From its earliest days, Argentina has consistently failed to fulfil its immense potential. PAUL KNOTT suggests why, and sees few signs that a looming election will change anything

In the early 20th century, Argentina was one of the richest nations on earth and widely regarded as the country of the future. British politician and historian James Bryce said of it in 1912 that “all is modern and new; the prosperous present betokens a still more prosperous future. What limit can be set to the growth of its wealth and population?”

Argentina is still waiting for that golden future to arrive. The subsequent century has seen an endless loop of high hopes collapsing into hopeless crises. President Mauricio Macri was the latest to promise to break the dispiriting cycle following his victory in 2015. Sadly, serious economic difficulties are closing in again as Macri begins his campaign for re-election at the polls scheduled for October this year.

The history of modern Argentina began in the 1850s, when the sparsely populated nation enacted a constitution and opened itself up to immigration. By 1940, 6.6 million European migrants had flocked to the new land of opportunity, mostly Italians and Spaniards. Between the two world wars, the population of Buenos Aires alone quintupled to 2.5 million, making it the largest city in Latin America. They were attracted by the abundance of Argentina’s fertile land and the bright economic prospects of the expanding port city that was the gateway to the continent.

During this period, from the mid 19th century, education was expanded, telegraph lines were installed, rivers dredged, refrigerated ships acquired and roads and railways built in all directions. These developments opened up the ‘Pampas’ – the fertile lowlands covering much of the country – and other frontier lands, paving the way for massive growth in agricultural exports and overall commercial expansion.

Alas, these advances were squandered. A few hundred influential people greedily seized control of most of the land and economy. Their often-corrupt quest for ever more wealth prompted the country to borrow excessively at exorbitant interest rates, causing Argentina’s first – but far from last – debt crisis and economic crash in 1890. The currency, the peso, collapsed, prices for essential goods shot up and misery ensued for the masses.

A popular uprising ensued. It did not immediately succeed in overthrowing the oligarchy. But democracy finally arrived in 1916, with the relatively free and fair election of Radical Party leader Hipólito Yrigoyen. But this positive step was tempered by the political parties being run more as patronage machines than instruments for pursuing policies.

Nonetheless, Argentina began to prosper again, despite setbacks such as the bloody handling of a general strike in 1919. The neutral stance the country adopted in the First World War and increased demand in Europe for its products helped it to emerge as a creditor nation for the first time.

Culturally, too, Argentina thrived in the early decades of the 20th century and loosened its tendency to look back towards Europe for influences. Argentina’s famous footballing style and its own distinctive art forms began to emerge, such as the tango and the literature of writers including the father of magic realism, Jorge Luis Borges.

Yet again, the promise and prosperity did not last. The 1929 global economic crisis destroyed demand for Argentina’s exports. The impact was compounded by the Radical government’s inadequate responses.

Public unrest was followed in 1930 by a coup backed by a group of ultra-nationalist admirers of Mussolini. A cabal of military officers, oligarchs and elements of the senior clergy then took over the running of the country. The economic recovery they engineered brought some order to society and much comfort to the rich. But they neglected the struggling underpaid workers and, particularly under president Ramón Castillo (1940-43), squandered Argentina’s standing in the world by leaning towards the Axis powers of Germany, Italy and Japan in the Second World War.

This situation prompted a further coup in 1943 that deposed Castillo and set the stage for the entrance of Argentina’s most famous power couple, the charismatic Colonel Juan Domingo Péron and his young, actress companion María Eva Duarte Péron, better known as Evita. Péron astutely built his position as the standard bearer for the exploited farm and factory workers while minister of labour. A mass mobilisation of his supporters saw off an attempt by other military officers to usurp him and Péron took full control of the country following the 1946 election.

Once again, optimism surged through Argentina. Péron was the first president to enjoy genuine mass support. In this, he was more than matched by Evita, who inspired great devotion from the poor descamisados (‘the shirtless ones’), from whose ranks she had herself emerged.

The workers were rewarded with wages and rights on a scale they had never received before. Evita established a sprawling foundation which provided healthcare and social security, funded by leaning on businesses, unions and public bodies for donations.

Almost inevitably, it all fell apart again. Evita died of cancer in her early thirties in 1952, leading to mass mourning and depriving Péron of the connection she gave him to the masses. Péron’s programme of industrialisation, nationalisation and government control of agriculture failed. As the economy collapsed, business owners, parts of the armed forces and conservative Catholics opposed to Péron’s social reforms rebelled. Péron responded with ever greater repression but was eventually forced to resign in 1955 and flee into exile.

