How did this Greek, Danish and German immigrant come to be lauded as the epitome of Britishness by many who most dislike immigration?

Had home secretary Priti Patel been around a century ago, we’d never have heard of Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh.

His father, Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark, may have been a terrific linguist, speaking Greek, Danish, German, French, English and Russian, but he never took an exam in his life. Qualifications, zero.

Andrew’s fluency in English would have scored him 10 of the required 70 points to qualify as skilled enough to work here. Stated exceptions for the officially pointless include “innovators, ministers of religion, sportspeople and artists”. Royalty doesn’t get a mention, and his love of yachting would be stretching the sports bit.

And the six months it takes to apply for the right to work in the UK would have presented issues to a guy who had just been court martialled and banished by the leaders of a military coup.

As for political asylum, forget it. In a post-Brexit UK, the Danish passports the family travelled on to escape Greece would count for nothing, except to rule them out for political asylum in the UK.

So had Patel had her way, young Fílippos, Prince of Greece and Denmark, would have seen out his baby years in the same orange crate in which he was smuggled into exile, stuck in some French hostel until his papa saved up enough to chance their luck across the Channel in a rubber dinghy. As 8,400 desperate people did in reality last year.

Of course, this is a ridiculous scenario. If Patel really could take a trip back in time to impose draconian immigration policies on Britain, she wouldn’t be here herself.

Her Ugandan-Indian parents, who set up a successful newsagent business after immigrating to the UK well before Idi Amin’s persecution of their countrymen in 1972, would have been turned back at the border by their own unborn home secretary daughter, like some smirky shouty Terminator, albeit less articulate than the Schwarzenegger version.

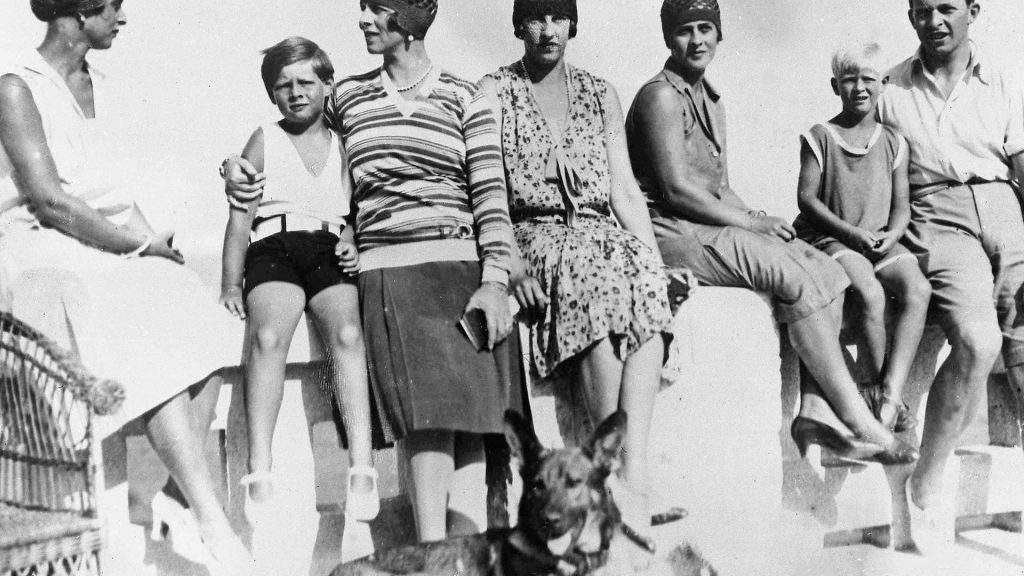

So Philip’s mum and dad were made welcome, sailing in on a gunboat sent by the King to rescue them, and little Philip grew up and married well, despite the wishes of the good old Queen Mum who had her suspicions and knew him as the Hun.

My own lifelong dislike of Prince Philip has nothing to do with my sketchy republicanism; he always struck me as particularly arrogant and offensive within a family who bow to nobody in those regards.

