standing down in nations and regions, backing one option.

Presumably, this would mean the SNP in Scotland; Plaid in Wales; and Change UK, the Lib Dems and Greens taking three English regions each. But even if this carve-up was practical, it wouldn’t make much sense.

For starters, is it really smart for unionist parties to stand aside in Scotland and Wales in deference to separatists? Moreover, Change UK is a new party testing its offer for the first time. The Lib Dems and Greens are established parties, but in England both do better in the south than the north and have only one MEP each in the south west and south east, respectively – the same regions as Change UK’s MEP defectors.

And this election is not really about seats. MEP numbers are determined by population share, so the UK elects only 73 of 751 MEPs: 10% of the total. And while the European parliament must approve any Withdrawal Agreement by majority vote, the EU Council calls the shots – for instance over the extension – while the Commission is the EU’s negotiator.

Two-dozen scandal-prone Brexiteer freeloaders elected under UKIP’s banner in 2014, and perhaps again under Britain’s perennial populist in 2019, irritate but are irrelevant.

Then there is the unprecedented focus on the electoral system used to elect the UK’s MEPs since 1999. Named for Belgian mathematician Victor d’Hondt’s 1878 method, constituencies of varying size – electing as many as 10 MEPs in the south east and as few as three in the north east – award each seat to parties from a numbered list of candidates. The party with the most votes is awarded the first seat; their vote is then halved to reflect this. The party with the next most votes receives the second seat, their vote is then halved and so on until all seats are allocated.

In practice, this system favours larger parties, especially in regions with few seats. In 2014, the lowest winning vote share for any party in the south east was 8% but in the north east it was 18.3%.

The ‘single transferable vote’, invented by Brit Thomas Hare, popularised by John Stuart Mill in an 1861 essay, used in Northern Ireland, and backed by the Electoral Reform Society, which allows voters to rank candidates is more proportional – an idea for 2024, perhaps, if we remain.

No less importantly, Change UK, Lib Dem, Green, SNP and Plaid voters aren’t interchangeable. There are differences beyond unionists not wanting to vote for separatists: Greens have a radical economic agenda not shared by many non-Greens; both Greens and Lib Dems harbour small Brexiteer minorities, whereas Change UK is entirely pro-Remain; and Change UK uniquely unites Britain’s social democratic and one nation conservative traditions.

Cooperation is happening. Candidates from the pro-EU Renew Party are standing under Change UK’s banner and all five pro-European parties work together in the People’s Vote campaign with Labour and Tory allies. This year, the pro-EU five could well out-poll the two no-deal outfits, while Labour tries to face both ways and Tories nominally back May’s hard Brexit plan.

The Europhile vote, not evenly spread nationally like the traditional centrist vote, but concentrated among young, university-educated and urban voters, could become a real power in the land. After all, Remain is now the majority.