Polling expert PETER KELLNER on the long term factors behind the party’s decline, and what might help reverse it

Two rival theories have sought to explain Labour’s drubbing in this month’s elections. The left accuses Keir Starmer of deserting the party’s socialist principles. The leadership fears that the party has not changed enough: it needs to shed the ideological baggage that make it look elitist and metropolitan.

I believe both theories are wrong. They are too obsessed with the immediate past. In fact, the party’s crisis has been decades in the making. If the party is to recover, it needs to address its long-term troubles.

The biggest of these is the total transformation of its electoral base. Today’s typical Labour voter is no longer a blue-collar trade unionist working in a mine, shipyard, steelworks or factory. Instead s/he is a white collar, pro-European social liberal, living in or around a big city and working in health, education, finance, technology or public administration.

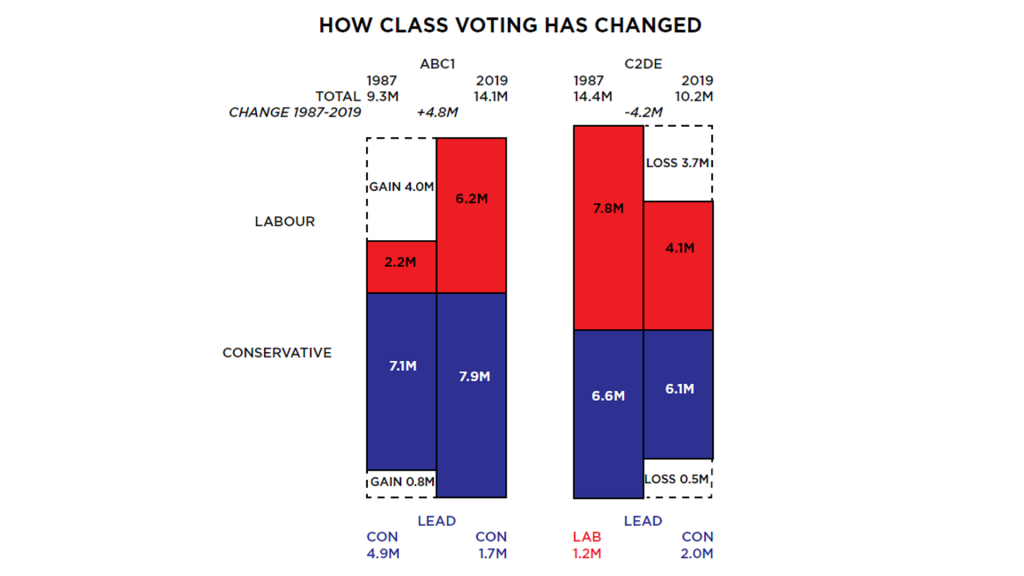

The chart on this page sets out the transformation of British society that lies at the root of Labour’s problems. It compares the 1987 and 2019 general elections. Their overall results were remarkably similar: a big majority based on a 12-point lead in the popular vote. That similarity helps us to explain what is happening today for it reveals the change in the structure of Labour’s support.

In 1987, almost four-fifths of Labour’s support came from working class, or C2DE, voters (7.8 million out of 10 million). By 2019, that number had almost halved, to 4.1 million. In contrast the number of its middle class voters almost trebled, from 2.2 to 6.2 million. These ABC1 voters comfortably outnumbered Labour’s C2DE support.

A large part of the reason is that there are millions more middle class and millions fewer working class voters than during the Thatcher era. However, if that were the sole explanation, one would expect similar changes in the structure of the Conservative vote. As the chart shows, this is not the case. In raw numbers, the changes have been much smaller: 500,000 fewer working class Tory voters, 800,000 more middle class voters.

This brings us to a point that is often overlooked in discussions of Labour’s problems. The Conservatives have always received around half their support from working class voters. (They included a fair number of trade union members, who joined in order to enjoy the benefits, not to advance the revolution).

The proportion of C2DE Tories has fluctuated a bit; but a moment’s thought shows the number must be large. Until the 1970s, more than two-thirds of all voters were working class. (In 1987, the base year for our chart, it was still 62%. It’s now 43%.) In the 1950s, the Tories won three successive elections with 48-49% of the total vote. They could not have done this without attracting millions of manual workers.

This brings us to the crucial point about working class voters. They have never been a homogenous block of eager socialists loyal to their trade union and the Labour Party. In broad terms, they have divided between collectivist and ‘instrumental’ voters – that is, between people committed to the long-term goals of socialism and solidarity, and those who cast their vote more pragmatically, for the party that they believe will do most to improve the lives and their families in the immediate future.

Those working in the mines, shipyards, steelworks, mills and factories were overwhelmingly collectivists: voting Labour was one way they expressed their beliefs. That’s why in the 1950s, Labour won seats such as Blyth, Don Valley, Bolsover and Ashfield with more than 70% of the vote. All those seats now have Tory MPs because the old, secure, well-paid, manual jobs have gone. As a result, the jobs and community organisations that nourished the collectivist identity of its base – such as working men’s clubs and active trade union branches – have shrunk or vanished.

Instead, instrumental voters have comprised a growing share of the dwindling pool of blue collar workers. Their party loyalties are driven by not by ideology but issues in their daily lives. Witness the popularity of council home sales in the 1980s. Today, the proportion of blue collar trade unionists with a collectivist outlook comprise only 2-3% of the electorate.

If anything, the mystery is not why Labour lost so many red wall seats at the last election, but why it didn’t lose them years earlier. One reason is that from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s, Tony Blair’s Labour Party attracted millions of instrumental, non-union working class voters with jobs in the private sector. But there is a second reason. Many voters stayed loyal to Labour even after their old jobs had gone. Call it habit, or nostalgia, or an identity that lingered after the mines, factories and so on had closed. Labour was losing ground steadily, but not catastrophically.

Looney Tunes cartoons provide the best demonstration of what has happened since. Wile E Coyote was renowned from being chased over a cliff edge. For a time, he continued to run horizontally without falling. Then gravity took over and suddenly pulled him down. Apply this to Labour’s two collapses in the past six years. In Scotland, the 2014 independence referendum caused gravity to kick in north of the border. In England’s ex-industrial heartlands, Brexit and Boris Johnson have had the same effect.

In Scotland, it is now clear that Labour’s lost votes have gone for good; at the very least, winning them back will be a slow and painful task. If I were a Labour strategist, I’d be terrified that the same is happening in the red wall seats. Last week’s election results, and not just in Hartlepool, deepen that terror.

What, then, can Labour do? Its first task is to secure its new base: the socially liberal, internationalist middle classes. Their support cannot be taken for granted. The Green Party is on the rise with its clear stance on Brexit and climate change. The votes it gained last week are ones that Labour should have won. So far the numbers aren’t huge; but with around 5% support in the polls, the Greens are already depriving Labour of votes it badly needs.

Worse for Labour, this switch might only have just begun. Look at Germany’s Greens. They are now vying with the Christian Democrats to be the largest party in this year’s election, having captured much of the country’s progressive middle class vote from the hapless SPD.

Britain’s first past the post voting system for Westminster makes it hard for small parties to break through. But the Greens (and Liberal Democrats – their revival at some point can’t be ruled out) can still hurt Labour. The danger for our centre left is that Labour will be squeezed relentlessly by a pincer movement that deprives it of both working class and middle class votes. It could remain too big to be replaced as a major party in parliament but too small to defeat the Conservatives.

However, firming up Labour’s middle class base, though vital, is not sufficient. Both sides of the pincer must be pushed back. The party also needs to win back working class voters; and, in hard numbers, this means appealing to an instrumental more than collectivist outlook. Hartlepool’s voters did not elect a Conservative MP because they want more socialism.

Labour’s real dilemma is that many of the causes that enthuse its new middle class base, such as Europe, overseas aid, LGBT rights and a fast transition to a carbon neutral future, are either anathema or irrelevant to many of the blue collar voters the party has lost.

What, then, can Labour do to maximise both its metropolitan and red wall appeal? I can’t see a quick fix. Instead, here’s a novel thought. Park that conundrum for the moment and start with a different question: What are the policies that will make Britain richer, fairer, cleaner and more contented? (I reckon they include reconnecting with the EU’s single market and customs union, not least because this would boost the prospects for red wall England; but that’s an argument for another day.)

Getting this right should improve lives in our struggling towns as well our thriving cities – and enhance Labour’s appeal in both. As Tony Blair’s landslide victories showed, instrumentalists and social liberals can vote the same way, despite their differences.

Britain’s more recent political history has dealt Keir Starmer a weak hand. He won’t escape the pincer by triangulating the rival identities that comprise Britain’s new electorate. He might just do by developing a brave and credible programme for the country’s future. Like a successful entrepreneur, he should start by getting the product right. When he’s done that, he can worry about how to sell it to his different target voters.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk