In the most unlikely place, PATRICK SAWER finds a poignant family link to Italy’s fascist past and a reminder that this dark chapter of the country’s history is not yet closed.

There’s a spoon in my kitchen drawer that holds a dark secret and it’s a secret shared by many families in what is now modern, democratic, beloved, benighted, beautiful Italy.

In itself it’s quite an eye-catching item, its pointed head like that of a spear, its handle curving and tapering at the edges. A piece of everyday modernist design for the home.

But this is a fascist spoon and its story runs like a black thread though a country that has, once again, found itself haunted by the ghosts of the past.

There is nothing intrinsically political about a spoon of course. A spoon is a spoon is a knife and fork. But this one has its provenance and its political pedigree stamped on the back, in still clearly visible lettering: Fasci Italiani all’Estero.

The Fasci Italiani all’Estero (‘Italian Fascist League Overseas’) was the international wing of Benito Mussolini’s thuggish National Fascist Party, set up in the 1920s to promote his regime across the globe, particularly in those countries where Italians had emigrated in such large numbers from the mid-19th century.

Its task was to report on anti-fascist exiles, counter the influence and success of Italian trade unionists in countries such as the United States, Argentina, Belgium and Australia, and act as a mouthpiece for the regime in Rome.

The organisation, which in 1929 claimed more than 100,000 members, was also active in the Italian colonies of north Africa, which Mussolini vaingloriously dreamt would form the basis for a new Roman Empire. His dreams of course came at a dreadful cost to the inhabitants of what would later become modern-day Libya, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia.

Thousands of these aluminium spoons must have been produced and distributed during the 1920s and 1930s, as Mussolini tightened his grip on every aspect of life on the Italian peninsula, before embarking on a disastrous war as the unequal ally of Hitler’s Germany.

Which brings us back to how this particular spoon came to be in my family’s drawer. It was, in all likelihood, issued to my maternal grandfather, Giusto Nicosia, while he was working as lorry driver, shifting goods across Italy’s African colonies shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War.

He was eventually captured by the British, who, as the Italian Army fell back across north Africa, interned him in a detention camp as a civilian prisoner of war. He retained fond memories of his English captors as humane, dignified and above all ‘correct’ and was delighted when his only daughter later decided to marry an Oxford-educated Englishman: my father.

But Nonno was no fascist pioneer of Mussolini’s doomed African adventures. The reason he wound up in Africa was because he had participated in an action deemed subversive by the regime.

Sometime during the mid 1930s, Giusto, who then worked on the Italian railways, took part in a strike in demand of better pay and working conditions. He was not particularly militant – and not known to have been an activist or supporter of the now outlawed Communist or Socialist parties. He was a committed Catholic and would indeed go on to be a supporter of the Christian Democrats following the birth of the Italian Republic at end of the war, as would most of his other children.

But his colleagues had voted in favour of industrial action and Nonno decided to abide by their democratic decision. That was enough to get many of them, including my grandfather, sacked and blacklisted by the fascist authorities,

With little prospect of returning to the railways, or any other relatively well paid state employment, while Mussolini was still in power, he took the decision to leave behind his wife Maria-Antonietta and children in Rome and try to make a living overseas, in Italy’s African colonies.

The obvious point of my grandfather’s story, and that of the spoon he picked up in Africa, is that not every Italian family shared the ideology of fascism – though many, many did, for all their protestations following the end of the war and the birth of the new democratic republic – but that Mussolini’s totalitarian regime so inserted itself into the home that even domestic items bore its stamp.

