The dinosaurs vying for the Nigerian presidency offer little change but the election campaign does suggest a glimmer of hope for the country’s future.

Nigeria is Africa’s most populous country and its largest economy. It is home to a hardworking, creative and entrepreneurial population, but one which has long been held back by chronic maladministration.

The presidential and National Assembly elections, which are to be held on February 16, will not resolve the country’s substantial problems or lead to it realising its equally huge potential. But what happens next just might.

That somewhat free and fair elections are taking place at all in Nigeria represents progress. Since escaping colonial oppression, the country has been repeatedly blighted by conflict, corruption, coups and military dictatorships.

This month’s vote is likely to be the third credible democratic poll in a row, following 2011 and 2015. The latter elections saw an incumbent president, Goodluck Jonathan, defeated for the first time and a peaceful transition to Muhammadu Buhari.

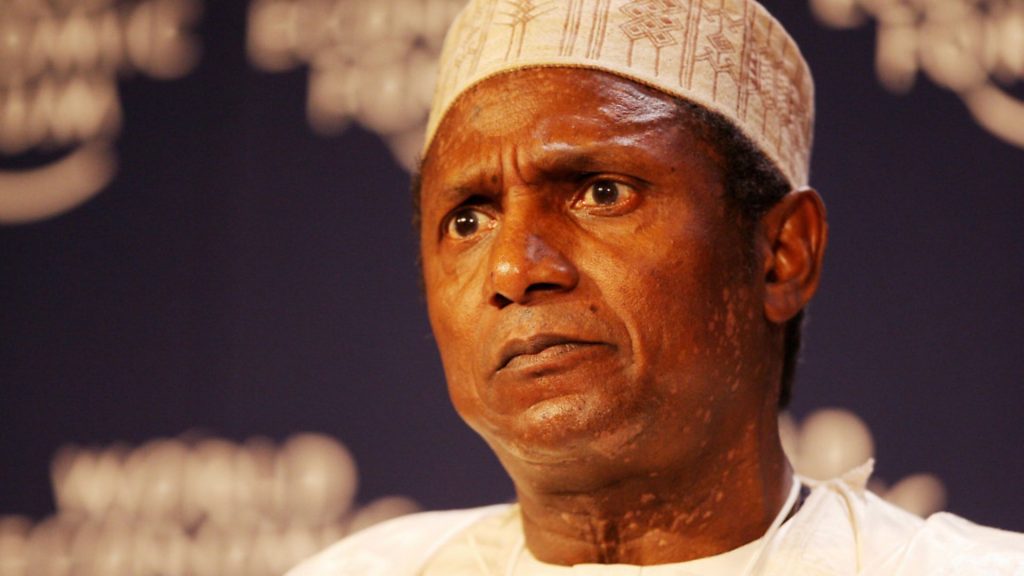

Despite his first term being disrupted by ill health, the 76-year-old Buhari, a former general, is running for re-election as the candidate of the All Progressives Congress (APC). His main opponent will be the 72-year old former vice president, Atiku Abubakar, of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP).

Neither leading candidate inspires much enthusiasm. While Buhari retains a reputation for personal probity, his record on tackling corruption, improving the economy and reducing insecurity is patchy. Atiku promises to address Nigeria’s dire youth unemployment and lift millions out of poverty. But his long history in politics – which has seen allegations of dubious business dealings made against him during his 1999-2007 vice presidential stint – raise doubts about him fulfilling his pledges. (Atiku dismissed the accusations against him and said they were politically motivated.)

This choice reflects the rut in which Nigerian politics has become stuck. The two main parties are almost indistinguishable ideologically and produce few concrete policy initiatives. Rather, as a recent report by the Chatham House think tank put it, they ‘function as patronage-fuelled coalitions of fractious elite networks that share one objective: to achieve political power and the financial rewards that come with it’.

Fortunately, there are signs that this dispiriting situation is beginning to change. The democratic habits instilled during several cycles of elections have shifted the political environment.

Public engagement is vigorous. Younger Nigerians, in particular, are starting to focus less on personalities and more on policies and how they relate to citizens’ lives. These new generations of voters are becoming accustomed to holding politicians accountable for their performance and less inclined to be fobbed off with trickle-down tokens of patronage.

The strongest signs of this shift are apparent in the slate of alternative candidates to the ‘big two’. The representatives of smaller parties are proving a more vibrant source of ideas to meet Nigeria’s needs.

Both leading candidates declined to participate in the main televised presidential debate, sparking further public criticism. But their absence made space for younger candidates such as the former deputy governor of the Central Bank, Kingsley Moghalu, and popular motivational speaker, Fela Durotoye, to articulate their plans.

The erstwhile leading female candidate Obiageli ‘Oby’ Ezekwesili, a former senior World Bank official and minister of education, was perhaps the most impressive of all. Throughout her career, Ezekwesili has been a formidable anti-corruption campaigner.