The subsequent decades saw Argentina slide ever deeper into military dictatorship, punctuated by a short return to power by Péron before his death in 1974. The military junta that seized control in 1976 was the worst Argentina has suffered. It was responsible for widespread torture and the ‘disappearance’ of an estimated 30,000 people during its so-called Dirty War against its opponents. The junta was finally deposed in the aftermath of its failed 1982 invasion of the Falkland Islands.

Since the 1980s restoration of democracy, the familiar story of boom, bust, debt and political mismanagement has resumed.

To some extent, this is the result of the legacy of Péronism that hangs over Argentina to this day. The exposure of Péron and Evita’s corruption never fully extinguished the more positive memories passed down through generations of descamisados. Their legend has inculcated an often unconscious belief in the power of individual leaders to sweep away problems at a stroke, even though in reality Péron achieved nothing of the sort.

The competition for political power continues to seesaw between those promising to bring about the Péronist dream, and those claiming to represent fiscally responsible pragmatism.

The most recent would-be heirs to the Pérons were Néstor Kirchner and his wife Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. Kirchner was president from 2003 to 2007, before handing over to Cristina. He died of a heart attack in 2010.

Yet again, their rule started promisingly. Initial progress was made in clearing up the economic problems they inherited. They boldly, too, reopened investigations into the crimes committed by the junta during the Dirty War, leading to over a thousand criminal convictions.

Almost inevitably, matters started to go downhill during Cristina’s second term. High taxes on farmers helped to kill the commodity boom upon which Argentina had been riding. As money ran short, the government worsened the situation by raiding the central bank and pension funds.

It also hid the true picture of its difficulties by fiddling the inflation figures. Meanwhile, insiders made fortunes from corruption. Cristina Fernández is herself currently on trial in the first of several graft cases.

The current president, Mauricio Macri, is the scion of a family of wealthy industrialists and former president of Boca Juniors, the football club at which Diego Maradona made his name.

Macri entered politics after suffering the ordeal of being kidnapped for 12 days by rogue police officers, being released only after his family is believed to have paid a multi-million-dollar ransom.

After eight years as governor of Buenos Aires, Macri won the presidency in 2015. He is not a member of either the Radical or Peronist family of traditional political parties. He promised a rupture with their shady political practices and clean, efficient government focused on economic stability.

Macri’s attempts to sort out the mess have largely failed. Over the past year, inflation has hit 50%, the peso has lost half of its value and average incomes are down by 10%. In a country that has had many grim experiences of international borrowing and the conditions attached, Macri has been forced to obtain a $57 billion IMF bailout.

None of this bodes well for Macri’s chances of re-election in October. Incredibly, his travails initially emboldened Cristina Fernández de Kirchner to launch a comeback as the opposition presidential candidate.

She soon recognised that she would be distracted by her various court cases and would struggle to attract support beyond her base of up to 30% of mostly poorer Argentines. For the moment, she has stepped down in favour of supporting a sometime ally, Alberto Fernández (no relation). Opinions vary on the extent to which Fernández is his own man or whether his strings are being pulled by Cristina.