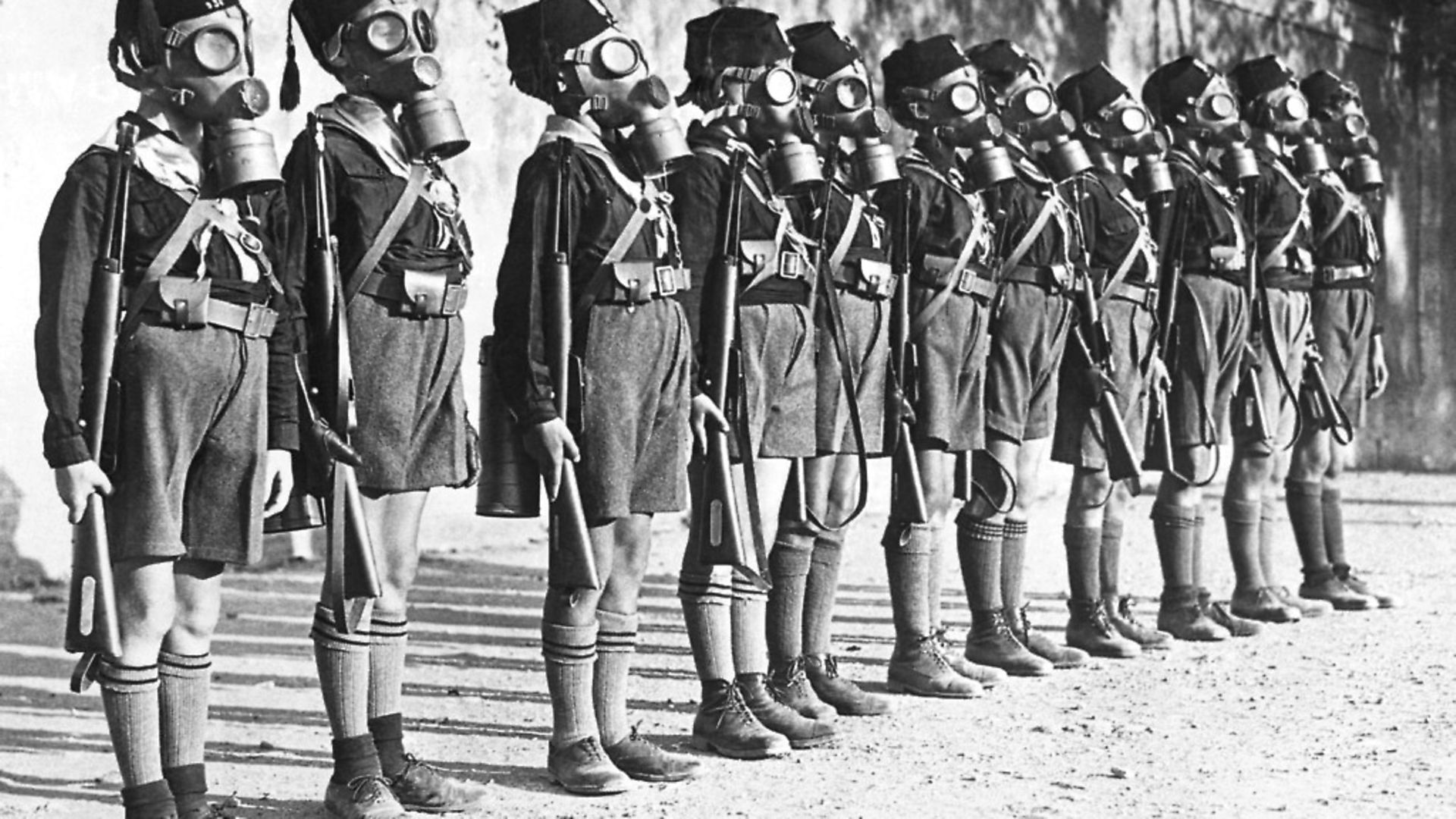

Similarly, many an Italian family album of a certain age will contain what long fascinated me as a child; photographs of children my age in serried rank, strutting across a parade or playground in para-military costume.

These were the Balilla, the Fascist Party’s youth wing – named in honour of the boy reputed to have started the revolt against the Austrian forces occupying Genoa in 1746 – and, like the Hitler Youth, every child was obliged to take part.

One was the young boy who grew up to become one of my favourite uncles, and whose puffed out chest and jutted chin, in imitation of Il Duce’s peacock pose, stared out at me in black and white from the pages of my mother’s teenage photograph album.

Go on holiday to Italy and the remnants of its fascist past are there before your eyes. They include the marble statues of classical sporting heroes, the prototype of new fascist man, which still line the sports complex where I learnt to swim at Mussolini’s Foro Italico in Rome – his imitation of the ancient forum.

The architecture of Fascism also dominates the new town of Carbonia in Sardinia, built in 1938 to provide homes for the miners of the nearby coalfield.

Also still evident, and more welcome, are the symbols of the long, redemptive, struggle against fascism and the Nazi occupiers who took over following Mussolini’s downfall in July 1943, whether in the street corner plaques to resistance fighters executed or lost in battle, or the resistance songs still sung at left wing gatherings.

One example, which might surprise even those familiar with the history of the war ofliberation fought across central and northern Italy by the resistance bands in the torrid 18 months between the surrender of the Italian Army and the arrival of the Allies, illuminates this proud progressive tradition.

Alessandro Sinigaglia was black, he was Jewish and he was Italian. His mother Cynthia White, was an African American who had travelled to Italy from St Louis to work as a housekeeper for an American family and had married an Italian Jew, David Sinigaglia, from the Lombardy town of Mantova.

Alessandro had a long history of anti-fascist activity and had fought for the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. In August 1943, he became a leading member of the Communist-led resistance movement in Florence. In February 1944 he was captured and executed by a fascist militia.

Such was the esteem in which he was held by his fellow partisans that the first resistance brigade to enter Florence on its liberation on August 12, 1944 had named themselves after this black, Jewish Italian.

Fascism is once again on the march in Italy, with far right groups such as CasaPound and Forza Nuova growing in strength and number and racist attacks on the rise.

Many voters blame migrants and longer standing ethnic minorities for their own economic woes and stagnant social conditions, conveniently forgetting that generations of Italians once also crossed the seas in search of a better life.

In some quarters the nostalgia for a return to the days of Mussolini – something which has long bubbled beneath the surface of Italian political life – is now voiced openly.

Earlier this year, above a column by the Italian historian Andrea Mammone, of Royal Holloway, University of London, CNN’s website asked: ‘Can anything save Italy from a return to fascism?’

Those fears were compounded with the election in the spring of a government dominated by the right wing populist Lega and the ‘anti-establishment’ Five Star Movement, enjoying the support of Fratelli D’Italia (Brothers of Italy), the direct heirs to Mussolini’s Fascist Party.

‘Didn’t fascism end in 1945?,’ asked Mammone. ‘The truth is that in Europe – and not just in Italy – fascist ideologies never fully disappeared. They have also been able to survive because of post-war public amnesia.’

Or to put it another way, have Italians forgotten the spoon in their kitchen drawer?

Patrick Sawer is a senior reporter on the Daily and Sunday Telegraph