As a minister, she earned the nickname ‘Madame Due Process’ for her focus on sticking to the rules and good practice. Outside of government, her profile was further enhanced by her leadership of the ‘Bring Back Our Girls’ advocacy group. This organisation campaigned powerfully for the release of the Chibok schoolgirls abducted in 2014 by the brutal Boko Haram terrorist group in north eastern Nigeria.

Something of reluctant politician, Ezekwesili caused widespread disappointment by withdrawing from her quest for the presidency late in the campaign. She is now focused on trying to create an alliance between several of her former rivals, with the aim of consolidating votes and rallying support for a viable third alternative to Buhari and Atiku.

While some analysts do not entirely rule out the chances of a third-party shock, time is very short to reach an agreement between candidates and appeal to enough voters in a country as vast as Nigeria.

But Ezekwesili’s initiative does point the way forward to developing a strong ‘new generation’ candidate and campaigning machine for the next election.

The 2019 race between the two dinosaurs, Buhari and Atiku, is widely judged as being too close to call. Nigerian elections have usually been fought between candidates from the northern, mostly Muslim regions and the largely Christian south. This time, both men are Muslims from the same, northern Hausa-Fulani area, making the breakdown of their likely regional, ethnic and religious support hard to assess.

The advantages of incumbency may give Buhari a slight edge. Disturbingly, he has already pulled these levers by suspending the country’s top judge, Walter Onnoghen. A key part of chief justice Onnoghen’s role is to rule on electoral disputes and allegations of malpractice.

Should either Buhari or Atiku triumph, their four-year term is likely to see increasing public disgruntlement with the old political order. Buhari’s first stint saw an economic crisis worsened by Nigeria’s chronic over-reliance on oil sales and a fall in the global price for crude. This contributed to Nigeria overtaking India as the nation with the most people living in poverty in the world.

Nothing in either of the main candidates’ pitches or records suggests matters will improve with them in office. But democracy is getting Nigerians used to holding politicians to account based on their actions. This is opening the way for future candidates with the ideas to enable their dynamic nation to finally fulfil its immense potential.

A BLOODY HISTORY

Nigeria’s heads of state since independence – and their fates

Nnamdi Azikiwe (1963-1966)

The country’s first president; removed from office in a military coup

Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi (1966)

Senior military officer who seized power in the chaos of the coup which overthrew Azikiwe. Six months later, he was assassinated in a second coup, known as the Counter Coup

Yakubu Gowon (1966-1975)

Took power in the Counter Coup before being overthrown one nine years later. During his rule a civil war was fought in the country, to prevent the secession of Biafra

Murtala Mohammed (1975-1976)

A senior military officer who came to power in a coup before being assassinated in an abortive coup less than a year later

Olusegun Obasanjo (1976-1979)

A target in the attempted coup which saw Murtala Mohammed murdered, Obasanjo, a military officer, escaped assassination and helped thwart the plotters’ attempt to seize power. He ruled for three years before handing over to Shehu Shagari, becoming Nigeria’s first military head of state to transfer power peacefully to a civilian regime

Shehu Shagari (1979-1983)

Became president after winning an election. He ran for a second term in 1983 and won again. However, he was overthrown by major general Muhammadu Buhari (Nigeria’s current president)

Muhammadu Buhari (1983-1985)

Overthrown in a coup by general Ibrahim Babangida and other military officers

Ibrahim Babangida (1985-1993)

Promised to end military rule by 1990 (the year he was almost toppled in a failed coup). The date was pushed back to 1993, and elections were held that year. However, Babangida annulled the vote before the results were announced. Shortly afterwards, he resigned under pressure to cede control to a democratic government

Ernest Shonekan (1993)

A senior civilian official under Babangida, he took power in an interim government, which was intended to be a transitional administration. However, he was overthrown in a military coup after three months

Sani Abacha (1993-1998)

A senior army officer, he is, by some accounts, the most successful coup plotter in Nigerian history, having played roles in several, before he came to power himself in 1993. He died in office, with speculation that he was poisoned by prostitutes

Abdulsalami Abubakar (1998-1999)

Chief of the Defence Staff under Abacha, Abubakar assumed office after his death. Under his rule, a new constitution was adopted and, after elections, power was transferred to president-elect Obasanjo, who had ruled the country in the 1970s

Olusegun Obasanjo (1999-2007)

Became president after winning 62.6% of the vote. He was re-elected in a 2003 election, with observers citing ‘serious irregularities’. He stood down in 2007 amid controversy over an attempt to extend his time in office by another four years

Umaru Musa Yar’Adua (2007-2010)

Obasanjo’s chosen successor, he won a controversial election in 2007. He died in office three years later

Goodluck Jonathan (2010-2015)

Because of Yar’Adua’s fading health, Jonathan was appointed acting president in 2010 and was in the role when his predecessor died. He triumphed in an election in 2011 but lost in 2015, when he became the first Nigerian president to concede electoral defeat

Muhammadu Buhari (2015-)

Having played a role in coups in 1966, 1975 and 1983 (which took him to power), Buhari was voted into office in 2015. He is standing for a second term in elections this month