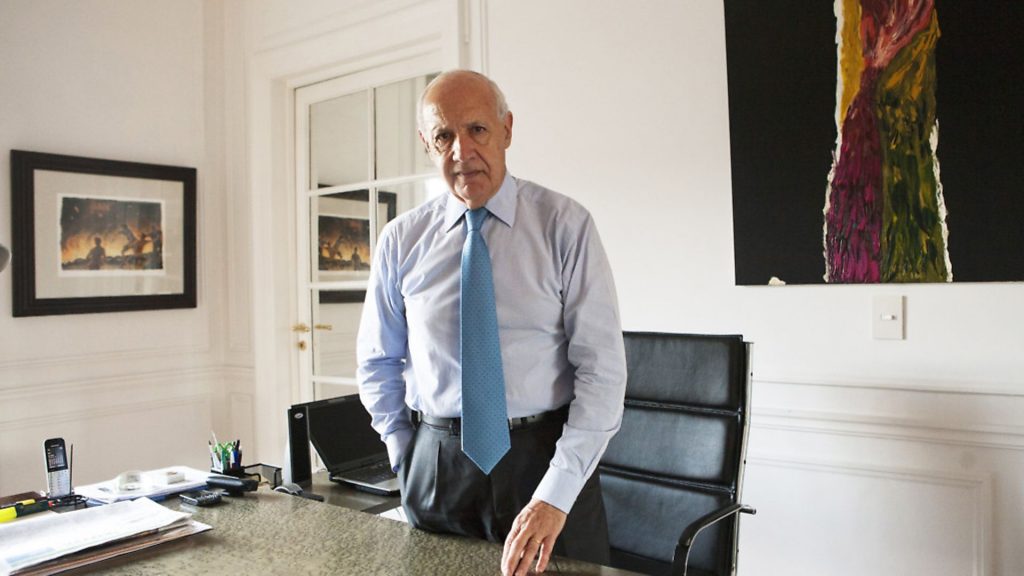

The picture is further complicated by the emergence of another candidate, respected former finance minister, Roberto Lavagna. Lavagna could come through to win in his own right or swing the race by opting to ally with either of the other two front-runners and committing to moderate their most radical instincts. Macri has also sprung an intriguing surprise by announcing a long-time ally of the Kirchners, Miguel Angel Pichetto, as his vice presidential running mate.

Whatever the electoral outcome in the autumn, Argentine’s hopes are no longer high for a rapid improvement in their circumstances any time soon.

The eternal question remains as to why a country with so many apparent assets and advantages still finds sustained success so elusive.

A pattern of poor governance and interventions by the armed forces, usually with disastrous consequences, provides much of the explanation. Underlying these repeated political failings are the multiple, deep divisions in Argentinian society between the overbearing metropolis of Buenos Aires and the provinces, the masses and the wealthy elite and clashing vested interests in industry, the military, agriculture and labour.

The repeated failures of governance have caused a widespread lack of respect for legitimate authority. This in turn compounds the problem by making the achievement of well-functioning public administration all the more difficult.

Perhaps the long-tarnished but still surviving myth of Argentina’s abundant assets plays a role too. The chimera of a glorious future eternally on the horizon inspires a faith in its inevitability, rather than the hard, consistent long-term work actually required to bring it about.

Modern Argentina: A timeline

1861

State of Buenos Aires reintegrated with Argentine Confederation to form united country

1880

Start of decades of liberal economic and immigration policies that lead to rapid income and population growth as well as progressive education and social policies

1908

Argentina has seventh highest per capita income in the world.

1912

Full adult male suffrage introduced.

1916

Hipolito Yrigoyen is elected president and introduces a minimum wage to counter the effects of inflation. Yrigoyen is elected again in 1928.

1930

Armed forces coup oust Yrigoyen amid sharp economic downturn caused by Great Depression. Civilian rule is restored in 1932, but economic decline continues

1942

Argentina, along with Chile, refuses to break diplomatic relations with Japan and Germany after the Japanese attack on the US Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbour

1943

Nationalist army officers seize power in protest at stagnation and electoral fraud. One leading figures is Colonel Juan Peron.

1945

Argentina declares war on Japan and Germany

1946

Peron wins presidential election on a promise of higher wages and social security. His wife – Eva, or Evita – is put in charge of labour relations.

1949

New constitution strengthens power of the president. Opponents are imprisoned, independent newspapers suppressed.

1951

Peron re-elected with a huge majority, but support begins to decline after Evita dies the following year.

1955

Violent military uprisings force Peron to resign and go into exile

1966

General Juan Carlos Ongania seizes power after years of unstable civilian government

1973

The Peronist party wins elections. Peron returns from exile and becomes president

1974

Peron dies and is succeeded by his wife, Isabel. Terrorism from right and left escalates, leaving hundreds dead amid strikes, protests and rampant inflation

1976

Armed forces seize power and launch ‘Dirty War’ in which thousands are killed on suspicion of left-wing sympathies

1978

Argentina win the World Cup, with the tournament held in the country

1982

Argentine forces occupy the Falkland Islands, which are later re-taken by a British task force

1983

Reeling from the Falklands fiasco, the junta restores democracy

1986

Captained by 25-year old Diego Maradona, Argentina wins the World Cup again

1989

Carlos Menem of the Peronist party is elected president and imposes economic austerity

1992

A new currency, the peso, is introduced and pegged to the US dollar

2001

The IMF stops $1.3bn in aid, banks shut down and at least 25 people die in rioting

2013

Argentina becomes first country to be censured by the IMF for not providing accurate data on inflation and economic growth. Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, of Buenos Aires, is chosen as Pope, and takes the name of Francis

2014

Argentina defaults on its international debt for the second time in 13 years