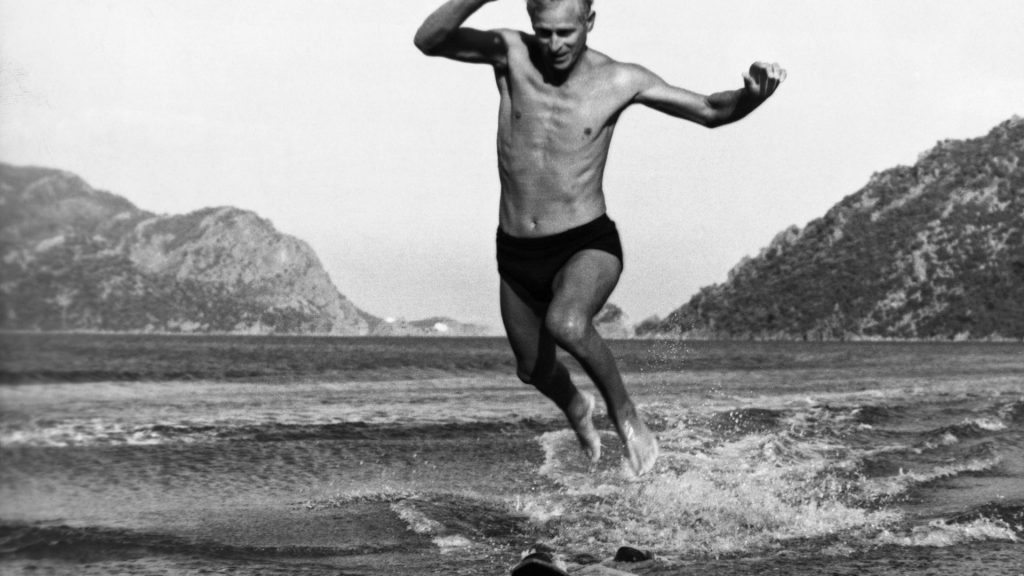

Admittedly, the last few days have severely dented that impression as a rounder, funnier, softer, more human human emerged. In truth, I’m about as interested in Prince Philip as I am in polo; I realise others find the whole thing engrossing, but even if I make it to 99, I doubt I’ll ever bother to understand why.

But something in his extraordinary journey into the bosom of this nation is fascinating: How does a Danish, German, Greek immigrant come to be lauded as the epitome of Britishness by the very people who are most likely to dislike immigration?

Statistically (and apologies if you defy the stats; few things are more infuriating than being mis-characterised by a YouGov poll) those aged 65+ are most likely to have a generally negative opinion of immigration in the UK; 46% versus 30% of those who think immigration is generally a good thing. At the other end of the adult spectrum, the 18-24 year olds, the numbers are reversed; 23% have a negative view of immigration and 42% a positive.

Since immigration was polled to be the second biggest issue for Leave voters in the Brexit referendum (behind ability to make our own laws) then no surprises that this attitude permeated that vote with 64% of those aged 65+ voting Leave, and 71% of those aged 18-24 voting Remain.

Curiously, and again few surprises here, it’s the same older generation who are most likely to have a more positive view of the monarchy; 70% believe it’s good for Britain compared to half that number, 35%, of 18-24s. (Interestingly, although the older group’s sentiment is relatively stable over time, there is massive volatility amongst the young. In just six months between July 2019 and January 2020, their positivity fell from 48% to 27%. During those months Prince Andrew gave an interview to the BBC. Say no more.)

So, we have an older generation who disproportionately dislike immigration yet disproportionately admire the immigrants ruling us.

Being ruled by immigrants is nothing new in Britain. Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, Normans, they all came and planted their flags on British soil. Others were less ambitious, but every bit as influential.

Flemish, Huguenots, Irish, Indians, Bangladeshis, Pakistanis, Eastern Europeans fleeing Nazis, Caribbeans, Nigerians, Kenyans, Chinese, Vietnamese, South Africans… hell, you only have to walk down a big city high street and look at the restaurants to know immigration isn’t just part of British identity. It is British identity.

We are, and have been since the time of Christ, a mongrel nation. You’d imagine those who’ve been around the longest would appreciate this the most, but as the stats above demonstrate, the opposite is true. Why?

Is it just new immigrants we object to? Is the abstract notion of immigration more threatening than the actual immigrants themselves? Does some sort of generational deference to authority explain older people’s admiration of the monarchy? And if so, does that apply more broadly, a tendency towards the comfort of stability rather than the risk of change? Unpicking these problems is a complex conundrum. In many ways it’s unhelpful to even try.

But if the adulation directed towards a man without one drop of British blood in his veins gives pause for thought about what, or rather who, really makes Britain great, then Philip’s life of national service will extend long beyond his death.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk